Another posting from William “Chip” Sayers. Part of his “Wargaming 101” series:

Wargaming 101: The Use of Wargames in Training

When I arrived at Defense Intelligence Agency in the summer of 1986, my assigned cubicle was just down the row from the guy who was on a one-year temporary duty assignment to run our new analyst training program. The Introduction to Defense Intelligence Research and Analysis (IDIRA) course was seven weeks packed with modules on various subjects, such as effective writing and briefing techniques, US Intelligence Community structure, organization of the Department of Defense, etc. The core of IDIRA was about a week’s study of each of the US military services and their warfare areas, including trips to several bases along the eastern seaboard. As a capstone exercise, the students did a couple of days of reading message traffic (it was all hardcopy, back then!) and building an understanding of an obscure, historical conflict, and then doing a, “now what happens?” briefing to the instructors and high-level DIA administrators. When the briefing was over, the instructors would brief-back the class on what really happened next and then critique the students’ performances.

The IDIRA program manager, was a good guy and we became friends before I ever took the class. One of my first questions was to ask if IDIRA made use of wargames as teaching tools. With the exception of a half-day logistics exercise in the ground warfare block, the answer was no. I immediately went to work on adapting a commercial board wargame for the air block. The base game was about the air war over North Vietnam and my playtest group included an analyst who had flown USAF F-4s during the conflict. Despite my best efforts, the game remained unduly cumbersome and the scale, as tested, was inappropriate for what I was trying to accomplish. Scratch attempt number one.

I took IDIRA myself in the Fall and as it happened, two of my classmates were avid commercial wargamers. Mark, an Army officer, Shane, an Air Force officer, and I had many discussions on how we might devise a wargame to replace my first effort. A couple of months after we graduated from IDIRA, Mark presented Shane and I with a game of his own devising which, if a little clunky, was of the scale we needed and was quite workable for student use. Over the next couple of years, I codified the rules and came up with lookup tables that allowed us to adjudicate combat in a realistic way without resorting to the use of a random number generator (dice). The students were always suspicious of dice, believing that the element of randomness made the exercise less realistic. In point of fact, it made combat more realistic by taking out a measure of easy predictability, but if it helped them to buy-in, so be it.

Over time, our game successfully got across to the students the lessons we wanted to impart and proved quite popular, always scoring as one of the best IDIRA blocks in the students’ critiques. I still have a stack of critiques in which every student in the class gave us a perfect score.

Meanwhile, the Navy team was not far behind us in developing their own game. Chris, a Navy officer and another friend of mine, taught the students to play an off-the-shelf naval wargame that he had codesigned. Again, the students absorbed what they were intended to learn and had fun doing it. And while we’re on the subject, I think fun is highly underrated. Over the years of my experience in using instructional wargames, the more “fun” the students had, the better they learned the lessons we were trying to get across. The students, with few exceptions, were usually highly competitive and could be counted on to delve into the games, enhancing the learning experience.

