I do have a chapter on Afghanistan in my book America’s Modern Wars. When it came to updating the Afghanistan chapter (as I had to update the book before it was published), I ended up leaning on the Secretary General reports quarterly reports on Afghanistan for my data, as it may be the most trusted source available. Those reports are here:

https://unama.unmissions.org/secretary-general-reports

In Chapter Twenty-One my book I note that in 2013 there were 20,093 security incidences or 1,674 a month. This is a definite increase since 2008 and 2009 (741 and 960 a month respectively) and only a slight improvement (decrease) from 2011 (1,909 incidences a month). See pages 259-261 of my book.

So what are the current statistics?:

Security Incidences Civilian

Year Incidences Per Month Deaths

2013 20,093 1,674 2,959

2014 22,051 1,838 3,699

2015 22,634 1,886 3,545

2016 23,712 1,976 3,498

2017 23,744 1,979 3,438

2018 19,995 1,666 3,384 Estimated

2011 was the worse year of the war as far as incident count until 2016 and 2017. Based upon incident count, the war has been pretty much “flat-lined” for the last nine years (2010: 19,403, 2011: 22,903, 2012: 18,441). Civilian deaths show that same pattern.

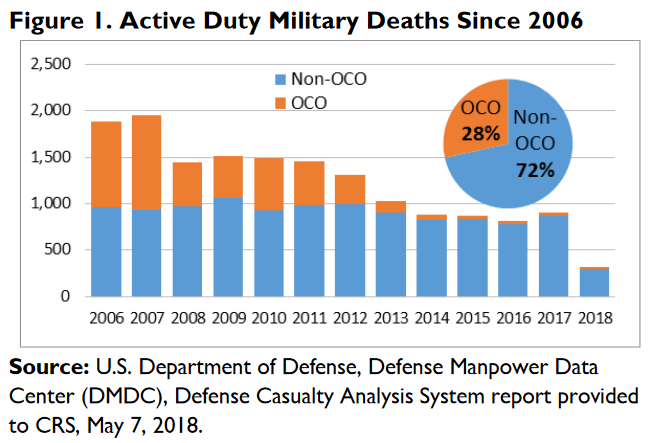

At the start of 2013, we still had 66,000 troops in Afghanistan, although we were drawing them down. There were 251 U.S. troops killed in 2012 (310 killed from all causes) and 85 in 2013 (127 killed from all causes). Over the course of 2013, 34,000 troops were to be withdrawn and the U.S. involvement to end sometime in 2015. We did withdrawn the troops, but really have not ended our involvement. According to Wikipeida we have 18,000+ ISAF forces there (mostly American) and 20,000+ contractors. I have not checked these figures. We left behind an Afghan force of over 300,000 troops to conduct the counterinsurgency. That force has not grown significantly in size since then.

As we note in my book “The 2013 figure of 20,093 incidents a year does argue for a significant insurgency force. If we use a conservative figure of 333 incidents per thousand insurgents, then we are looking at more than 60,000 full-time and part-time insurgents.”

Now, we actually never did have a contract to do work on Afghanistan. After we were right on Iraq in 2004 (casualties and duration), we were given contracts to do more data research and analysis of insurgencies, but never given a contract to further refine our predictions for Iraq or do a similar prediction for Afghanistan. So we have never done any in-depth analysis of Afghanistan (you know, the type of work that requires a man-year or more of effort).

Notes for 2018 estimates:

-

15 December 2017-15 February 2018: 3,521 security incidences (6% decrease from previous year).

-

15 February-15 May: 5,675 security incidences (7% decrease from previous year).

-

15 May – 15 August: 5,800 security incidences (10% decrease from previous year)

-

First quarter of 2018: 763 civilian deaths.

-

Mid-year 2018: 1,692 civilian deaths.

.