[This post is based on “Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal,” by H. W. Beuttel, originally published in the December 1997 edition of the International TNDM Newsletter.]

Posts in this series:

Iranian Casualties in the Iran-Iraq War: A Reappraisal

Iranian Missing In Action From The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

The “Missing” Iranian Prisoners of War From The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Killed And Died Of Wounds In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Wounded In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Chemical Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

Iranian Civil Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

A Summary Estimate Of Iranian Casualties In The Iran-Iraq War

The Iran-Iraq War was the longest sustained conventional war of the 20th Century. Lasting from 22 September 1980 to 20 August 1988, the seven years, ten months, and twenty-nine days of this conflict are some of the least understood in modem military history. The War of Sacred Defense to the Iranians and War of Second Qadissiya to Iraqis is the true “forgotten war” of our times. Seemingly never ending combat on a scale not witnessed since World War I and World War II was the norm. Casualties were popularly held to be enormous and, coupled with the lack of battlefield resolution year after year, led to frequent comparisons with the Western Front of World War I. Despite the fact that Iran had been the victim of naked Iraqi aggression, it was the Iraqis who were viewed as the “good guys” and actively supported by most nations in the world as well as the world press.

Studying the Iran-Iraq War is beset with difficulties. Much of the reporting done on the war was conducted in a slipshod manner. Both Iraq and Iran tended to exaggerate each other’s losses. As oftentimes Iraqi claims were the only source, accounts of Iranian losses became exaggerated. The data is highly fragmentary, often contradictory, usually vague in particulars, and often suspect as a whole. It defies complete reconciliation or adjudication in a quantitative sense as will be evident below.

There are few stand-alone good sources for the Iran-Iraq War in English. One of the first, and best, is Edgar O’Ballance, The Gulf War (1988). O’Ballance was a dedicated and knowledgeable military reporter who had covered many conflicts throughout the world. Unfortunately his book ends with the Karbala-9 offensive of April 1987. Another good reference is Dilip Hiro, The Longest War: The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict (1990). Hiro too is a careful journalist who specializes in South Asian affairs. Finally, there is Anthony Cordesman and Abraham Wagner, The Lessons of Modern War Volume III: The Iran-Iraq War (1990). This is the most comprehensive treatment of the conflict from a military standpoint and tends to be the “standard” reference. Finally there are Iranian sources, most notably articles appearing since the war in the Tehran Times, Iran News, the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) and others.

This paper will approach the subject of losses in the conflict from the Iranian perspective. This is for two reasons. First, too often during the war Iraqi claims and figures were uncritically accepted out of prejudice against Iran. Secondly, since the War the Iranians have been more forthcoming about details of the conflict and though not providing direct figures, have released related quantified data that allows us to extrapolate better estimates. The first installment of this paper examines the evidence for total Iranian war casualties being far lower than popularly believed. It will also analyze this data to establish overall killed-to-wounded ratios, MIA and PoW issues, and the effectiveness of chemical warfare in the conflict. Later installments will analyze selected Iranian operations during the war to establish data such as average loss rate per day, mean length of engagements, advance rates, dispersion factors, casualty thresholds affecting breakpoint and other issues.

Casualties as Reported and Estimated

Too often incorrect formulae were applied to calculate casualties or the killed-to-wounded ratio. The standard belief was that Iran suffered two wounded for every killed—a ratio not seen since the ancient world. Colonel Trevor N. Dupuy established that the average distribution of killed-to-wounded in 20th Century warfare is on the order of 1:4 and in fact this relationship may be as old as the year 1700.[1] In Operation Peace for Galilee of 1982 the Israeli ratio of killed-to-wounded was on the order of 1:6.5 while the Syrian was 1:3.56.[2] At the same time in the Falklands, U.K. casualty ratio was 1:3. For Argentine ground forces it was 1:4.85.[3] Also it was assumed that Iran must have suffered 3-4 times the casualties of Iraqi forces in many given engagements on the basis of no good evidence this author can find.