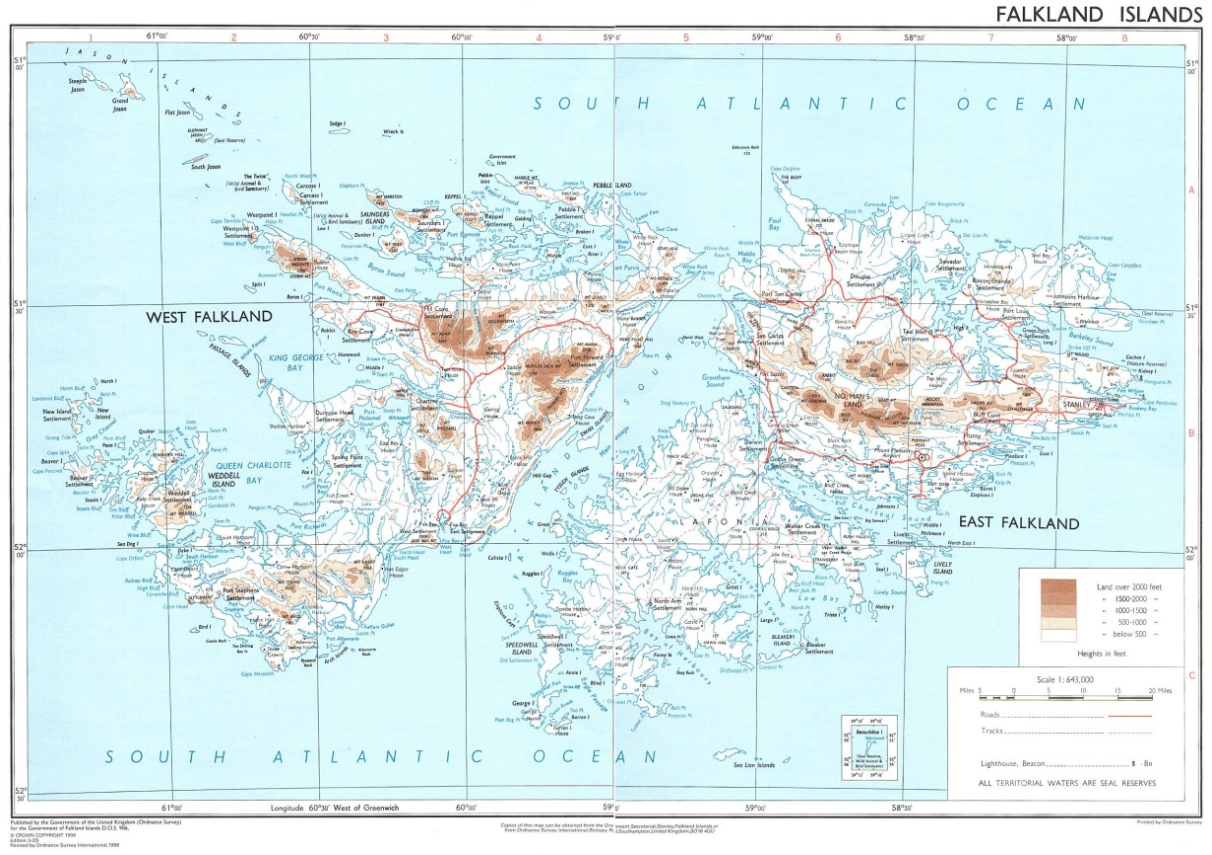

IDIRA never had a wargame for the ground forces block, other than the rather good logistics exercise, and Chris and I began to conspire to put together a wargame that would teach combined-arms warfare at the operational level. We would include air, naval and ground forces elements in the game and illustrate for the students how these warfare disciplines worked together to prosecute a campaign. There was only one choice for a historical campaign that I believed was small and sufficiently self-contained to be appropriate for our purposes: the 1982 Falklands War between Argentina and the UK.

A map from Larry Bond’s Resolution 502, an early scenario book for his Harpoon naval wargame.

A map from Larry Bond’s Resolution 502, an early scenario book for his Harpoon naval wargame.

To handle the air and naval aspects of the exercise, we used another off-the-shelf commercial game that Chris had coauthored, Harpoon. For the ground portion, we used the technique I outlined in a previous post, Wargaming 101: A Tale of Two Forces. We ran things a little differently for this exercise — the students were all playing the roles of various UK commanders, while the instructors provided a Red Cell directing the Argentine forces. Instructors not involved in the Red Cell advised the students such that they only had to make general decisions without having to have a deep understanding of the rules of the game. The students had to establish air and naval superiority sufficient to allow a landing, then march from the beaches to their objectives, eliminating resistance along the way. We allowed the students to choose their landing beaches pretty much as they wanted, and then critiqued their choice according to the practicality, defendability and potential to support offensive moves. When ground forces actually came into contact, I simply drew a ratio and gave the students the results: at ≤1:1, the students were rebuked for making a bad attack and were told to bring up reinforcements or abandon the effort. At less than 3:1, the students were merely advised to bring up reinforcements and try again, and at 3:1 or greater, the battle was a clear-cut victory and the British ground forces commander won appropriate kudos.

The students enjoyed the exercise because it wasn’t abstracted, it used real-world physics units (nautical miles, nautical miles per hour, etc.) that were comprehensible, the results of their decisions were immediately recognized and understandable. And there were genuinely tense and fun moments, particularly when the Argentine Air Force attacked the fleet. That was where our training wargames stood until a couple of years later when, as the program manager for IDIRA, I folded down the program — DIA wasn’t hiring new analysts in the mid-1990s, so they had no need for a new analyst training program.

