The Dupuy Institute (TDI) are sitting on a number of large combat databases that are unique to us and are company proprietary. For obvious reasons they will stay that way for the foreseeable future.

The original database of battles came to be called the Land Warfare Data Base (LWDB). It was also called the CHASE database by CAA. It consisted of 601 or 605 engagements from 1600-1973. It covered a lot of periods and lot of different engagement sizes, ranging from very large battles of hundreds of thousand a side to small company-sized actions. The length of battles range from a day to several months (some of the World War I battles like the Somme).

From that database, which is publicly available, we created a whole series of databases totaling some 1200 engagements. There are discussed in some depth in past posts.

Our largest and most developed data is our division-level database covering combat from 1904-1991 of 752 cases: It is discussed here: The Division Level Engagement Data Base (DLEDB) | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

There are a number of other databases we have. They are discussed here: Other TDI Data Bases | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

The cost of independently developing such a database is given here: Cost of Creating a Data Base | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

Part of the reason for this post is that I am in a discussion with someone who is doing analysis based upon the much older 601 case database. Considering the degree of expansion and improvement, including corrections to some of the engagements, this does not seem a good use of their time., especially as we have so greatly expanded the number engagements from 1943 and on.

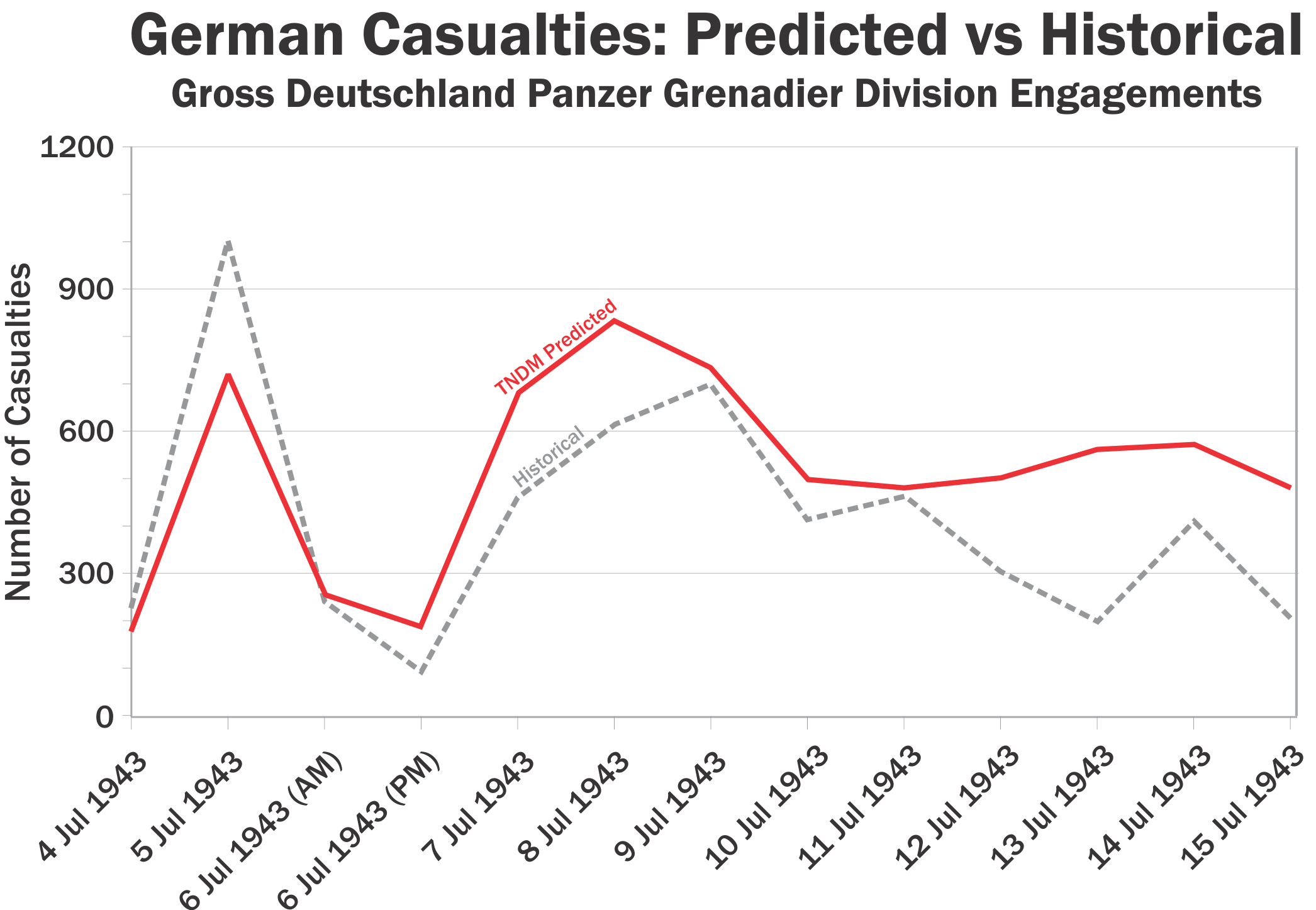

Now, I did use some of these databases for my book War by Numbers. I am also using them for my follow-up book, currently titled More War by Numbers. So the analysis I have done based upon them is available. I have also posted parts of the 192 Kursk engagements in my first Kursk book and 76 of them in my Prokhorovka book. None of these engagements were in the original LWDB.

If people want to use the TDI databases for their own independent analysis, they will need to find the proper funding so as to purchase or get access to these databases.