We are looking at a rather extended series of protests in Venezuela now. Sometimes the successful street protests or people power protests that overthrow governments are fairly brief and sudden. For example, the street protests that ended the attempted coup, saved Boris Yeltsin as president of Russia, and eventually resulted in the dissolution of the 74-year old Soviet Union lasted only 3 days and resulted in only 3 deaths. Many other of the people power protests in Eastern Europe in 1990/1991 were also brief and not very bloody.

But often these things last a little longer with a lot more blood shed. For example, the Romanian protests of 1991 lasted 12 days, and involved considerable violence, with snipers firing on the protesting crowds as foreign (Libyan) soldiers tried to protect the regime. When it was done 689 to 1,290 people were dead but the government was overthrown (and executed). The more recent “successful” street protests that overthrew the 29-year Egyptian government of Mubarak in 2011 lasted 17 days. Some 846 people died in the violence during the protests. One of the more extended efforts, conducted in the freezing winter of Ukraine, and also under sniper fire, was the Euromaiden Protests of 2013/2014 that lasted a little more than three months. When it was done, the government of Yanukovych was overthrown (for a second time), but at a cost of 104-780 people’s lives, and the loss of territory due to political protests and seizure by Russia. On the other hand, there is the Tiananmen Square protests on 1989, which went on for about a month and half before the government sent in the tanks. This failed protest cost at least 1,045 lives, and some claim thousands.

Now, we have never done a survey of people power protests and attempts to remove governments by protest. This would be useful. I do not know if longer protests have a higher or lower success rate than shorter protests. Right now we are looking at the most recent round of protests in Venezuela that started on 10 January 2019 and that have now gone on for four+ months. One could make the claim that the protests started in 2017 or 2014. They have also been bloody with at least 107 people killed in 2019.

The question is, as these protests extend, does this mean that Maduro has a greater chance of hanging on to power? This may be the lesson of Syria, which started as a series of protests in March 2011 that then morphed into a bloody civil war (over 200,000 dead) that is still going on today.

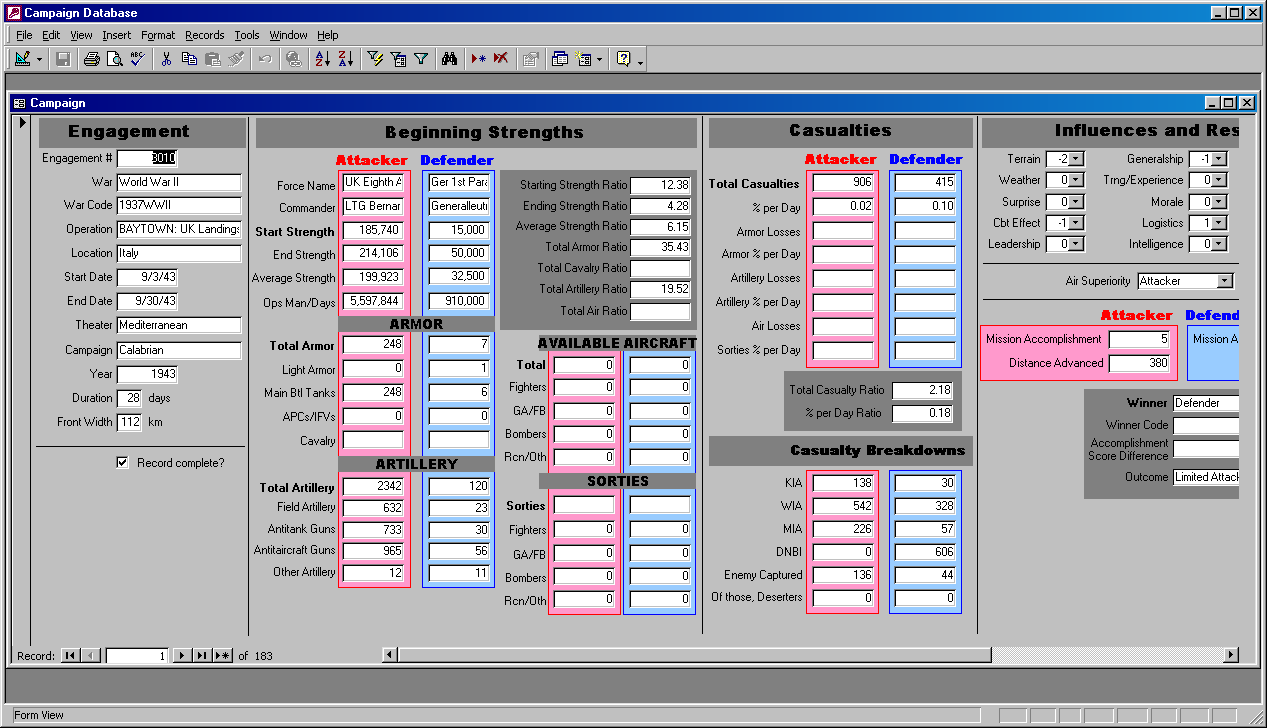

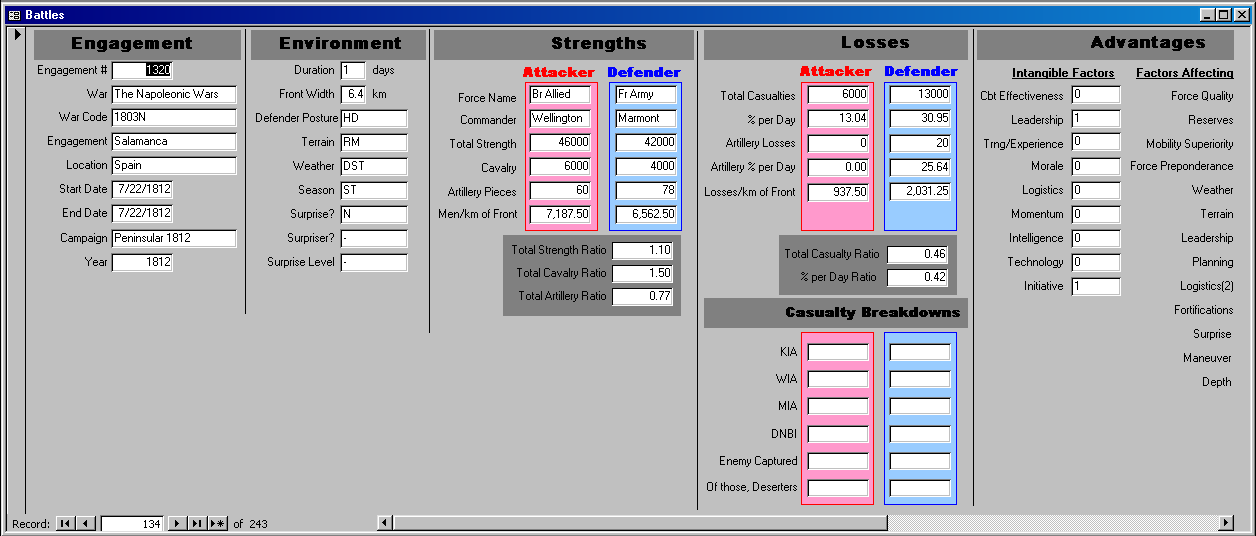

I would be sorely tempted to assemble a data base of people power protests since WWII (which is not a small effort) and then see if I could find some patterns there (like we did in our insurgency studies), including success rate, duration, size, and the reasons for successful versus unsuccessful protests.