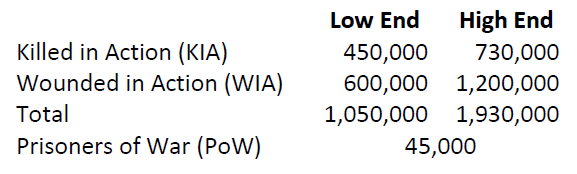

Typical Western estimates of Iranian losses in the war are given below.[4]

The lowest estimate of Iranian KIA was from the Pentagon which estimated the killed (military and civilian) at 262,000.[5]

At the end of 1980 the Iraqis claimed 4,500 Iranian KIA and 11,500 WIA.[6] Iraqi claims as of 22 September 1981 were 41,779 Iranian KIA[7] By the end of August 1981 other estimates placed it as 14,000-18,000 KIA and some 26,000-30,000 WIA.[8] Alternate estimates placed this at 14,000 KIA and 28,000 WIA,[9] Still others claimed 38,000 KIA.[10] During the first half of 1982 estimate was 90,000 Iranians killed.[11] Iran’s casualties in its 1984 offensives resulted in 30,000-50,000 more KIA.[12] In mid-1984 Iran’s KIA were 180,000-500,000 and WIA 500,000-825,000.[13] By 23 March 1985, Iranian KIA may have been 650,000 with 490,000 “seriously” wounded.[14] In September 1986 the count of Iranian dead was 240,000.[15] By April 1987 Iran had 600,000-700,000 KIA and twice that number wounded.[16] Iraq claimed 800,000 total Iranian KIA at the time of the cease-fire.[17] Figure 1 graphically depicts this reporting.

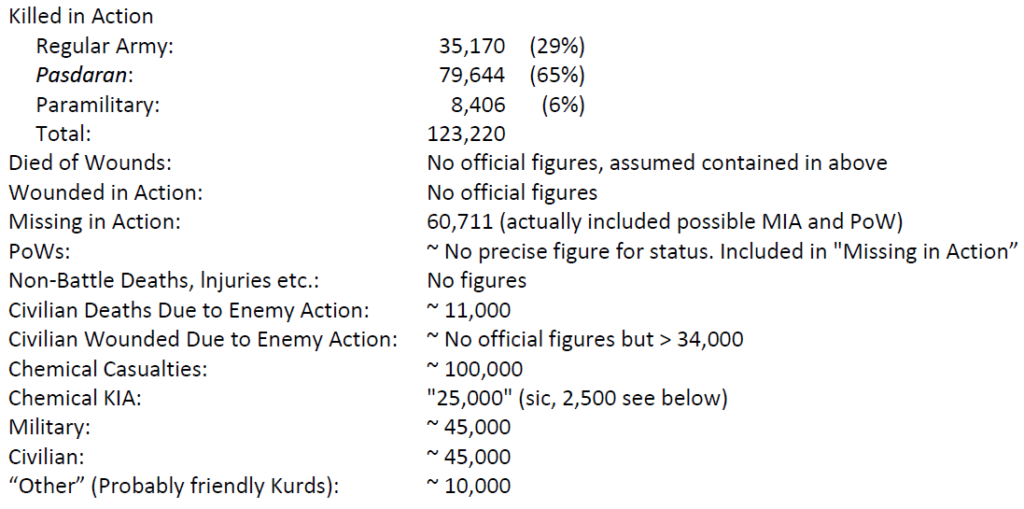

Official Iranian statistics released on 19 September 1988 immediately after the cease fire listed the following casualty figures:

Official Iranian statistics released on 19 September 1988 immediately after the cease fire listed the following casualty figures:

Mr Beuttel, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, was employed as a military analyst by Boeing Research & Development at the time of original publication. The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of The Boeing Company.

Mr Beuttel, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, was employed as a military analyst by Boeing Research & Development at the time of original publication. The views and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of The Boeing Company.