Numbers matter in war and warfare. Armies cannot function effectively without reliable counts of manpower, weapons, supplies, and losses. Wars, campaigns, and battles are waged or avoided based on assessments of relative numerical strength. Possessing superior numbers, either overall or at the decisive point, is a commonly held axiom (if not a guarantor) for success in warfare.

These numbers of war likewise inform the judgements of historians. They play a large role in shaping historical understanding of who won or lost, and why. Armies and leaders possessing a numerical advantage are expected to succeed, and thus come under exacting scrutiny when they do not. Commanders and combatants who win in spite of inferiorities in numbers are lauded as geniuses or elite fighters.

Given the importance of numbers in war and history, however, it is surprising to see how often historians treat quantitative data carelessly. All too often, for example, historical estimates of troop strength are presented uncritically and often rounded off, apparently for simplicity’s sake. Otherwise careful scholars are not immune from the casual or sloppy use of numbers.

However, just as careless treatment of qualitative historical evidence results in bad history, the same goes for mishandling quantitative data. To be sure, like any historical evidence, quantitative data can be imprecise or simply inaccurate. Thus, as with any historical evidence, it is incumbent upon historians to analyze the numbers they use with methodological rigor.

OK, with that bit of throat-clearing out of the way, let me now proceed to jump into one of the greatest quantitative morasses in military historiography: strengths and losses in the American Civil War. Participants, pundits, and scholars have been arguing endlessly over numbers since before the war ended. And since nothing seems to get folks riled up more than debating Civil War numbers than arguing about the merits (or lack thereof) of Union General George B. McClellan, I am eventually going to add him to the mix as well.

The reason I am grabbing these dual lightning rods is to illustrate the challenges of quantitative data and historical analysis by looking at one of Trevor Dupuy’s favorite historical case studies, the Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg, for the unreconstructed rebels lurking out there). Dupuy cited his analysis of the battle in several of his books, mainly as a way of walking readers through his Quantified Judgement Method of Analysis (QJMA), and to demonstrate his concept of combat multipliers.

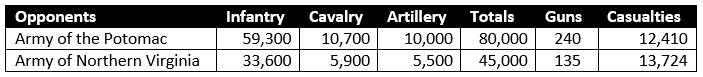

I have questions about his Antietam analysis that I will address later. To begin, however, I want to look at the force strength numbers he used. On p. 156 of Numbers, Predictions and War, he provided the following figures for the opposing armies at Antietam: The sources he cited for these figures were R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Compact History of the Civil War (New York: Hawthorn, 1960) and Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and Losses of the Civil War (reprint, Bloomington: University of Indiana, 1957).

The sources he cited for these figures were R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Compact History of the Civil War (New York: Hawthorn, 1960) and Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and Losses of the Civil War (reprint, Bloomington: University of Indiana, 1957).

It is with Livermore that I will begin tracing the historical and historiographical mystery of how many Confederates fought at the Battle of Antietam.

Well summarized, I fully agree and might add that even if the data is reliable or accurate, most interpretations often are still false or context is fully ignored.

“OK, with that bit of throat-clearing out of the way, let me now proceed to jump into one of the greatest quantitative morasses in military historiography”.

I was always under the impression that the American Civil War was rather well documented (with the exception of later phases for the Confederate Army) and misinformation was based on poor literature or because it received little attention elsewhere (such as Europe).

To get a better understanding or run any simulations, I always took the next best thing and oriented myself on the Boshin conflict or 1870/71 to find analogies.

Even though plentiful, the body of American Civil War quantitative data is not as inherently objective as it might seem, and there are a lot of interesting caveats that need to be taken into account when using them. Disputes over that data have driven debates that began before the war ended and many extend to the current day. It’s all quite fascinating and I plan to delve into detail in future posts.

I have often wondered how much good combat data might be available for analysis from 1870-71. Do you know what the state of the French and Prussian/German archives are in?

I am no authority on the Franco-Prussian war, but due to the cooperation of both nations there is a decent overview of the conflict. The war was also very omnipresent in the gazettes at that time, so a lot of information exists, besides POW reports, diaries and (local) archive material.

