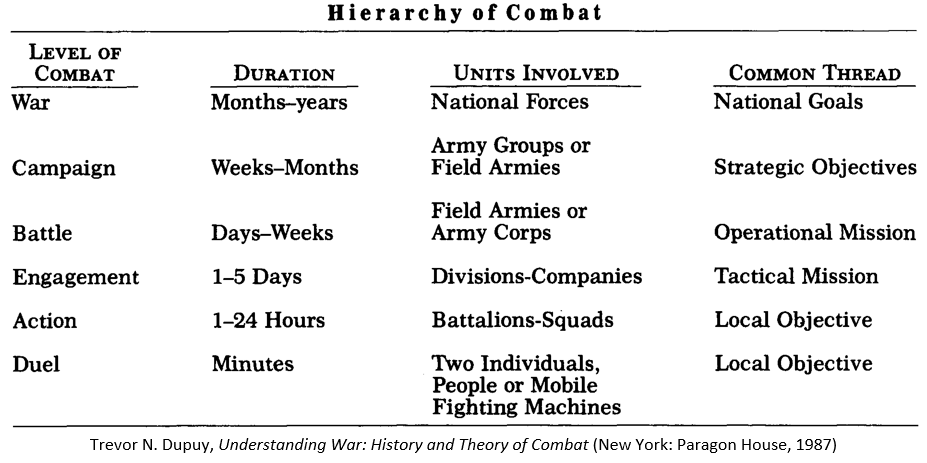

The second conceptual element in Trevor Dupuy’s theory of combat is his definition of the hierarchy of combat:

The second conceptual element in Trevor Dupuy’s theory of combat is his definition of the hierarchy of combat:

[F]ghting between armed forces—while always having the characteristics noted [in the definition of military combat], such as fear and planned violence—manifests itself in different fashions from different perspectives. In commonly accepted military terminology, there is a hierarchy of military combat, with war as its highest level, followed by campaign, battle, engagement, action, and duel.

A war is an armed conflict, or a state of belligerence, involving military combat between two factions, states, nations, or coalitions. Hostilities between the opponents may be initiated with or without a formal declaration by one or both parties that a state of war exists. A war is fought for particular political or economic purposes or reasons, or to resist an enemy’s efforts to impose domination. A war can be short, sometimes lasting a few days, but usually is lengthy, lasting for months, years, or even generations.

A campaign is a phase of a war involving a series of operations related in time and space and aimed toward achieving a single, specific, strategic objective or result in the war. A campaign may include a single battle, but more often it comprises a number of battles over a protracted period of time or a considerable distance, but within a single theater of operations or delimited area. A campaign may last only a few weeks, but usually lasts several months or even a year.

A battle is combat between major forces, each having opposing assigned or perceived operational missions, in which each side seeks to impose its will on the opponent by accomplishing its own mission, while preventing the opponent from achieving his. A battle starts when one side initiates mission-directed combat and ends when one side accomplishes its mission or when one or both sides fail to accomplish the mission(s). Battles are often parts of campaigns. Battles between large forces usually are made up of several engagements, and can last from a few days to several weeks. Naval battles tend to be short and—in modern times—decisive.

An engagement is combat between two forces, neither larger than a division nor smaller than a company, in which each has an assigned or perceived mission. An engagement begins when the attacking force initiates combat in pursuit of its mission and ends when the attacker has accomplished the mission, or ceases to try to accomplish the mission, or when one or both sides receive significant reinforcements, thus initiating a new engagement. An engagement is often part of a battle. An engagement normally lasts one or two days; it may be as brief as a few hours and is rarely longer than five days.

An action is combat between two forces, neither larger than a battalion nor smaller than a squad, in which each side has a tactical objective. An action begins when the attacking force initiates combat to gain its objective, and ends when the attacker wins the objective, or one or both forces withdraw, or both forces terminate combat. An action often is part of an engagement and sometimes is part of a battle. An action lasts for a few minutes or a few hours and never lasts more than one day.

A duel is combat between two individuals or between two mobile fighting machines, such as combat vehicles, combat helicopters, or combat aircraft, or between a mobile fighting machine and a counter-weapon. A duel begins when one side opens fire and ends when one side or both are unable to continue firing, or stop firing voluntarily. A duel is almost always part of an action. A duel lasts only a few minutes. [Dupuy, Understanding War, 64-66]

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces

Today’s edition of TDI Friday Read is a roundup of posts by TDI President Christopher Lawrence exploring the details of tank combat between German and Soviet forces