Ironically, I had just won an interagency cooperation award from CIA for training our first Agency analyst when IDIRA was rather short-sightedly shut down. A couple of years later, the CIA believed that a replacement course was needed and stood up the Interagency Military Analysis Course (IMAC) within the Sherman Kent School. If DIA had been a bit faster on the draw, they could have been in the driver’s seat, but now they would be beholden to the CIA for training its analysts. Shrewd move. Soon after IMAC stood up, I was invited to become an instructor in their military aviation operations block.

When I joined the IMAC instructor staff, they already had a pretty good little Practical Exercise (PE) very similar to the one we used in IDIRA. However, IMAC’s PE had a nifty little twist. While the IDIRA PE used a generic order of battle, IMAC’s was based on a hypothetical confrontation between India and Pakistan. The scenario began with a terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament, which Indian intelligence believed came from Pakistan. The students on the Indian side were told that their Prime Minister had ordered a retaliation, but it was up to the students to decide what to hit, and with how much force. In every running of the exercise, without exception, the Indian side was restrained, limiting their response. While the students playing the Indian Air Force inevitably feared starting a wide conflict, their opponents playing the Pakistani Air Force were under no such compunctions. Just as inevitably, they felt their underdog status (with a considerably smaller and older force) drove them to an, “In for a penny, in for a pound” strategy. They assumed that the Indian Air Force would come crush them in any event, so they might as well go out in a blaze of glory. It was fascinating to watch the dynamic between the two teams play out this way every single time.

I helped make some refinements to this PE including “target folders” for the students to use in planning their attacks and codified rules, charts and tables for game play. The information was “real-world” from unclassified sources (such as Jane’s), but again, I leaned heavily on published commercial wargames, particularly Harpoon.

