In previous posts, I highlighted a call for more prediction and accountability in the field of security studies, and detailed Trevor N. Dupuy’s forecasts for the 1990-1991 Gulf War. Today, I will look at The Dupuy Institute’s 1995 estimate of potential casualties in Operation JOINT ENDEAVOR, the U.S. contribution to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) peacekeeping effort in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On 1 November 1995, the leaders of the Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia, rump states left from the breakup of Yugoslavia, along with representatives from the United States, European Union, and Russia, convened in Dayton, Ohio to negotiate an end to a three-year civil war. The conference resulted from Operation DELIBERATE FORCE, a 21-day air campaign conducted by NATO in August and September against Bosnian Serb forces in Bosnia.

A key component of the negotiation involved deployment of a NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) to replace United Nations troops charged with keeping the peace between the warring factions. U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) and NATO had been evaluating potential military involvement in the former Yugoslavia since 1992, and U.S. Army planners started operational planning for a ground mission in Bosnia in August 1995. The Joint Chiefs of Staff alerted USEUCOM for a possible deployment to Bosnia on 2 November.[1]

Up to that point, U.S. President Bill Clinton had been reluctant to commit U.S. ground forces to the conflict and had not yet agreed to do so as part of the Dayton negotiations. As part of the planning process, Joint Staff planners contacted the Deputy Undersecretary of the Army for Operations Research for assistance in developing an estimate of potential U.S. casualties in a peacekeeping operation. The planners were told that no methodology existed for forecasting losses in such non-combat contingency operations.[2]

On the same day the Dayton negotiation began, the Joint Chiefs contracted The Dupuy Institute to use its historical expertise on combat casualties to produce an estimate within three weeks for likely losses in a commitment of 20,000 U.S. troops to a 12-month peacekeeping mission in Bosnia. Under the overall direction of Nicholas Krawciw (Major General, USA, ret.), then President of The Dupuy Institute, a two-track analytical effort began.

One line of effort analyzed the different phases of the mission and compiled list of potential lethal threats for each, including non-hostile accidents. Losses were forecasted using The Dupuy Institute’s combat model, the Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model (TNDM), and estimates of lethality and frequency for specific events. This analysis yielded a probabilistic range for possible casualties.

The second line of inquiry looked at data on 144 historical cases of counterinsurgency and peacekeeping operations compiled for a 1985 study by The Dupuy Institute’s predecessor, the Historical Evaluation and Research Organization (HERO), and other sources. Analysis of 90 of these cases, including all 38 United Nations peacekeeping operation to that date, yielded sufficient data to establish baseline estimates for casualties related to force size and duration.

Coincidentally and fortuitously, both lines of effort produced estimates that overlapped, reinforcing confidence in their validity. The Dupuy Institute delivered its forecast to the Joint Chiefs of Staff within two weeks. It estimated possible U.S. casualties for two scenarios, one a minimal deployment intended to limit risk, and the other for an extended year-long mission.

For the first scenario, The Dupuy Institute estimated 11 to 29 likely U.S. fatalities with a pessimistic potential for 17 to 42 fatalities. There was also the real possibility for a high-casualty event, such as a transport plane crash. For the 12-month deployment, The Dupuy Institute forecasted a 50% chance that U.S. killed from all causes would be below 17 (12 combat deaths and 5 non-combat fatalities) and a 90% chance that total U.S. fatalities would be below 25.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General John Shalikashvili carried The Dupuy Institute’s casualty estimate with him during the meeting in which President Clinton decided to commit U.S. forces to the peacekeeping mission. The participants at Dayton reached agreement on 17 November and an accord was signed on 14 December. Operation JOINT ENDEAVOR began on 2 December with 20,000 U.S. and 60,000 NATO troops moving into Bosnia to keep the peace. NATO’s commitment in Bosnia lasted until 2004 when European Union forces assumed responsibility for the mission.

There were six U.S. casualties from all causes and no combat deaths during JOINT ENDEAVOR.

NOTES

[1] Details of U.S. military involvement in Bosnia peacekeeping can be found in Robert F. Baumann, George W. Gawrych, Walter E. Kretchik, Armed Peacekeepers in Bosnia (Combat Fort Leavenworth, KS: Studies Institute Press, 2004); R. Cody Phillips, Bosnia-Herzegovina: The U.S. Army’s Role in Peace Enforcement Operations, 1995-2004 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 2005); Harold E. Raugh,. Jr., ed., Operation JOINT ENDEAVOR: V Corps in Bosnia-Herzogovina, 1995-1996: An Oral History (Fort Leavenworth, KS. : Combat Studies Institute Press, 2010).

[2] The Dupuy Instiute’s Bosnia casualty estimate is detailed in Christopher A. Lawrence, America’s Modern Wars: Understanding Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam (Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2015); and Christopher A. Lawrence, “How Military Historians Are Using Quantitative Analysis — And You Can Too,” History News Network, 15 March 2015.

