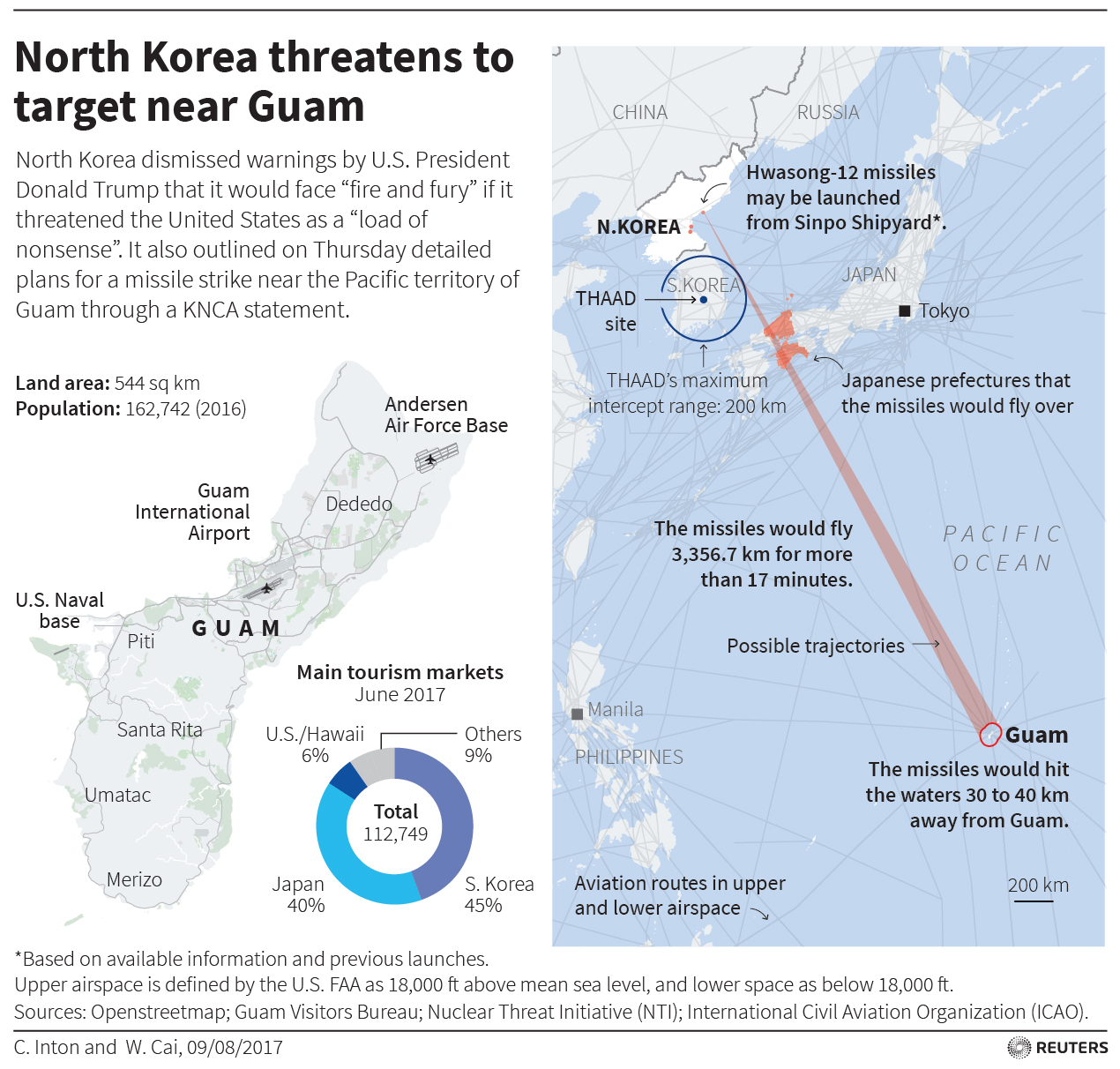

Gerry Doyle has an excellent article in The New York Times exploring the issue of defending the island of Guam from a potential North Korean ballistic missile threat. In response to President Donald Trump’s comments earlier this week, North Korea issued an oddly specific threat to conduct a ballistic missile test targeting the area around Guam.

Key takeaways from the article:

- The U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ballistic missile (BMD) system based in South Korea would have no chance of intercepting a Hwasong-12 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) during its initial ascent (boost-phase). THAAD is not designed for boost-phase intercept.

- Japan fields a sea-based U.S. Aegis BMD equipped with SM-3 missiles, which is designed to intercept short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles at the middle (mid-course) and final (terminal phase) parts of their flight. It is likely that a Hwasong-12 moving toward Guam would be out of SM-3 range as it passed over Japan, however.

- Guam itself is defended by a layered BMD system including sea-based U.S. Aegis, THAAD, and Patriot PAC-3 batteries, which are all designed to engage incoming ballistic missiles during mid-course and terminal phase. This is where an intercept would most likely occur.

Despite possessing the technical capability for intercepting a provocative North Korean missile test, Doyle points out a tricky policy problem for the U.S.

If Japan or the United States shoots down the missiles, North Korea could see it as an escalation, prompting a military response. If they do nothing, and allow the North Korean missiles to fly unharmed, it’s unclear how Pyongyang would interpret it.

On the other hand, if they try to intercept the missiles but fail, it could undermine the credibility of both countries’ assurances that their antimissile systems can work.

Stay tuned.