Second to three recent articles from William (Chip) Sayers. The conclusions are his:

———-

The Easy Button

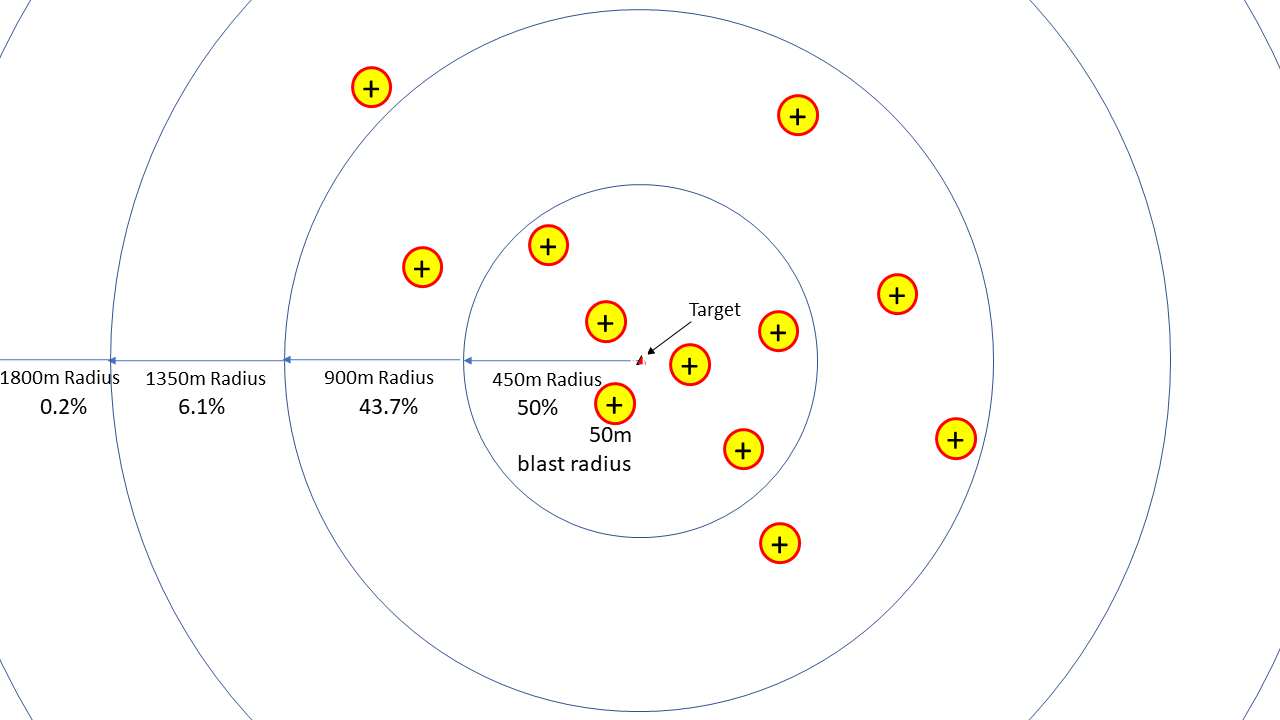

In the 1960s and 70s, the Soviet Union began exporting tactical and short-range ballistic missiles to its client states around the world. These missiles were developed as nuclear warhead carriers, so why give them to, for instance, Egypt, Iraq and North Korea? None of the countries were developing nuclear weapons, and Moscow wouldn’t have wanted these wild cards to do so at the time. All of these missiles had conventional warhead versions, and that’s what the Soviets were exporting, but they were so inaccurate as to make them virtually useless in the eyes of Western military analysts. A Soviet Combined Arms or Tank Army had three battalions of four R-17 Scud B launchers in their Table of Organization and Equipment, and they provided the army commander with a dedicated and powerful nuclear weapons capability. However, with a Circular Error Probable of 450m, twelve rockets with 1,000kg conventional warheads were highly unlikely to put even one within the effective blast radius of a point target.[1]

According to probability theory, half of the warheads would land within the CEP radius of the system, 93.7% within 2 CEPs, 99.8% within 3 CEPs and the balance within 4 CEPs. The Scud’s warhead can damage reinforced concrete buildings within an area of 7,854m2, compared to the 450m CEP which encompasses an area of 636,172m2. The Mean Area of Effectiveness (MAE) of the six warheads combined only cover about 7% of the total area of the CEP circle — not particularly promising odds for hitting a point target.[2]