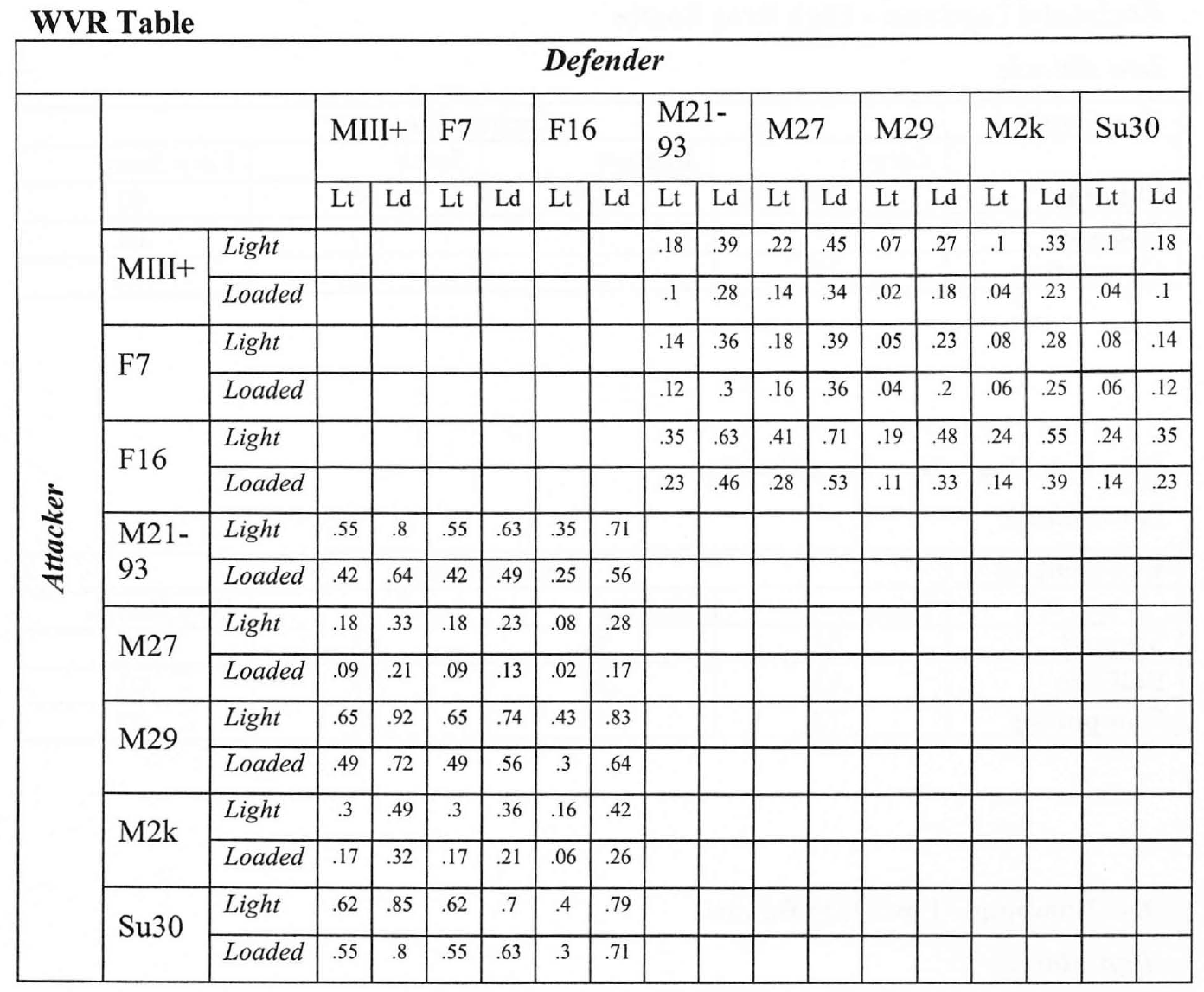

A simple lookup table for Within Visual Range combat (dogfighting). A lightly loaded Mirage III in a fight with a lightly loaded Su-30 would have a 10% chance of shooting down the Sukhoi, while the Su-30 would have a 62% chance of winning the fight.

A simple lookup table for Within Visual Range combat (dogfighting). A lightly loaded Mirage III in a fight with a lightly loaded Su-30 would have a 10% chance of shooting down the Sukhoi, while the Su-30 would have a 62% chance of winning the fight.

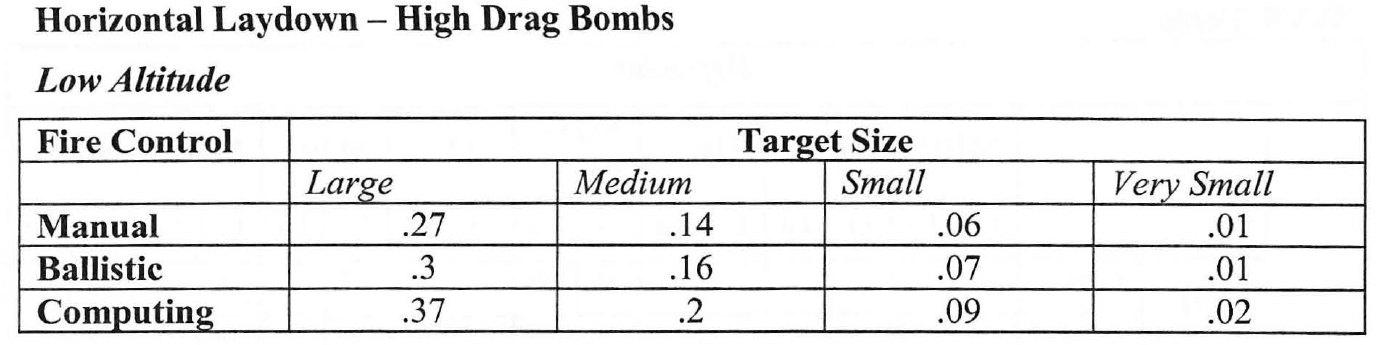

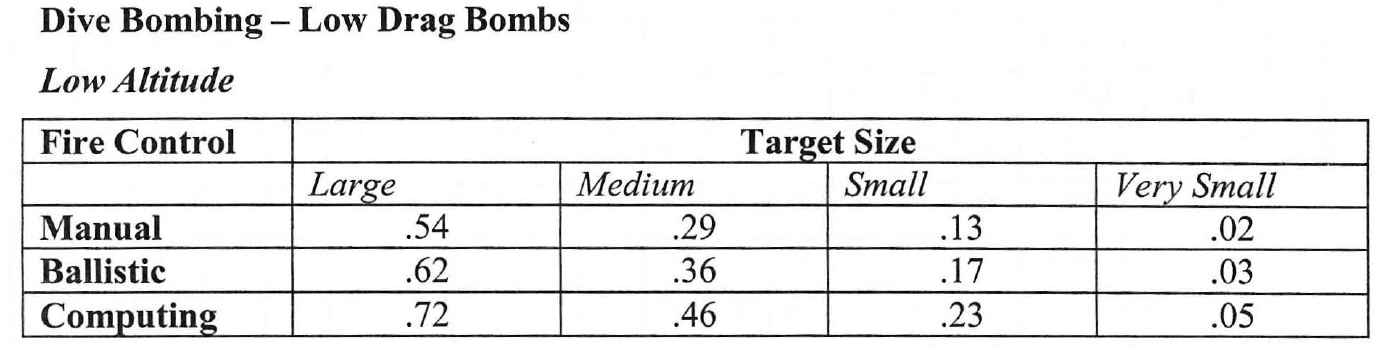

Charts such as these were essential tools in running the exercise, but were simple to use, while imparting fundamental knowledge to the students during play.

