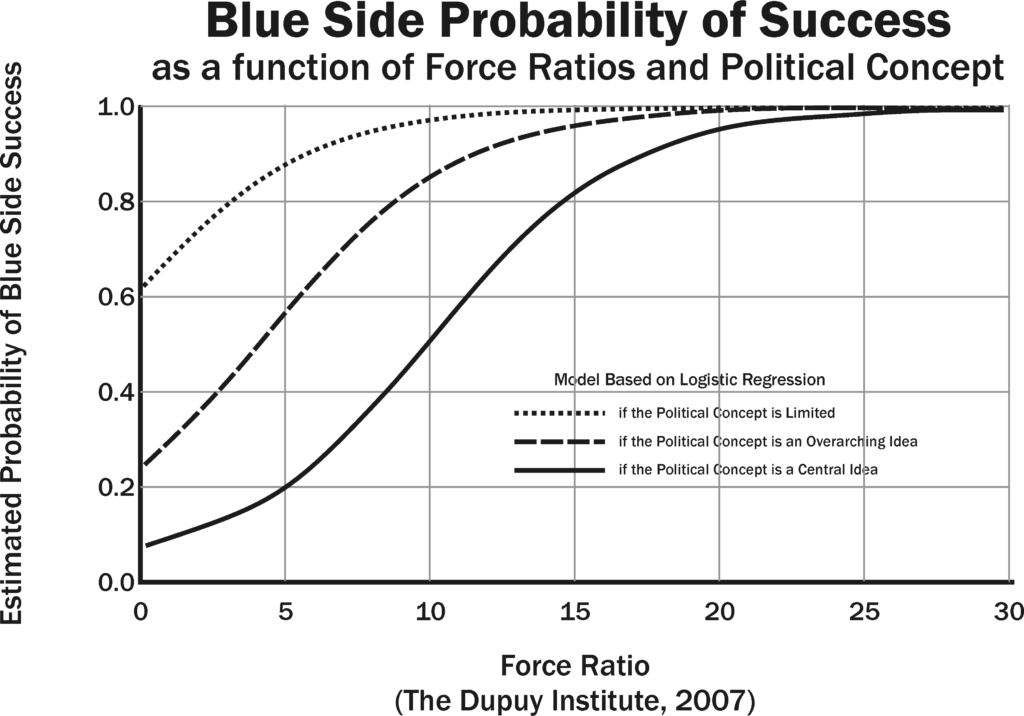

As many people are aware, the one logit regression that we had confidence in from the 83 insurgency cases we tested was a force ratio versus outcome model. This is discussed in the following blog post and in Chapter 6 of my book America’s Modern Wars.

The key was that we ended up with two very different curves: one if the insurgency was based upon a central idea (like nationalism) and a lesser curve if the insurgency was based upon limited political concept (a regional or factional insurgency). Now, we never really determined which applied to Afghanistan, because we actually never had a contract to do any work or analysis on Afghanistan. I am hesitant to reach conclusions without some research.

But let us look at the force ratios there now. I estimate that the insurgency has at least 60,000 full-time and part-time insurgents. There may have more than that. But, working backwards from the incident count of 20,000+ a year, and comparing those incident counts with insurgent strengths in past insurgencies, leads me to conclude that it is at least 60,000 insurgents. This process is discussed in depth in Chapter 11 of my book. Let’s work with that figure for a moment.

But let us look at the force ratios there now. I estimate that the insurgency has at least 60,000 full-time and part-time insurgents. There may have more than that. But, working backwards from the incident count of 20,000+ a year, and comparing those incident counts with insurgent strengths in past insurgencies, leads me to conclude that it is at least 60,000 insurgents. This process is discussed in depth in Chapter 11 of my book. Let’s work with that figure for a moment.

The counterinsurgent forces consist of supposedly almost 400,000 people. Except…in our model we only counted army and air force, and only counted police only if it was clear that counterinsurgent operations was their primary duty. Therefore our model did not count most police.

