James Jay Carafano, historian and Vice President for Foreign and Defense Policy at the Heritage Foundation, recently issued a call for the U.S. defense community to back off debates over “the latest doctrinal flavor of the month” and return to a focus on the classic principles of war. “Most modern military doctrine should be scrapped,” Carafano wrote. “The Pentagon would be far better served if our military thinkers got back to the basics and taught the principles of war—and little more.”

James Jay Carafano, historian and Vice President for Foreign and Defense Policy at the Heritage Foundation, recently issued a call for the U.S. defense community to back off debates over “the latest doctrinal flavor of the month” and return to a focus on the classic principles of war. “Most modern military doctrine should be scrapped,” Carafano wrote. “The Pentagon would be far better served if our military thinkers got back to the basics and taught the principles of war—and little more.”

The principles of war are a list of basic concepts of warfare distilled from the writings of mostly Western military leaders and theorists that had become commonly accepted by the late 18th century, more or less. They vary in number depending on who’s list is consulted, but U.S. Army doctrine currently recognizes nine: Objective, Offensive, Mass, Economy of Force, Maneuver, Unity of Command, Security, Surprise, and Simplicity.

In 1987, Trevor N. Dupuy published what he termed “the timeless verities of combat.” These were a list of thirteen “unchanging operational features or concepts” based upon his previous twenty-five years of empirical research into a fundamental aspect of warfare, the nature of combat. He did not intend for these verities to substitute for the principles of war, but did believe that they were related to them. Dupuy asserted that the verities “describe certain fundamental and important aspects of warfare, which, despite constant changes in the implements of war, are almost unchanging because of war’s human component.”[1]

Trevor N. Dupuy’s Timeless Verities of Combat

- Offensive action is essential to positive combat results.

- Defensive strength is greater than offensive strength.

- Defensive posture is necessary when successful offense is impossible.

- Flank and rear attack is more likely to succeed than frontal attack.

- Initiative permits application of preponderant combat power.

- Defender’s chances of success are directly proportional to fortification strength.

- An attacker willing to pay the price can always penetrate the strongest defenses.

- Successful defense requires depth and reserves.

- Superior Combat Power Always Wins.

- Surprise substantially enhances combat power.

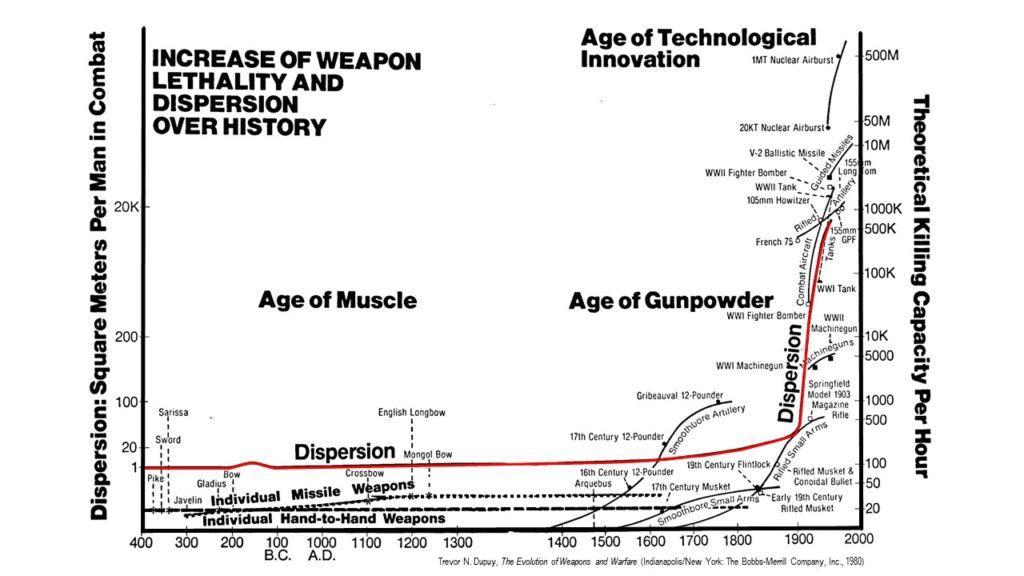

- Firepower kills, disrupts, suppresses, and causes dispersion.

- Combat activities are always slower, less productive, and less efficient than anticipated.

- Combat is too complex to be described in a single, simple aphorism.

Each of these concepts will be explored further in future posts.

NOTES

[1] Trevor N. Dupuy, Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (New York : Paragon House, 1987), pp. 1-8.

![Photo By United States Mint, Smithsonian Institution [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1804_dollar_type_I_obverse.jpeg.jpeg)