I can merely comment on the losses: Here is an overview (with their respective names), categorized in S.v. = schwer verwundet (heavily wounded), T = todt (old german for “tot”, dead), Laz = Lazareth (that one is obvious, field hospitals), Laz.unb.= Lazareth unbekannt (unkown), Sch. = Schuß (gunwounds),

overall registered:

41.000 Prussian soldiers, 139.000 french.

or information for infantry regiments: KIA 35%, DOW 27%, typhus 20%, dysentery 8%, variola 1,3%.

http://www.denkmalprojekt.org/verlustlisten/verlustlisten_1870-71.htm

http://wiki-commons.genealogy.net/images/1/1d/Verlustliste_1870_Seite_1.jpg

Id say that data for individual battles (strengths) however is rather scarce and not particularly reliable either, there is good information on the technical side of things, i.e. items such as the Chassepot and Dreyse are popular amongst enthusiasts.

Shawn,

34,708 present for duty…more or less.

Really? That’s even lower than Taylor’s estimate of effectives and Carmen’s estimate of engaged. What do you base that on?

Here is a good summary for Antietam: http://67thtigers.blogspot.com/2016/03/confederate-strength-at-antietam.html

Brynn/67th Tigers has done some very interesting research on the topic of Civil War numbers.

Shawn,

67thTigers is a fraud.

Those figures are from a spreadsheet working up the totals from Carmen and additional research Curt did while we worked on Artillery He’ll. They are based on the regimental PFD.

Did you and Curt write up your estimate somewhere? I looked in Artillery Hell but I did not see a reference. Would you be interested in presenting it here?

One reason I started this series of posts was to look at various estimates and claims, such as those advanced by 67th Tigers. What he has presented did not strike me as fraudulent, but I could stand to be corrected if so.

Shawn,

I’d be happy to email you the spreadsheet, if I still have your current correct email.

67thTigers used to post frequently at TankNet and other sites. He has a habit of “citing” sources that don’t actually say what he claims they say. The worst was when he posted a reference to an MA thesis by one of Doctor Harsh’s students to back up his claims. I took the time and trouble of going to my alma mater GMU to copy the thesis, read it, and find out that it actually said exactly the opposite of 67thTigers claims. The exchange was:

“67th Tigers Tue 4 Aug 2009 1619:

Yet you missed the currently accepted “correct” numbers;

Tenney, L., “Seven Days in 1862: The Union and Confederate numbers before Richmond”, unpublished Masters thesis, GMU (1992). It lists a strength of 112,200 PFD, excluding the 44th Alabama and 52nd Georgia, arriving during the battle. The same thesis credits 101,434 PFD to the Union force. This includes forces in theatre but not engaged (such as the CS garrison of Petersburg, the Union logistics base at White House Landing &c.).”

My reply (note that GMU did not distribute thesis copies, so the only way 67th Tigers could have accessed Tenney was by going to the GMU library):

“Of course, the real problem was not that I had “missed” anything, it was that Tigger had never seen Tenney, had no clue what Tenney had actually said, was also clueless as to how Tenney’s figures were derived, or what they included and excluded. In reality, he was quoting from Harsh and claiming it was Tenney, deciding to take the dishonest student’s way out and pretending that he was quoting from the original source rather than from a secondary interpretation of it. The problem with that decision of course was that he was unable to explain why there were three different figures for Lee’s strength (his original “114,000”, Harsh’s 106,430, and Rafuse’s 112,200, the latter two of which appear in footnotes in Harsh’s Confederate Tide Rising. Note also that his former claim of 96,000 Union troops is actually 101,434 in the source he has given. He also apparently decided that I was too dumb to recognize the deception. For that matter, he apparently thought that no one at TankNet would question him quoting an obscure thesis produced 17 years ago in a not particularly well-known American university. After all, we’ve all learned over the years just how impeccable his source references are and have never had occasion to question him about them.