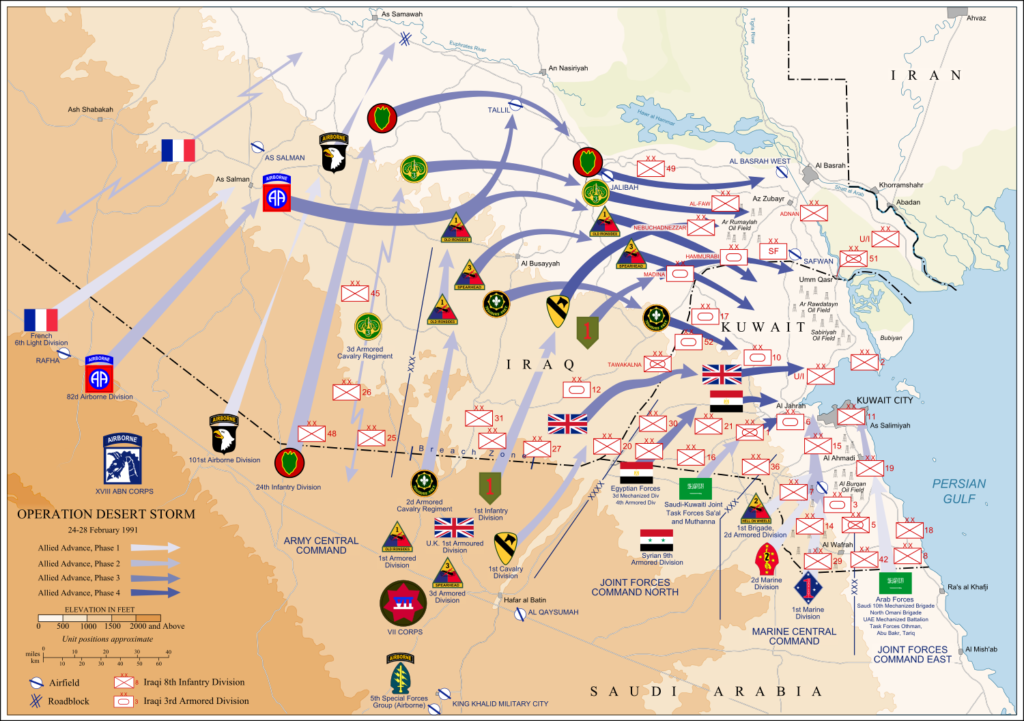

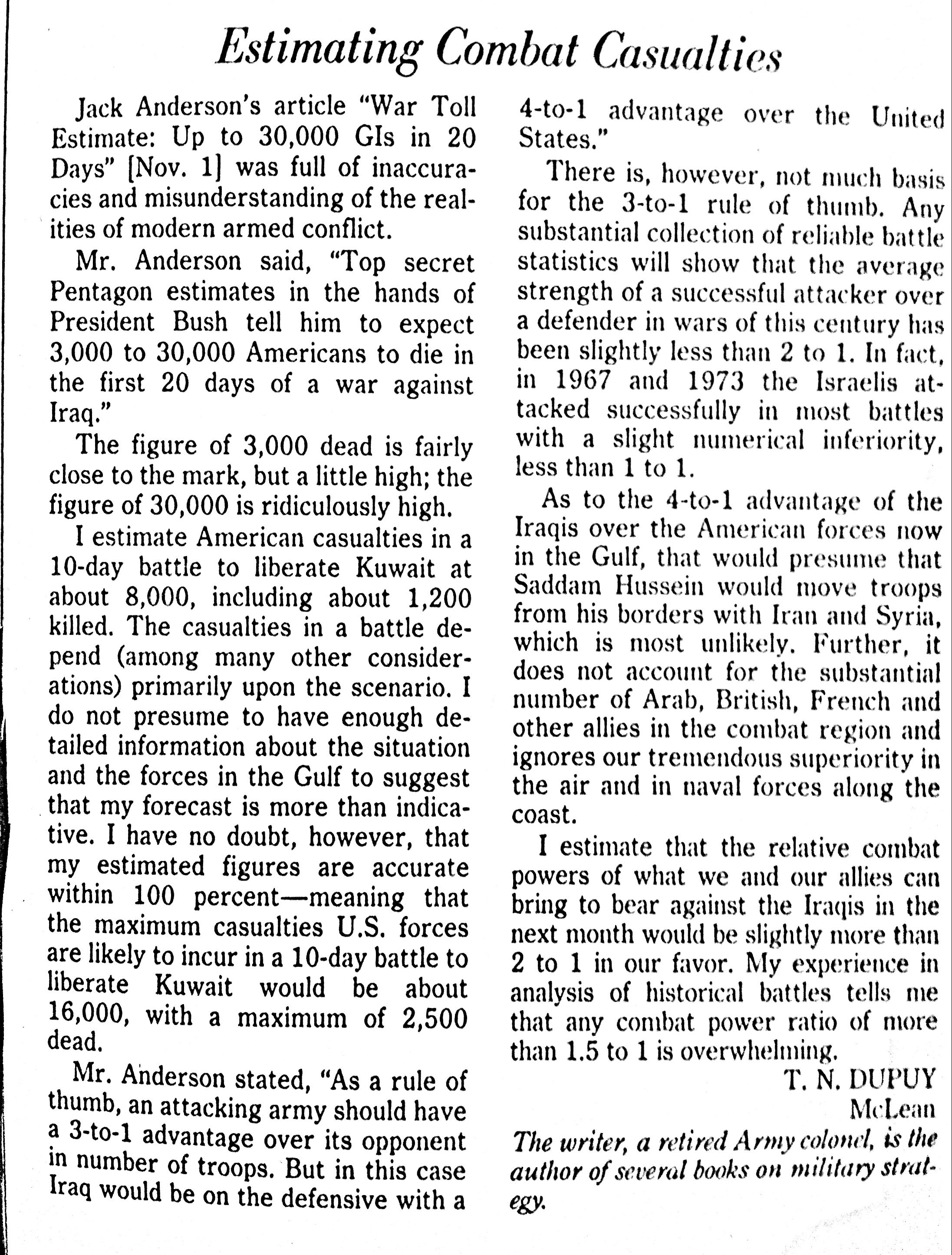

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.

A number of forecasts of potential U.S. casualties in a war to evict Iraqi forces from Kuwait appeared in the media in the autumn of 1990. The question of the human costs became a political issue for the administration of George H. W. Bush and influenced strategic and military decision-making.