Continuing the discussion on Afghanistan drawn from fragments of text from pages 264-266 of America’s Modern Wars.

LESSONS AND OBSERVATIONS

There are five final lessons or observations that we wish to make about this war [Afghanistan]…

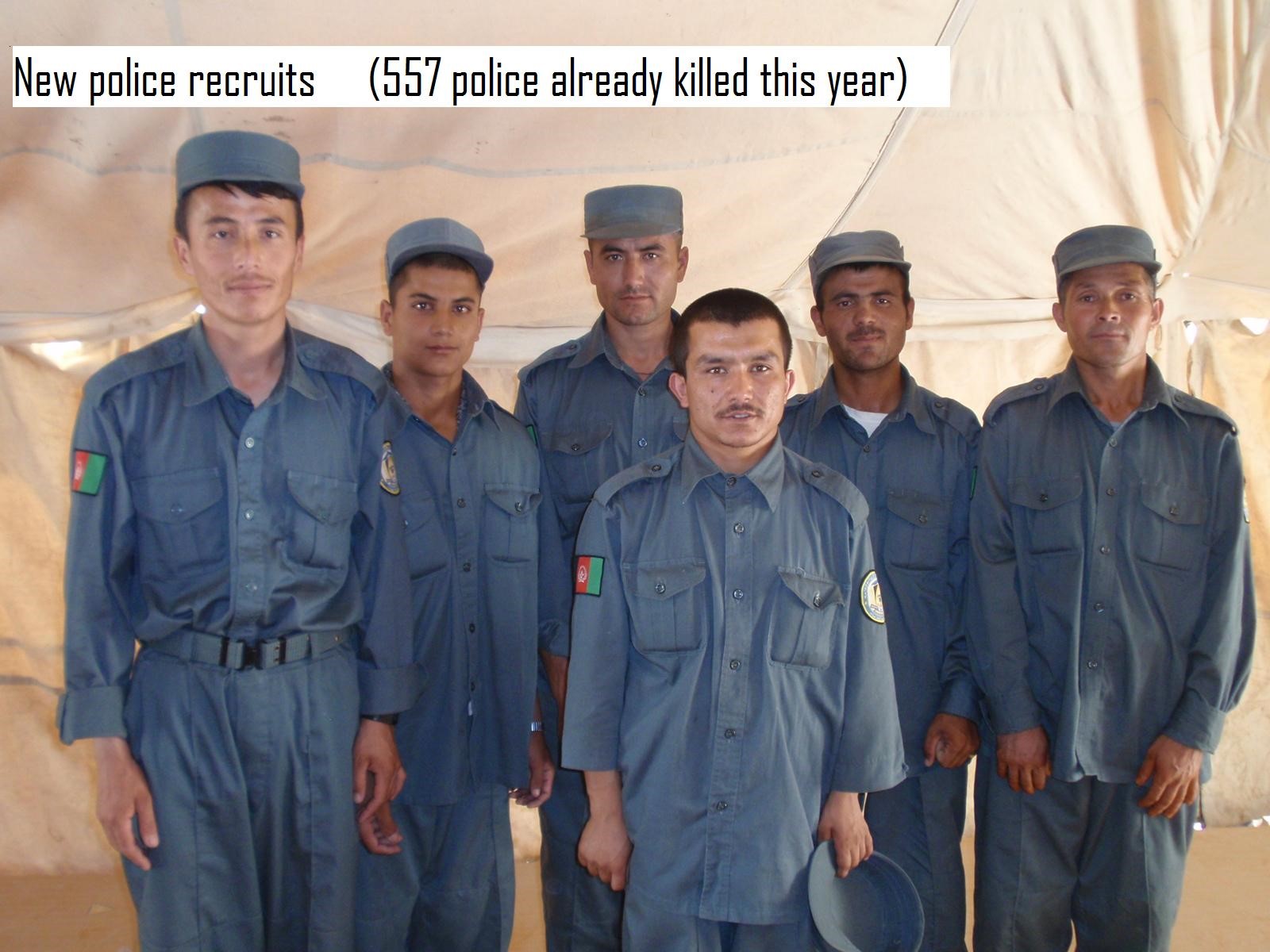

Second, we question the wisdom of concentrating and giving priority to developing the Afghan police forces ahead of the Afghan army. Some of this appears to have been inspired by the British example of counterinsurgencies, which leaned heavily on using police as part of its counterinsurgent forces. This worked in part because they also had sufficient ground troops (usually 25-to-1 or greater ratios) and were facing very small insurgencies. When we did our analysis of insurgencies, including the logit regression model, we did not count police forces in the counterinsurgent forces in the data or the model. We felt that most police were not dedicated to the task of counterinsurgency most of the time and had many other duties and tasks to perform. As such, we did not count the traffic cops in Saigon as part of the war effort against the Viet Cong. Now, if there were portions of the police force clearly set aside with a primarily counterinsurgency mission, we did count those, but in most of our cases, we did not include them in our data and our calculations.

As such, we did not include them in our analysis of Afghanistan, and we still believe that this is the best representation. But, the U.S. by focusing on building up the Afghan police, and there were more Afghan police than army from 2004 through 2006, probably did not provide the government with the tools it needed to secure the country side. Isolated police stations simply do not establish government control. As such, we believe that the U.S. learned the wrong lessons from its review of UK counterinsurgency doctrine because they did not properly and fully understand the context in which they were conducted: which was with the UK having overwhelming military force. We therefore tried to substitute police for army. We also did the same thing early in Iraq also.

….

(to be continued)