In fact, Tenney’s methodology was based on that of Busey and Martin, as would be expected since they pioneered modern regimental strength investigation 37 years ago. Like those, Tenney’s figures are derived from multiple sources, primarily the muster reports held by the US National Archives in RG 94, the compiled versions of which are frequently found in the O.R., the army, divisional, brigade, and regimental reports in the O.R., and various papers and other documents of the participants. Tenney of course first established the most reasonable common denominator would be to utilize the terms found in the musters themselves, which required a careful understanding of their meaning (Tigger of course has never been able to distinguish the definitions, being too eager to fabricate his own definitions and numbers, but I confess I was also surprised at some of Tenney’s findings). Those categories included:

Aggregate Present for Duty – available for training or active combat operations, which included as separate categories:

Present for Duty (sometimes given as Present for Duty, Equipped but only by the Union Army, and otherwise it might include men without arms or cavalry without horses)

Extra Duty – (sometimes “special” duty) those assigned as teamsters, quartermasters, hospital attendants, or other support duties

Daily Duty – those assigned as cooks, tailors, and orderlies

Sick – in camp

In arrest – in camp

Note that commissary and quartermaster sergeants, musicians, artificers, farriers, blacksmiths, saddlers, and wagoners that appeared as part of the regular regimental organization were not considered as extra or daily duty.

Absent – that included:

Furloughs

Sick – in hospital or at home

Wounded – in hospital or at home

Prisoners – not exchanged

AWOL

Aggregate Present and Absent included the two subcategories. It decreased due to known desertions (a confirmed deserter was no longer AWOL), killed and deaths, and missing in action. It increased because of transfers, recruits, recovered deserters, or returns from missing in action.

Now here it starts to get a bit complicated. During this period the Union Army of the Potomac included as “Present for Duty” those officers and men listed as “Extra Duty” on the 10 and 20 June consolidated reports, but not on the 30 June monthly report. They also apparently did the same in April and May and continued to do so until August. Tenney found that the correction for that error, based upon the difference found in the monthly report, was approximately 5%, which he used as an adjustment to the present for duty strength on 20 June.

Note that although Tigger has implied that somehow the Union reports are inaccurate or even falsified, Tenney himself describes them as “accurate”, when the necessary adjustment is included, and also describes the monthly reports, which did not appear in the O.R., as accurate. On the other hand, he notes the paucity of the Confederate records and how it was necessary to utilize “great care” in deriving accurate figures for their army on 20 June. However, the Confederate figures are still problematic, for example, the figure given for the 15th VA on 20 June is 476, exactly the same as that given as its “effective strength” on 30 April at Williamsburg.

One consistent problem Tenney found was the use of Johnston’s 21 May report, which uses the term “effective” to describe the regimental strength. Tigger, like many (including me), has apparently incorrectly assumed that “effective” was shorthand to describe the number of men taken into battle by the regiment. Unfortunately, it was not. “Effective total” in fact was a usage peculiar to the Confederate Army at this time and included enlisted men “present for duty”, plus “extra duty”, plus “in arrest”, but excluded all officers. Its usage led to such confusion that Lee in fact directed that it no longer be used when he assumed command (as did Bragg in the AoT in 1863). Unfortunately it is unclear how closely that order was observed, while it still led to confusion both of its wartime meaning and what the postwar interpretation of the term was. Tenney notes that Livermore attempted to compensate for it and that his “percentage generally agrees with the deduction necessary for the extra duty men listed in the complete strength return” (so much for Livermore’s figures being “suspect”). Unfortunately the devil is in the details so even though Livermore was conceptually correct, in the case of the Seven Days he was off a bit, since he tried to balance the AoP figures in a similar way (he was trying to determine the number engaged after all), but was unaware of the similar discrepancy in the AoP accounting; from March 1862 to October 1862 their calculated Present for Duty, Equipped was exactly equal to their Present for Duty. Thus he made a conceptually correct adjustment to the Confederate strength, but then reduced the Union strength as well, which was unnecessary in this case.

Rather than the confusing term “effectives” Tenney preferred using “carried into battle” which does appear frequently in both Union and Confederate reports. However, he rightly notes the difficulty of using that in a meaningful way for comparing these series of battles. The Seven Days saw considerable marching and fighting, and each engagement involved different elements and changing strengths as straggling affected both armies. Furthermore, Tenney saw “carried into battle” as a measure of effectiveness, giving the example of Cobb’s Brigade, which had lost about 40% of their PFD on 20 June by the time they reached Malvern Hill, only a fraction of which were due to battle casualties. As a result, he uses the PFD strength for both forces on 20 June as his baseline.

In terms of sickness Tenney found that in the Union Army it went from 9.53% at the end of June to 14.17% at the end of July. Earlier on 9 May it was reported that the evacuated sick totaled 950 and that 2,000 were in hospital, so roughly half of the 5,618 reported sick were serious enough to be hospitalized or evacuated and the total sick rate was 5.1% of the 109,335 reported PFD on 30 April.

