As the United States’ ongoing decade and a half long involvement in Afghanistan remains largely recessed from the public mind, the once-intense debate over counterinsurgency warfare has cooled as well. Interest stirred mildly recently as the Trump administration rejected a proposal to turn the war over to contractors and elected to slightly increase the U.S. troop presence there. The administration’s stated policy does not appear to differ significantly from that that proceeded it.

The public debate, such as it was, occasioned two excellent articles addressing Afghanistan policy and relevant recent academic scholarship on counterinsurgency, one by Max Fisher and Amanda Taub in the New York Times, and the other by Patrick Burke in War is Boring.

Fisher and Taub addressed the question of the seeming intractability of the Afghan war. “There is a reason that Afghanistan’s conflict, then and now, so defies solutions,” they wrote. “Its combination of state collapse, civil conflict, ethnic disintegration and multisided intervention has locked it in a self-perpetuating cycle that may be simply beyond outside resolution.”

The article weaves together findings of studies on these topics by Ken Menkhaus; Romain Malejacq; Dipali Mukhopadhyay; and Jason Lyall, Graeme Blair, and Kosuke Imai. Fisher and Taub concluded on the pessimistic note that bringing peace and stability to Afghanistan may be on a generational time scale.

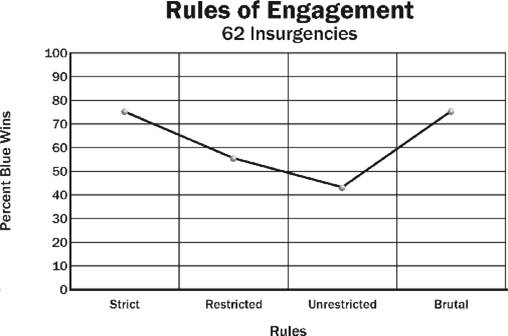

Burke looked at a more specific aspect of counterinsurgency, the relationship between civilian casualties and counterinsurgent success of failure. Separating insurgents from the civilian population is one of the central conundrums of counterinsurgency, referred to as the “identification problem.” Burke noted that the current U.S. military doctrine holds that “excessive civilian casualties will cripple counterinsurgency operations, possibly to the point of failure.” This notion rests on the prevailing assumption that civilians have agency, that they can choose between supporting insurgents or counterinsurgents, and that reducing civilian deaths and “winning hearts and minds” is the path to counterinsurgency success.

Burke surveyed work by Matthew Adam Kocher, Thomas B Pepinsky, and Stathis N. Kalyvas; Luke Condra and Jacob Shapiro; Lyall, Blair and Imai, Christopher Day and William Reno; Lee J.M. Seymour; Paul Staniland; and Fotini Christia. The picture portrayed in this research indicates that there is no clear, direct relationship between civilian casualties and counterinsurgent success. While civilians do hold non-combatant deaths against counterinsurgents, the relevance of blame can depend greatly on whether the losses were inflicted by locals for foreigners. In some cases, counterinsurgent brutality helped them succeed or had little influence on the outcome. In others, decisions made by insurgent leaders had more influence over civilian choices than civilian casualties.

While the collective conclusions of the studies surveyed by Fisher, Taub and Burke proved inconclusive, the results certainly warrant deep reconsideration of the central assumptions underpinning prevailing U.S. political and military thinking about counterinsurgency. The articles and studies cited above provide plenty of food for thought.