Given the historical trend toward battlefield dispersion as a result of the increasing lethality of weapons, how will the principle of mass apply in future warfare? I have been wondering about this for a while in the context of the two principle missions the U.S. Army must plan and prepare for, combined arms maneuver and wide area security. As multi-domain battle advocates contend, future combat will place a premium on smaller, faster, combat formations capable of massing large amounts of firepower. However, wide area security missions, such as stabilization and counterinsurgency, will continue to demand significant numbers of “boots on the ground,” the traditional definition of mass on the battlefield. These seemingly contradictory requirements are contributing to the Army’s ongoing “identity crisis” over future doctrine, training, and force structure in an era of budget austerity and unchanging global security responsibilities.

Over at the Australian Army Land Power Forum, Lieutenant Colonel James Davis addresses the question generating mass in combat in the context of the strategic challenges that army faces. He cites traditional responses by Western armies to this problem, “Regular and Reserve Force partnering through a standing force generation cycle, indigenous force partnering through deployed training teams and Reserve mobilisation to reconstitute and regenerate deployed units.”

Davis also mentions AirLand Battle and “blitzkrieg” as examples of tactical and operational approaches to limiting the ability of enemy forces to mass on the battlefield. To this he adds “more recent operational concepts, New Generation Warfare and Multi Domain Battle, [that] operate in the air, electromagnetic spectrum and cyber domain and to deny adversary close combat forces access to the battle zone.” These newer concepts use Cyber Electromagnetic Activities (CEMA), Information Operations, long range Joint Fires, and Robotic and Autonomous systems (RAS) to attack enemy efforts to mass.

The U.S. Army is moving rapidly to develop, integrate and deploy these capabilities. Yet, however effectively new doctrine and technology may influence mass in combined arms maneuver combat, it is harder to see how they can mitigate the need for manpower in wide area security missions. Some countries may have the strategic latitude to emphasize combined arms maneuver over wide area security, but the U.S. Army cannot afford to do so in the current security environment. Although conflicts emphasizing combined arms maneuver may present the most dangerous security challenge to the U.S., contingencies involving wide area security are far more likely.

How this may be resolved is an open question at this point in time. It is also a demonstration as to how tactical and operational considerations influence strategic options.

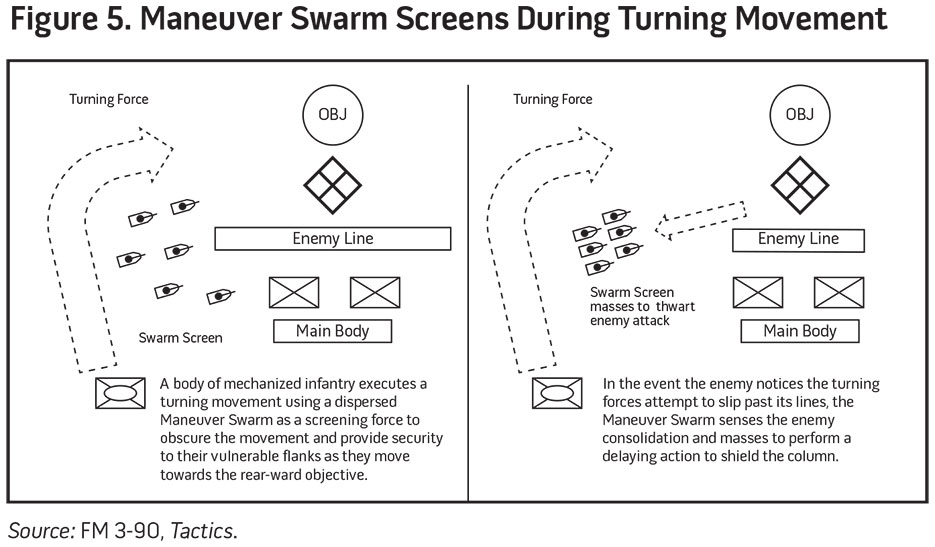

For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in

For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its

The U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command has released a revised draft version of its