Since data for the Confederate side was fragmentary Tenney was only able to report a few examples for them, the 27th N.C. had 642 PFD on 20 June, 102 sick at the end of June and 162 at the end of July. It seems likely that although the rate in that regiment was higher than the Union overall rate, the two armies were probably similar.

Again, there is absolutely no evidence that the figures made up by Tigger for a “normal” sick rate of 25% and a range of 16.7% to 33.3% being found for “most” armies (which, where, when “most”?).”

Rich, excellent work, as usual! This definitely undermines the validity of Brynn/76th Tigers online assertions and should stand as a perfect example of the effort historians need to make to properly interrogate quantitative evidence.

The gritty details of the manpower counting are exactly what I was hoping to get into with this series of blog posts. You clearly know more about it than I do, so thank you for contributing this.

I am definitely interested in the spreadsheet, and I have a couple of other things to bounce off you if you have the time. I’ll get in touch offline.

Hi Shawn,

I sent you an email at your last known address. At least that my computer had. Did you get it?

Rich

A fascinating question. The numbers Dupuy used were from his own “Compact History of the Civil War”, and were unreferenced in that.

Lee’s returns show he left the field with a little over 40,000 effectives. The field return of the 22nd September shows 37,330 effectives (i.e. PFD as Lee defined it, excluding extra-duty men etc.) excluding the cavalry and reserve artillery. The cavalry was probably about 4,500 on the field, excluding horse artillery (as several regiments with about 1,200 cavalrymen were detached), and the first available return of the artillery reserve is 771 PFD (30th September). The horse artillery on the field were ca. 200 (less 4 guns left on the far bank). This gives about 42,801 after Antietam. The rebels acknowledge the loss of 13,724 in the action, and adding them would give 56,325 on the field. However, ca. 1,138 infantry were not on the field (Livermore, using pro-rata counts), and by battery counting 9/19th of the reserve arty (406) weren’t. This means Lee left the field with roughly 41,257 effectives, and had about 54,981 effectives on the field during the battle.

The 5,900 strength above for the rebel cavalry is approximately correct, including horse arty and detached regiments (such as the 6th and 10th Va), but only 4,500 cavalry and 200 horse artillery were actually on the field.

The 135 guns is a nonsense, and I believe was probably based upon post-battle reports where “short ranged guns” (i.e. 6 pdrs and 12 pdr howitzers) were excluded. The ANV had 337 guns prior to crossing the Potomac, but left 36 guns at Leesburg and crossed with 301 guns. They had 239 guns actually on the field on the 17th, but not all were engaged. 59 guns were elsewhere, and 3 had been lost prior to the battle. 135 is about correct for rifled guns, 12 pdr Napoleon’s etc., and the rest were “short range guns” of less combat power.

The question of the actual infantry strength on the field is more awkward as 5-6,000 stragglers caught up during the battle of the 17th, and the same again in the evening. Carman estimates 29,222 effectives, excluding 3 unengaged brigades and some regiments who were on the field (15th Ga, 17th Ga, Phillip’s Legion etc.). This may be low, as some of the figures given are for the 16th. Notably the strength of the Stonewall Division is that of it coming off a forced march, and excludes any laggards who caught up on the evening of the 16th. A memoir of an officer in Garnett’s brigade notes that while they only counted 250 on the morning of the 17th (going into the fight), but so many of their stragglers came up that the next day they counted twice this despite heavy casualties. 33,600 infantry effectives is a lower bound. I personally think about 39,000 infantrymen fought.

In terms of cavalry, 10,700 is about correct for the whole of the cavalry arm in the Virginia theatre, including that not on the field (such as the brigades left at Washington, and McReynolds’ detachment at Gettysburg). Only about 4,000 cavalry were actually on the field.

Of course, the Federal numbers are perhaps quite overestimated. In terms of effectives, the Federals had ca. 34,300 experienced/ veteran infantry, about 12,000 newly levies, about 4,000 cavalry and 280 guns (inc. horse arty).

In basic terms, the Federals had more infantry, but their advantage there was in the newly recruited levies, they had more and better artillery, and a bit less cavalry.