My colleague Chris Lawrence has taken me to task with regard to my last post on the topic of morale. I asserted that Trevor Dupuy’s claim that human factors influenced the outcome of combat was controversial. Chris pointed out that it was, in fact, Col Dupuy’s claims that 1) human factors in combat could be measured and quantified; and 2) that quantified human factors should be incorporated into combat models, that were really the sources of controversy.

Chris is indisputably correct about that. In my defense, I chose the wording I used in my post deliberately to weasel around an apparently problematic contradiction. While Col Dupuy did indeed believe that human factors in combat could be quantified, he was dubious about the prospect of individually quantifying some of those specific factors, including morale. Since my post was primarily about Dr. Fennell’s work on morale, I side-stepped that issue. Well, today I am going to wade on in.

Col Dupuy first addressed the quantification of human factors in combat in his book Numbers, Predictions & War, published in 1979. His original combat model, the Quantified Judgment Model (QJM), incorporated 73 different variable elements and parameters, including 11 he defined as intangible. By intangible, he meant variables “which are – at least for the present – impossible to quantify with confidence, either because they are essentially qualitative in nature, or because for some other reason they currently defy precise delineation or measurement.”[1] He also believed that “some (such as logistics) may lend themselves to assessment indirectly through the measurement of their effects.”[2]

He divided those intangible variables into three categories[3]:

|

Sometimes calculable |

Probably calculable; not yet calculated |

Intangible; probably individually incalculable |

|

|

|

With regard to leadership, training, and morale, Col Dupuy asserted that

These subjective qualities are almost impossible to assess in absolute terms with complete objectivity. However, the relative capabilities of the opposing leaders in terms of skill, nerve, and determination can probably have more influence on the outcome of a battle than any of the other qualitative variables of combat— if there is a substantial difference in the qualities of leadership of the opposing sides. The same is true, probably to a somewhat lesser extent, if there are substantial differences in the state of training or of combat experience of the two sides, and if there are great differences in their respective states of morale. Accordingly, where solid historical information warrants, these three variables can be given mathematical weights, either individually, or in relationship with the other elements of combat effectiveness, on the basis of professional military judgment, but (under the present “state of the art”) this weighting process is bound to be highly subjective.[4]

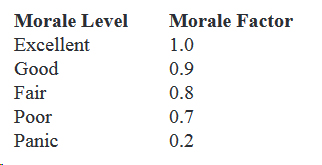

Col Dupuy included morale as an independent variable in the QJM’s combat power formula and offered a table of suggested values [5]. However, he did not explain in any detail how to assess morale or apply it in the QJM.

As I quoted in my last post, as of 1987, Col Dupuy continued to contend ambivalently that “even though it may not be easily defined and can probably never be quantified, troop morale is very real and can be very important as a contributor to victory or defeat.” He never resolved this seeming contradiction in his writings, but as with several of the intangible variables he identified, he did acknowledge the potential for defining and quantifying some of them. Dr. Fennell’s demonstration of a strong correlation between morale level and rates of sickness, battle exhaustion, desertion, absence without leave and self-inflicted wounds suggests, at least in the British Second Army in northwest Europe in 1944-45, a potential methodology for quantifying morale which could allow its impact to be measured indirectly in much the same manner Col Dupuy measured combat effectiveness. Whether or not the notion of doing so remains controversial will be interesting to see.

NOTES

[1.] Trevor N. Dupuy, Numbers, Predictions & War: Using History To Evaluate Combat Factors And Predict The Outcome Of Battles (New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1979), p. 36

[2] ibid., p. 37.

[3] ibid., p. 33.

[4] ibid., p. 37-38.

[5] ibid., p. 231.

There was an article by Bing West, The Strike Teams: Tactical performance and strategic potential, in the May 2016 issue of Marine Corps Gazette. He made a comment on how the “The morale of a unit is worse affected by constant small attrition than a few major engagements.” He goes on to say that it easier for troops can handle casualties from a major engagement. But when they experience constant stress and constant casualties, even when the casualty rate is very low, the psychological impact of the enemy’s actions have an impact out of proportion to the enemies numbers.

Jose, thank you for the reference. The article is interesting. It appears to be a reprint of a paper Bing West originally wrote for RAND and presented at a conference in 1968. [https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2005/P3987.pdf]

West appears to confine his observations to what he calls “strike teams,” largely comprised of highly professional troops best described as elite. Col Dupuy observed that the performance of units with high levels of combat effectiveness would likely not be adversely affected by poor morale. Low morale would probably have a greater effect on the combat performance of average or low-quality forces.