While Western eyes would see this as a waste of time, the Soviets (and now the Russians) would look at it differently. The “War of the Cities” during the Iran/Iraq war — when the two sides used short-range ballistic missiles to indiscriminately bombard each other’s urban areas — offers considerable insight into the current war in Ukraine. The accuracy of the Scud B was obviously insufficient for most military targets. In this case, however, entire cities were the targets — as they are, today. Between 1984 and 1988, Iraq and Iran exchanged attacks on each other’s major population centers with fixed-wing aircraft, Tactical and SRBM attacks in a campaign of what can only be called Douhetian strategic bombing. The target for both sides was not military or industrial infrastructure, leadership or command/control capabilities. It was quite simply the enemy’s people. The aim was to inflict as much pain and destruction as possible on them to destroy their will to continue the war. While thousands of civilians were killed and wounded (Iran admitted to over 10,000 deaths, alone), both country’s efforts seemingly failed.

However, it is never easy to say for sure what the impact is of operations aimed at influencing the enemy’s psychology. All of warfare is essentially intended to get inside the enemy’s head, be it via influence operations or sheer destruction of the enemy’s forces. Campaigns rarely, if ever, end in annihilation — at some point, the enemy’s will is broken and he gives ground or surrenders. For example, it is a myth that the strategic bombing of Britain, Germany and Japan during WWII was counterproductive, resulting in a strengthening of the public’s desire to resist the attackers. In fact, in all three cases, public morale declined substantially and industrial production was suppressed even in factories that were not bombed. Defeatism and absenteeism soared. Britain was not subjected to an effective and sustained campaign, but in Germany and Japan it is likely that their respective secret police forces were the major factor in keeping a lid on a possible revolt of the kind that resulted in the withdrawal from fighting by Russia and Germany in WWI.

Neither Iraq, nor Iran had the wherewithal to mount a sustained campaign — a small inventory of weapons on both sides ensured that the war of the cities could only be fought in fits and starts — nevertheless, Tehran was reportedly so damaged in the last months of the war that as many as 1 million of its 6 million residents left the capital city. There was also a great deal of fear that Iraq would start arming its Scuds with chemical warheads — a particular terror for civilians with no access to protective equipment. It is uncertain how much influence the war of the cities had on the mind of the Ayatollah or the Majles, but between that, a rejuvenated Iraqi Air Force and battlefield reverses, Ayatollah Khomeini was moved to “drink the chalice of poison,” and agree to end the war.

In 1995, the Russians went full scorched earth in Grozny, though their purpose in razing the city was tactical, rather than strategic: they used it as a tactic for clearing the city of insurgents, not breaking the will of the Chechen people and leadership. The results were much the same for the city, however.

Fast forward to the current war in Ukraine. When their coup de main on Kiev failed, the Russians fell back on their old tricks of attempting to flatten cities to demoralize their enemies into submission. And that’s where things stand, today.

For the last thirty years, the Russians have talked up the accuracy of their tactical and short-range ballistic missiles, referring to them as precision weapons. Russian claims notwithstanding, photos of Ukrainian cities show plain evidence that civilian residences and infrastructure have suffered massively from the besieger’s bombardment. Entire neighborhoods of apartment buildings are rubbled and burned out. The Russians claim this to be collateral damage, but if the Russian missiles have “pin-point” accuracy, that shouldn’t occur on such a scale as this. The implication is that the apartment complexes, schools and hospitals are the targets. Deliberately targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure is a war crime. On the other hand, if the accuracy of Russian missiles is so poor that it takes this much destruction to hit legitimate targets, then the bombardment is indiscriminate, and that is a war crime, too. Either way, Western governments should drop the pretenses and treat Putin as what he is: a war criminal.

This begs the question as to why Putin is using such weapons to prosecute his war. To put it bluntly, he can’t trust his Air Force to do it. Russian fixed-wing bombers are not sufficiently accurate, their crews are not sufficiently well trained, and they are too vulnerable to Ukrainian air defenses to be survivable. So, they are stuck with delivering stand-off missiles from the safety of Russian territory. Again, these weapons are claimed to have great accuracy, but there is little evidence to back up these assertions.