Charts such as these were essential tools in running the exercise, but were simple to use, while imparting fundamental knowledge to the students during play.

Eventually, however, we decided to move on to another shot at the Falklands War with a completely new approach.

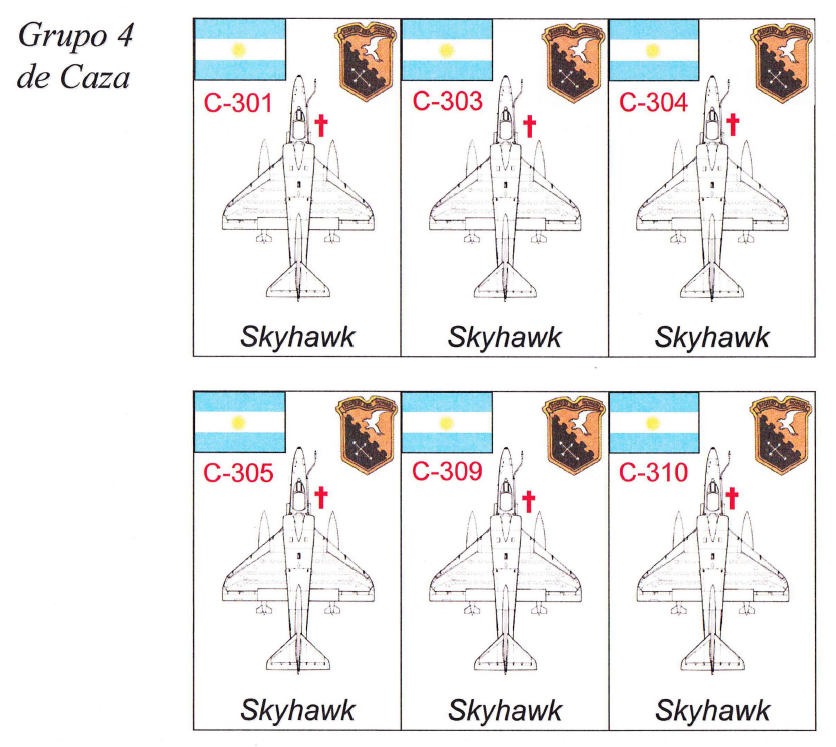

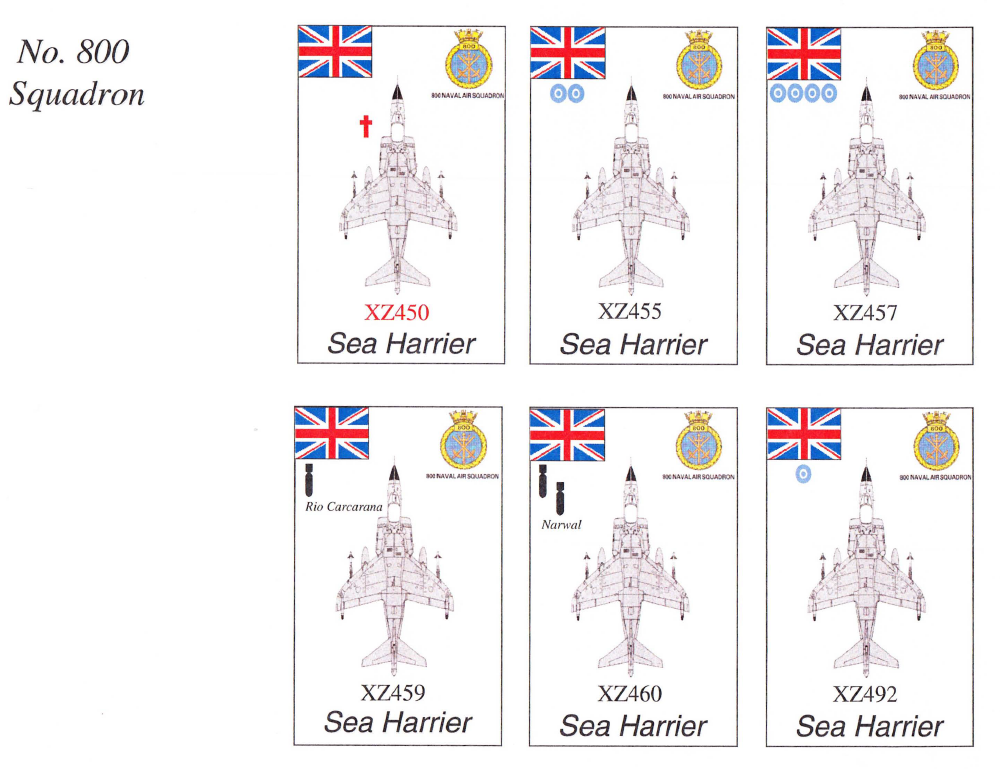

My initial attempt at making counters for the Falklands Air PE were both aesthetically pleasing and informative. Each card represents a single No 800 Squadron Sea Harrier. XZ450 was shot down (red aircraft number) and its pilot was killed in action (red cross), while XZ457 was the highest scoring aircraft of the conflict with four victories (this is an aggregate score of the multiple pilots who flew the aircraft).

My initial attempt at making counters for the Falklands Air PE were both aesthetically pleasing and informative. Each card represents a single No 800 Squadron Sea Harrier. XZ450 