With the emergence of the importance of cross-domain fires in the U.S. effort to craft a joint doctrine for multi-domain operations, there is an old military concept to which developers should give greater consideration: interchangeability of fire.

This is an idea that British theorist Richard Simpkin traced back to 19th century Russian military thinking, which referred to it then as the interchangeability of shell and bayonet. Put simply, it was the view that artillery fire and infantry shock had equivalent and complimentary effects against enemy troops and could be substituted for one another as circumstances dictated on the battlefield.

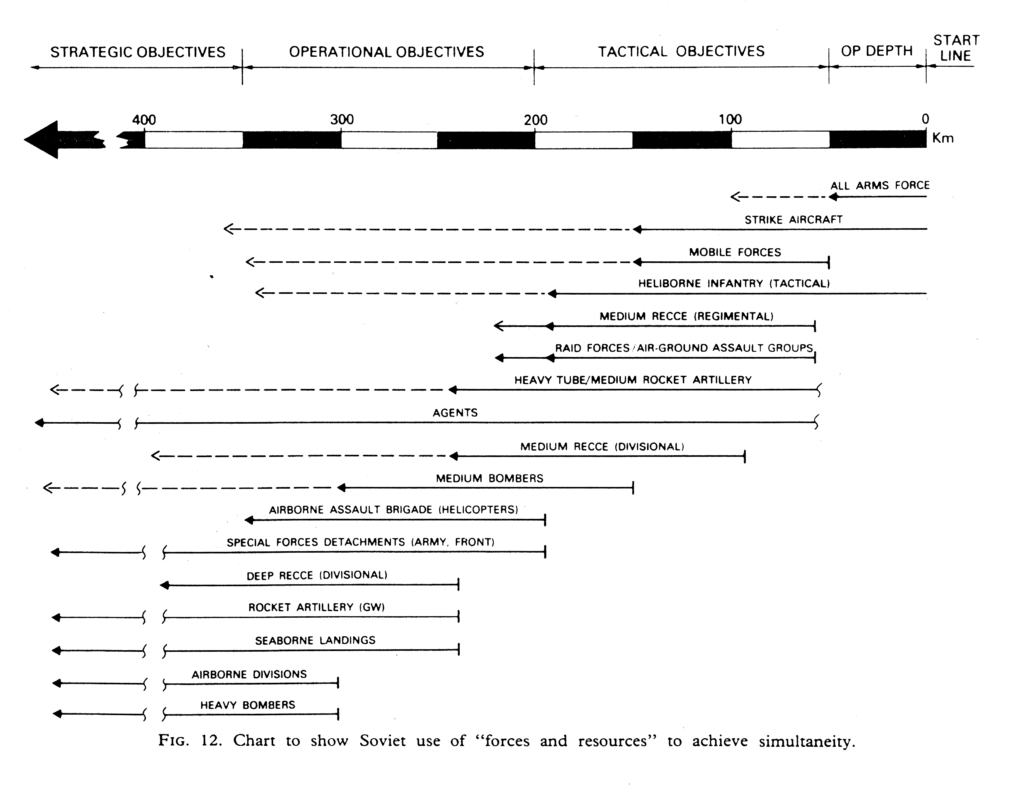

The concept evolved during the development of the Russian/Soviet operational concept of “deep battle” after World War I to encompass the interchangeability of fire and maneuver. In Soviet military thought, the battlefield effects of fires and the operational maneuver of ground forces were equivalent and complementary.

This principle continues to shape contemporary Russian military doctrine and practice, which is, in turn, influencing U.S. thinking about multi-domain operations. In fact, the idea is not new to Western military thinking at all. Maneuver warfare advocates adopted the concept in the 1980s, but it never found its way into official U.S. military doctrine.

An Idea Who’s Time Has Come. Again.

So why should the U.S. military doctrine developers take another look at interchangeability now? First, the increasing variety and ubiquity of long-range precision fire capabilities is forcing them to address the changing relationship between mass and fires on multi-domain battlefields. After spending a generation waging counterinsurgency and essentially outsourcing responsibility for operational fires to the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy, both the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps are scrambling to come to grips with the way technology is changing the character of land operations. All of the services are at the very beginning of assessing the impact of drone swarms—which are themselves interchangeable blends of mass and fires—on combat.

Second, the rapid acceptance and adoption of the idea of cross-domain fires has carried along with it an implicit acceptance of the interchangeability of the effects of kinetic and non-kinetic (i.e. information, electronic, and cyber) fires. This alone is already forcing U.S. joint military thinking to integrate effects into planning and decision-making.

The key component of interchangability is effects. Inherent in it is acceptance of the idea that combat forces have effects on the battlefield that go beyond mere physical lethality, i.e. the impact of fire or shock on a target. U.S. Army doctrine recognizes three effects of fires: destruction, neutralization, and suppression. Russian and maneuver warfare theorists hold that these same effects can be achieved through the effects of operational maneuver. The notion of interchangeability offers a very useful way of thinking about how to effectively integrate the lethality of mass and fires on future battlefields.

But Wait, Isn’t Effects Is A Four-Letter Word?

There is a big impediment to incorporating interchangeability into U.S. military thinking, however, and that is the decidedly ambivalent attitude of the U.S. land warfare services toward thinking about non-tangible effects in warfare.

As I have pointed out before, the U.S. Army (at least) has no effective way of assessing the effects of fires on combat, cross-domain or otherwise, because it has no real doctrinal methodology for calculating combat power on the battlefield. Army doctrine conceives of combat power almost exclusively in terms of capabilities and functions, not effects. In Army thinking, a combat multiplier is increased lethality in the form of additional weapons systems or combat units, not the intangible effects of operational or moral (human) factors on combat. For example, suppression may be a long-standing element in doctrine, but the Army still does not really have a clear idea of what causes it or what battlefield effects it really has.

In the wake of the 1990-91 Gulf War and the ensuing “Revolution in Military Affairs,” the U.S. Air Force led the way forward in thinking about the effects of lethality on the battlefield and how it should be leveraged to achieve strategic ends. It was the motivating service behind the development of a doctrine of “effects based operations” or EBO in the early 2000s.

However, in 2008, U.S. Joint Forces Command commander, U.S Marine General (and current Secretary of Defense) James Mattis ordered his command to no longer “use, sponsor, or export” EBO or related concepts and terms, the underlying principles of which he deemed to be “fundamentally flawed.” This effectively eliminated EBO from joint planning and doctrine. While Joint Forces Command was disbanded in 2011 and EBO thinking remains part of Air Force doctrine, Mattis’s decree pretty clearly showed what the U.S. land warfare services think about battlefield effects.