So, what’s going on here? Why all the seeming contradictions? There are three possibilities. First, Russian missiles just aren’t that accurate and they’ve been making false claims in order to boost arms sales. This is probably the likeliest explanation and fits well with the possibility that they are using relatively low-cost munitions to bombard Ukrainian cities. Second, the Russians may be pressing into service high-precision and expensive missiles in a role they are ill-suited for. To wit: they are dumbing-down or removing their guidance systems to allow for a more traditional random bombardment — an expensive way to do the job. Third, the Russians are really hitting what they are aiming at with great precision. Apartment buildings are being targeted as though they were factories with specific aimpoints chosen to make for maximum destruction.

In the months prior to D-Day in June 1944, Gen. Eisenhower directed that all Allied heavy bombers in theater target railroad marshalling yards in France and Belgium to hinder the ability of German reinforcements to make it to the lodgment area. USAAF commanders believed their bombers could make a better contribution to success by bombing strategic targets in Germany and offered the fact that they couldn’t prevent French and Belgium casualties, given that marshaling yards tended to be located near the city centers. Eventually, the French and Belgian governments in exile authorized the strikes, believing the good they did would outweigh the civilian deaths they would cause, and while there is some question on how effective the strikes actually were, they caused much less collateral damage than had been feared. If Russian missiles are simply inaccurate and the proportion of collateral damage was reasonable compared to the damage caused to legitimate military targets, their actions might be seen as justifiable. However, the damage to civilian areas clearly isn’t reasonable. Further, tampering with guidance systems or the deliberate targeting of precision weapons against civilian targets would be evidence of a coldly calculated crime. The Hague should be warming up a cell for Mr. Putin.

The intriguing train of thought from this problem, however, is what happens next with precision-guided missiles? The US GMLRS, HIMARS and ATACMS systems have long proven that surface-to-surface missiles with GPS guidance can strike with great precision with relatively little technical investment. While their Russian counterpart systems have not, for whatever reason, shown this level of accuracy, it is clear that Moscow’s weaponry should be able to do so, if not now, certainly in the near future. It is simply not that difficult to do. Iran has claimed to have achieved a 50m CEP with some of their SRBMs. While this is, perhaps, a dubious assertion now, it is inevitable that nearly every nation that desires so may have access to weapons of such range and accuracy at some point in the near future. What are the implications? Several come to mind.

- From the illustration above, it is easy to see that a Scud-sized warhead with a 50m CEP would virtually guarantee target destruction when two are fired at a single target. The commander presses a button and the target goes away. While high-precision SRBMs may be relatively expensive, they are a bargain for a country without a first-class air force.

- This is in contrast to dependence upon an indifferently trained aircrew with elementary tactics, obsolescent weapons and aircraft having to penetrate lethal air defenses before making a low-probability of success attack. SRBMs don’t get scared or refuse a mission because of difficult circumstances, or because they disagree with their political leadership. The necessity of training and maintaining an expensive and unreliable air force is eliminated, as well — at least with regard to the air-to-ground mission. A similar savings could be made by substituting Surface-to-Air missiles for fighter-interceptors in the air-to-air role.

- The ensuing cost to success ratio is likely to tempt the use of high-precision ballistic missiles to solve problems that otherwise might be addressed through diplomacy, economic pressure, or other means short of violence. One could easily envision even policing actions being undertaken through the use of missiles: a wanted criminal or political adversary is located taking sanctuary in a nearby uncooperative country, the leadership doesn’t waste time arguing about extradition, he presses his “Easy Button” and obliterates the residence the wanted fugitive is occupying. Problem solved. An economic rival is pumping too much oil for your taste? Press the Easy Button and make some unmanned pumping stations go away. Problem solved. A rival’s fishing fleet encroaching in your exclusive economic zone? The Easy Button makes some trawlers mysteriously disappear in the night and the problem is solved.

While it is easy to come up with dozens of scenarios where precision married to long-range weapons can be useful, the difficult part is developing a useful doctrine to employ them to maximum effect. Destroying a group of targets will have an impact, though limited to the additive effect of their individual values. Destroying the same number of targets according to an effective and well thought-out plan will have multiplicative effect far beyond the value of the individual elements. The whole will be much greater than the sum of its parts. What is required is an airpower doctrine — missile warfare is the purist, most fundamental form of airpower. However, there is only one military force in the world that has thoroughly explored airpower doctrine and that is the US Air Force.