was shot down (red aircraft number) and its pilot was killed in action (red cross), while XZ457 was the highest scoring aircraft of the conflict with four victories (this is an aggregate score of the multiple pilots who flew the aircraft).

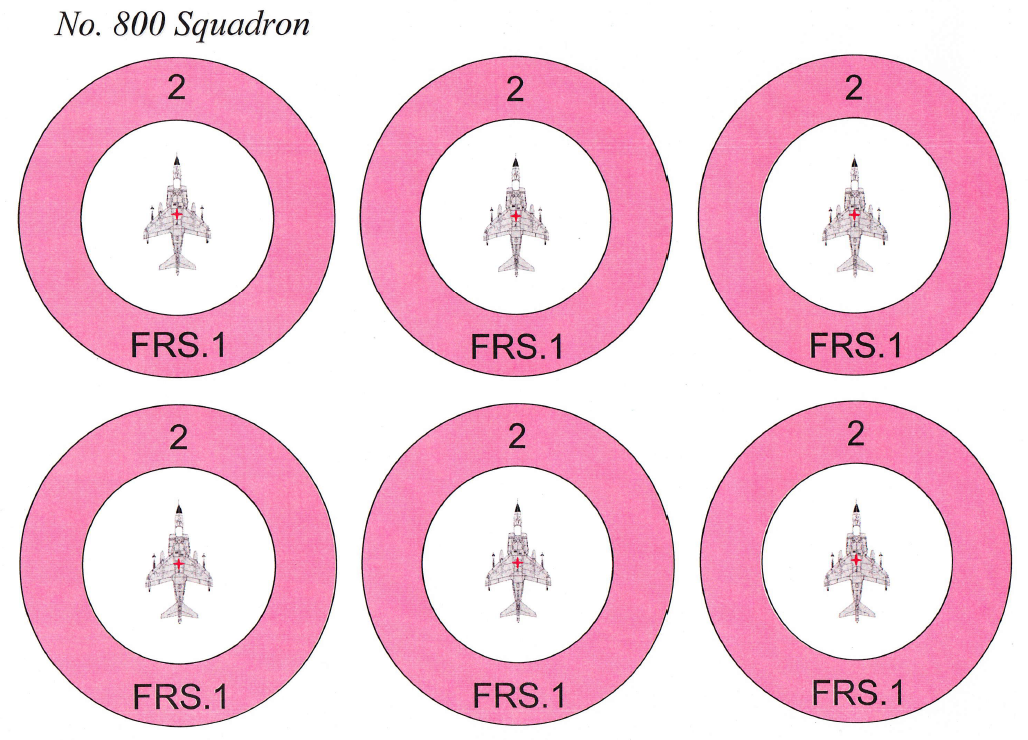

Eventually, we settled on a more practical, if less aesthetically pleasing, solution. The circles represent a practical limit on the distance a pilot can spot an enemy fighter-sized aircraft (about five miles) and were scaled to the aeronautical chart we used as a mapboard. The number represented the number of aircraft in the flight and would be marked off as aircraft were lost in combat. The counters were printed on clear plastic so one could easily see if the enemy aircraft’s location cross (centered on the aircraft illustration, in red) was inside the “dogfight circle” of an enemy aircraft. If so, it was, “Fight’s on!” An elegant solution, if I do say so.