Parsing out the data in Wikipedia shows that the Afghan Army and Air Force total around 195,000 active in 2014. The Wikipedia source was this article: https://www.pajhwok.com/en/2015/03/10/mohammadi-asks-troops-stand-united. I have no idea how correct this number is. It might be a little optimistic (see my comments about auditing the police force rolls).

The Afghan National Police (ANP) have 157,000 members in September 2013 (again Wikipedia). I note that the UNAMA report in December 2018 on the audit reduced the ANP payroll from 147,875 to 106,189. But, this is a national police force. It includes uniformed police, border police, a criminal investigation division of 4,148 investigators, etc. Let’s say for convenience that half of them are doing traditional police work and half are doing counterinsurgent work. I have no idea if this is a good or reasonable split. So let’s say 53,000 ANP police involved in the counterinsurgency effort. The Afghan Local Police (ALP) are 19,600 as of February 2013. As they are clearly part of the counterinsurgency effort, I will count them.

The 18,000 ISAF are mostly training, so I am not sure how they should be counted, but we will count them. No sure if we should count the 20,000 contractors, as quite simply, there were not a lot of contractors in our previous 83 cases. The use of private contractors to fight insurgencies is a relatively new approach. For now I will not count them.

So, let’s count counterinsurgent strength at 195,000 + 53,000 ANP + 19,600 ALP + 18,000 ISAF. This gives a counterinsurgent strength of 285,600 compared to an insurgent strength of 60,000. This is a 4.76-to-1 force ratio. This is a very precise number created from some very fuzzy data.

Now, if I look at the curve for an insurgency based upon an limited political concept, and I see that an 4.76-to-1 force ratio means that the counterinsurgent won roughly 86% of the time (see page 65 of my book). This is favorable. But right now, it doesn’t really look like we have been winning in Afghanistan over the last eight years.

On the other hand, if I code this as an insurgency based upon a central idea I see that a 4.76-to-1 force ratio results in the counterinsurgent winning 19% of the time. This is much worse.

So…I have yet to make a determination as to which curve should apply in this case. Perhaps neither do, as Afghanistan is a unique and complex case. Properly analyzing this would require a level-of-effort beyond what I am willing to invest. Keep in mind that our Iraq estimate was funded in 2004 (see Chapter 1 of my book). It was also ignored.

Very interesting, thanks for posting. If it were considered as an ‘ideology’ (your middle category IIRC) would that materially affect the result?

It could. In all the historical cases we looked at the “ideology” was communism. I would have to go back an analyze the Afghan insurgents to see if that is really an equivalent. Part of the problem is there are multiple insurgent groups with different leaders with different goals. As it is, the “ideology” was sometimes not the primary driver. For example, in Vietnam the insurgency had significant underlying nationalism elements.

Of course, if the political concept of the insurgency is an “Overarching Idea” then at the current force levels that odds of the counterinsurgency winning is more like 57%.

Logit rules!

Assuming the central political concept curve seems reasonable to me for those groups for which the political/religious concept is considered to be a form/vision of Islam. For those groups that are more about gaining opportunistic advantage for a family/clan/tribe, the limited political concept seems reasonable. One could assign a concept level to each group and use each group’s force level relative to an assumed counter-force level to suggest the odds of success. This might also suggest a counter-force strategy of timing and massing of counter-force operations to defeat each group in turn (either operating against forces in order of greatest chance for success so as to build morale momentum or in order of most formidable of the remaining opponents so as to have less of a need to assign large holding forces to restrain the groups not currently being countered/defeated.

I am drafting up a blog post in response to this comment. May post it up next week.

OK NB…..made a post today that somewhat addresses this question.

It was a good post (including its accompanying article). Thanks, Chris.

Oops! That should have been “its” rather than “it’s” — I obviously didn’t have my good grammar at my (in) my finger tips!

Corrected. I find I end up doing minor editing on a lot of my blog posts after I post them.

Digging the hole deeper by my misplacement of the parenthesis — seems to be a parable for trying to do things in Afghanistan!