The only countries with the elements required to develop a viable airpower doctrine (a truly independent air force, an air force of sufficient size as to explore and test ideas while continuing to meet defense obligations, an academic plant of sufficient independence to develop suitable doctrine, an industrial base capable of designing and manufacturing the necessary tools, etc.) are all strong allies of the US, and none of them has an air force of sufficient size to realistically execute such a doctrine on their own. None of our adversaries has those elements necessary to do so, so it is likely that whatever precision ballistic missile attacks they execute will be done so with suboptimal, less than decisive effect.

The upshot is that without a vital, robust and well-founded doctrine, these weapons will not be capable of fulfilling their potential, but will rather merely become long-range artillery. They may be capable of great destruction, they are unlikely to ever become decisive unless wielded with an educated hand.

The Japanese Navy began World War II with an excellent submarine fleet armed with a revolutionary torpedo that actually worked, unlike those of virtually every other navy. In contrast, the US Navy fielded obsolescent boats (albeit, with superbly trained crews) armed with virtually worthless torpedoes. Over the course of the war, the US submarine service proved decisive in the defeat of Japan by cutting off Japanese transport of vital resources and troops to the home islands. The Japanese submarine force, by contrast, contributed very little to the overall war effort. The difference was doctrine. The Japanese wasted their assets on scouting for their battleline, while virtually ignoring the US lines of communications that ran across vast stretches of ocean. US submarines interdicted Japanese LOCs — vital for linking the home islands with the natural resources they went to war over in the first place.

If someone manages to marry the new, high-precision SRBMs with a solid, well thought out doctrine, we will move from an age of warfare where missiles are used, to a true age of missile warfare. That would be a real “revolution in military affairs.”

[1] Missile Defense Project, “SS-1 “Scud”,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 11, 2016, last modified August 2, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/scud/.

[2] Weapon Data Fire Impact Explosion, Final Edition September 1945, Osrd No. 6053, Division 2, National Defense Research Committee Office Of Scientific Research And Development.

——–

P.S.: Some related past posts:

VVS View of Air Superiority | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org)

“but in Germany and Japan it is likely that their respective secret police forces were the major factor in keeping a lid on a possible revolt of the kind that resulted in the withdrawal from fighting”

For Germany this is not true, the Gestapo was actually surprised how low the impact of allied bombing on morale was. This topic is covered in serious German historical literature, e.g. Volume 6 “Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg. There was no danger that allied bombing would have led to uprising of population or soldiers. One gets the impression that personal opinion is used as substitute for hard data.

Strategic bombing started in 1940/41 by the Bomber Command, the first years it had no impact, it was often not even clear, which the intended traget was because of the unability of the bomber crews to find the assigned targets.

And the impact on industrial prduction was often not very strong, even refineries were not knocked out for longer periods of time in 1944 despite of bombing raids with very high intensity. The repair crews became vere efficient and had low losses. Sometimes allied bombing was used as excuse for other screw up of the industrial management. Bombing did damage but it was not the game changer.

And the main issue with strategic bombing is of course opportunity costs. Do you really believe that the heavy bomber used by the RAF in 1941-1943 would not have had a higher impact fighting Uboote instead of getting decimated over German cities without really doing high damage? Harris was told by his own OR guys about the low impact of the first 1000 bomber raids in 1942, that with unsustainable losses. The attacks were good for morale in UK but not really a wise investment against Germany.

The Patriot, which was initially designed against aircraft has a really long range and high ceiling. One wonders if their introduction was as much to keep the Russians from flying really high and just carpet bombing cities.

Visa vi WW2, the RR attacks were devastating. I am reading about the fighting around Calais in the immediate aftermath of Goodwood. The Germans have to go to extreme measures to get one RR line to the area operational.

https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/0807rails/

Note the part about the wonders of Rommel and his anti-DD plan are bit debatable.

Posted too quick. The assessment of WW2 Strategic bombing has been reassessed again. The current thinking, and what should always have been obvious, is that it had a huge economic effect.

One illustration: The US and Germans had roughly the same number of people working at building air craft. Look at the production figures. The difference is that the US built factories that were absolutely enormous, while the Germans had to spread theirs around all over the place, often underground.