Shawn posted a very nice summary a couple of days ago. It is worth reading if you have not already: Meanwhile in Afghanistan

Recent article reports the same trends: Afghan-government-lost-2-percent-territory

A couple of things get my attention in all this:

- They are talking about control of territory. I believe control of population is a lot better metric.

- One notes in Shawn’s write up that control of population is 68.5% (vice 61.3% of area).

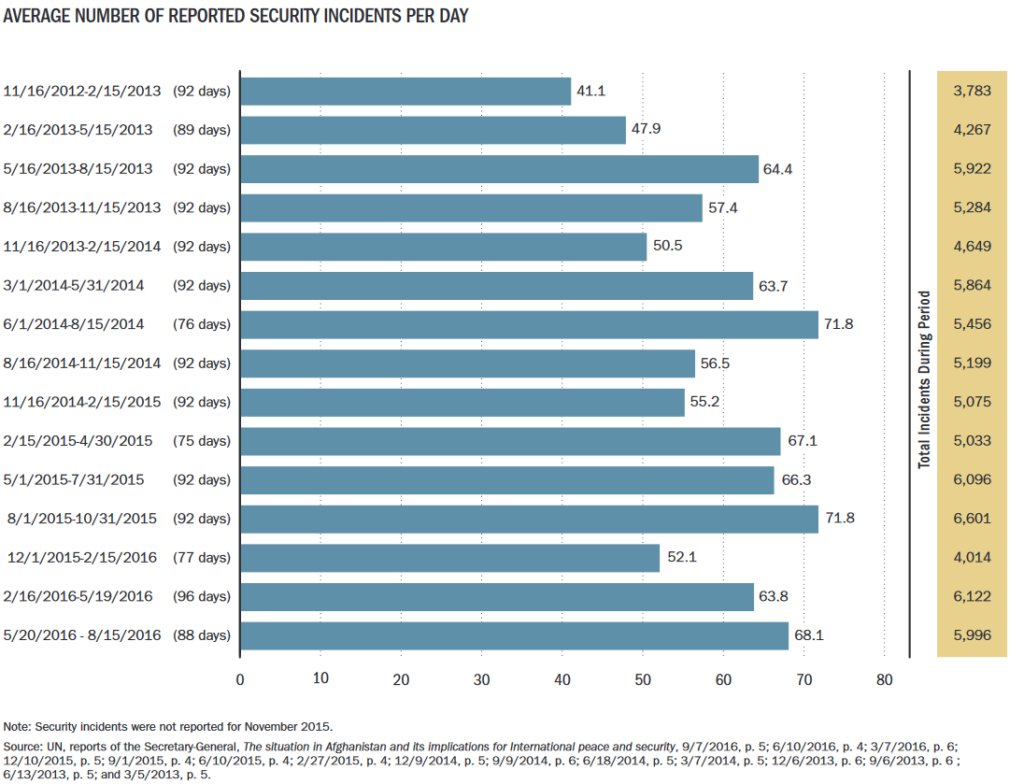

- The insurgent level of activity is very high:

- 5,523 Afghan Army and police killed (15,000 casualties)

- 22,733 incidents from 8/1/2015 to 8/15/2016

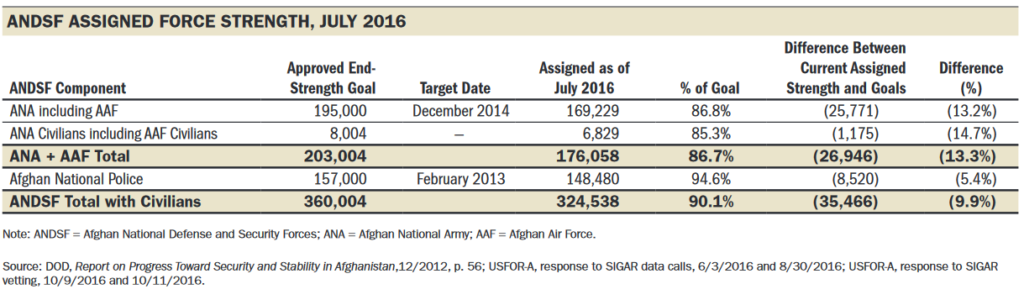

Based on Chapter 11 (Estimating Insurgent Force Size) of my book America’s Modern Wars, working backward from this incident data would mean that there are something like 60,000 – 80,000 full-time and part-time insurgents operating. There is a lot comparing apples to oranges to get there: for example, how are they counting incidents in Afghanistan vice how were they counting incidents in the past cases we use for this estimate, what is the mix of full-time and part-time insurgents, how active and motivated are the insurgents, and so forth; but that level of activity is similar to the level of activity in Iraq at its worse (26,033 incidents in 2005, 45,330 in 2006 and 19,125 in 2007 according to one count). We had over 180,000 U.S. and coalition troops there to deal with that. The Afghani’s have 170,000 Army and Air Force or around 320,000 if you count police (and we did not count police in our database unless there were actively involved in counterinsurgent work). The 5,500+ Afghan Army and police killed a year indicates a pretty active insurgency. We lost less than 5,500 for the entire time we were in Iraq. The low wounded-to-killed ratio in the current Afghan data may well be influenced by who they choose to report as wounded and how they address lightly wounded (as discussed in Chapter 15, Casualties, in my upcoming book War by Numbers). Don’t know what current U.S. Army estimates are of Afghan insurgent strength.

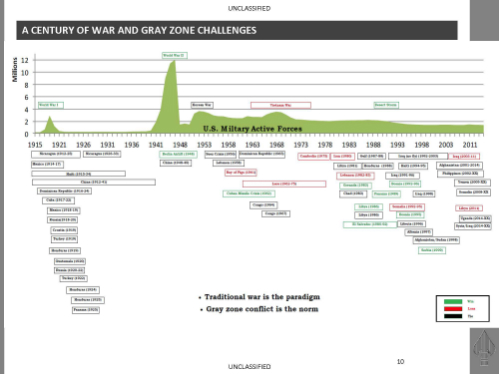

Now, in Chapter Six of my book America’s Modern Wars, we developed a force ratio model based upon 83 historical cases (see chart at top of this post). It was very dependent on the cause of the insurgency, whether it was based on a central idea (like nationalism) or was regional or factional, or whether it was based on a overarching idea (like communism). I don’t still don’t really know the nature of the Afghan insurgency, and we were never funded to study this insurgency (we were only funded for Iraq work). So, I have not done the in-depth analysis of the Afghan insurgency that I did for Iraq. But…….nothing here looks particularly positive.

We never did an analysis of stalemated insurgencies. It could be done, although there are not that many cases of these. One could certainly examine any insurgency that lasts more than 15 years for this purpose. Does a long stalemated insurgency mean that the government (or counterinsurgents) eventually win? Or does a long stalemated insurgency mean that the insurgents eventually win? I don’t know. I would have to go back through our database of 100+ cases, update the data, sort out the cases and then I could make some predictions. That takes time and effort, and right now my effort is focused elsewhere. Is anyone inside DOD doing this type of analysis? I doubt it. Apparently a stalemate means that you can now pass the problem onto the next administration. While it solves the immediate political problem, is really does not answer the question of whether we are winning or losing. Is what we are doing good enough that this will revolve in our favor in the next ten years, or do we need to do more? I think this is the question that needs to be addressed.