Eventually, we settled on a more practical, if less aesthetically pleasing, solution. The circles represent a practical limit on the distance a pilot can spot an enemy fighter-sized aircraft (about five miles) and were scaled to the aeronautical chart we used as a mapboard. The number represented the number of aircraft in the flight and would be marked off as aircraft were lost in combat. The counters were printed on clear plastic so one could easily see if the enemy aircraft’s location cross (centered on the aircraft illustration, in red) was inside the “dogfight circle” of an enemy aircraft. If so, it was, “Fight’s on!” An elegant solution, if I do say so.

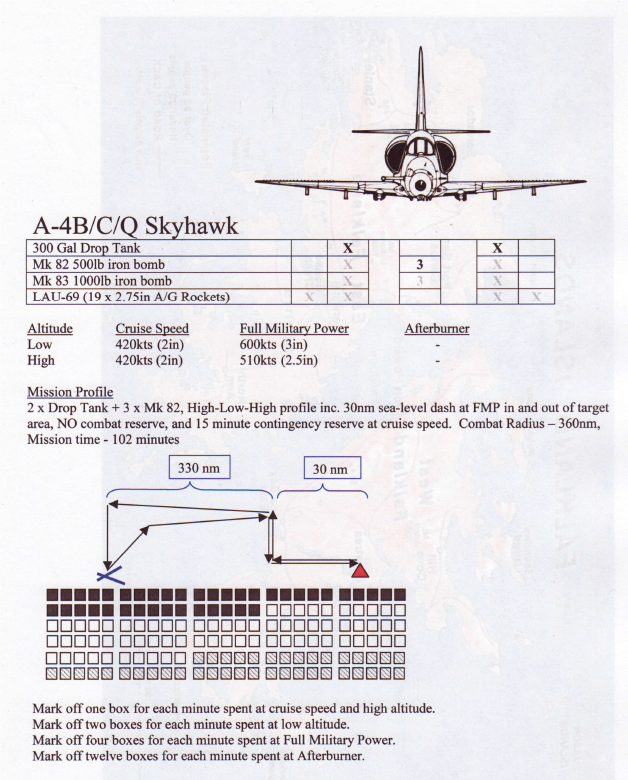

Additionally, the students had information on their own aircraft, which allowed them to plan their missions. At the top was a chart of possible loadouts with performance data below that. The Mission Profile was predicated on the real geography of the conflict between mainland bases and targets in the Falkland Islands. The black boxes on the fuel check-off chart represent fuel expended off-map on the way out to the target. The grayed-out boxes represent the same, only on the trip home. The students could expend fuel according to their judgment while using the white boxes, but had to fly off the edge of the map by the time the first gray box was checked off. The instructions were generic: the A-4 did not have an afterburner, as indicated in the performance section.

Additionally, the students had information on their own aircraft, which allowed them to plan their missions. At the top was a chart of possible loadouts with performance data below that. The Mission Profile was predicated on the real geography of the conflict between mainland bases and targets in the Falkland Islands. The black boxes on the fuel check-off chart represent fuel expended off-map on the way out to the target. The grayed-out boxes represent the same, only on the trip home. The students could expend fuel according to their judgment while using the white boxes, but had to fly off the edge of the map by the time the first gray box was checked off. The instructions were generic: the A-4 did not have an afterburner, as indicated in the performance section.

I am a firm believer that this kind of wargaming imparts more knowledge than all the lectures and books one could possibly assign. Having to assimilate information and use it to make decisions — particularly in a competitive environment — drives lessons home like nothing else. Our student critiques after our first (and only) running of this version proved this to be the case.

Immediately afterwards, the Kent School management decided to reorganize IMAC and use professional staff to teach the course, as opposed to analyst volunteers, so my association with teaching new analysts ended. I don’t know if they continued the use of our practical exercises, but I got the impression that this was one of their bones of contention — they simply didn’t see the relevance of wargaming.

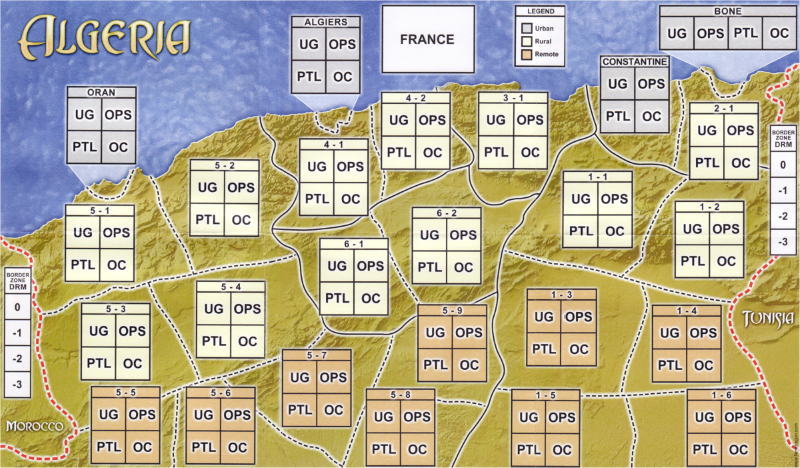

Fortunately, the manager of the Counterinsurgency course did. In fact, before he contacted our cadre of wargame instructors, Charles was already working on a practical exercise of his own. He had run across the commercial wargame Algeria, and went so far as to contact the designer and seek his help in adapting the system for our use. We worked for quite a while to trim down the game to something that could be taught and played in a single afternoon, while still teaching the lessons we wanted the students to learn.

The original map for Algeria.

The original map for Algeria.

We did quite a few runnings of the Counterinsurgency PE, and it usually came down to a three (and rarely, four) turn game. With one instructor at each table of four students — two to a side — the first turn usually involved some fumbling around, but the second ran more smoothly, and the third was usually very productive. Student critiques were almost always positive and in the “hot-wash” sessions after the exercise was over, the students were usually very positive about the PE driving home the principles that they had learned in class. Many had “ah, ha!” moments.

Over a 28-year career in the Intel Community at two different agencies, there is no question in my mind that the use of wargames in training is a true force multiplier. Not only did the students put theory into practical application and witness the outcomes of their actions, they had to think about how to use their assets in particular situations as opposed to dealing with hypotheticals and generalities. We opened the eyes of an entire generation of analysts who are now running the IC. Hopefully, they appreciate the education we gave them and are perpetuating the lessons they’ve learned.

——————-

Chip: “When ground forces actually came into contact, I simply drew a ratio and gave the students the results: at ≤1:1, the students were rebuked for making a bad attack and were told to bring up reinforcements or abandon the effort. At less than 3:1, the students were merely advised to bring up reinforcements and try again, and at 3:1 or greater, the battle was a clear-cut victory and the British ground forces commander won appropriate kudos…”

-This is an old T.D.N bugaboo. I don’t think the Brit’s ever have a 3:1 or better numerical superiority over the Argentinians. I understand that the exercise is supposed to teach broad principles, rather than be a precise simulation of (1980s) combat, but still…

I didn’t say, “numerical superiority.” The whole point of the QJM/TNDM approach is to use qualitative measurements, NOT merely quantitative. Further, the idea that the Brits fought outnumbered and won is pure propaganda. At Goose Green, the force ratio was little better than 1:1, but the outcome showed that — it took the Paras two days and a lot of casualties to force the surrender of a shambles of a defense garrison made up in large measure of Air Force cadets with almost no training.

Mt. Longdon was another hard fight where 3 Para made a frontal assault where they thought they were taking the Argentines in the flank. The reinforced Argentine company was able to slow the Paras, but could not prevail. Two Sisters and Mt. Harriet were manned by a single company, each and were assaulted by entire RM Commandos (battalions). Both of these high-odds ratio attacks succeeded brilliantly. Mt. Tumbledown was a Company position attacked the wrong way by the Scots Guards. They took more time and casualties than the Marines had, but still carried the hill. Wireless Ridge was the only battle that was fought by a blooded force. 2 Para took on this company position with all their lessons learned and swept the Argentine troops aside like they weren’t even there.

You will note that with the exception of Goose Green, each of the British assaults were made by a Battalion on an Argentine company position: essentially, a 3:1 numerical superiority.

The methodology I was describing was an expedient designed to teach the students without boring them at the end of a long exercise. I have run the campaign through Dupuy’s system many times since then and it formed a major case-study in my first Master’s thesis. It resolves the battles with a fidelity to history that is incredible, duplicating the casualties and time factors with tremendous accuracy.