This is another piece of TNDM analysis from William (Chip) Sayers. He will be doing a presentation at our Historical Analysis conference: Who’s Who at HAAC – part 1 | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org). Now, I have questioned the Ukrainian estimates of overall casualties: The Ukrainian casualty claims are inflated – part 1 | Mystics & Statistics (dupuyinstitute.org). This post by Chip Sayers makes the point that the estimates of 400+ Russian casualties in this river crossing operation is believable.

The William (Chip) Sayers piece:

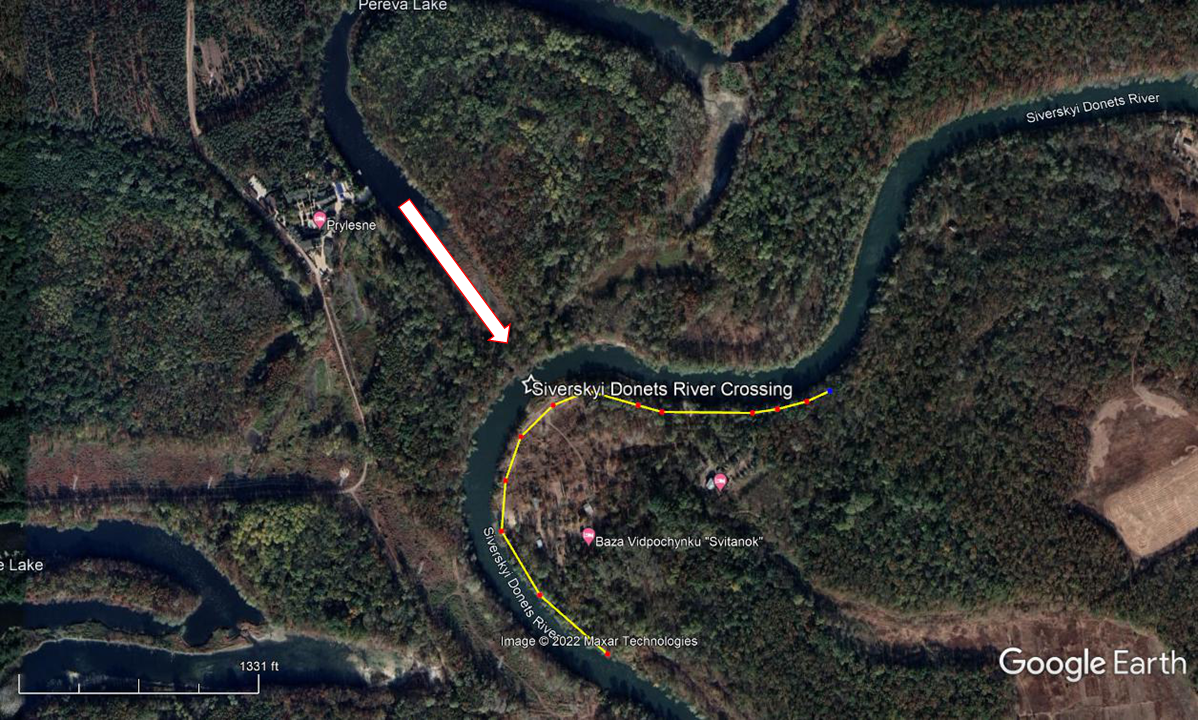

The objective of this set of model runs was to explore the failed Russian river crossing operation of the Siverskiy Donets. Ukrainian photos of the battlefield aftermath showed vividly the carnage wrought by modern defenses when properly warned and deployed.

Ukrainian reconnaissance detected the Russian preparations to cross the Siverskiy Donets at least 3 days prior to the river crossing operation, which gave them time to bring up reinforcements and prepare a defense. According to uawardata.com, The 79th Ukrainian Air Assault Brigade was defending the sector, while one or two Battalion Tactical Groups from the 35th and 74th Mechanized Brigades of the 41st Combined Arms Army were in the area of the attack. The Institute for the Study of War reports that it was a BTG from the 74th Mech Brigade that conducted the attack.

The vulnerability of attacking forces in a river crossing operation is such that surprise and support are necessary to preclude catastrophic losses. Clearly, the Russian BTG failed to achieve surprise — it is unknown how well supported they were, but the scale of their losses indicates that whatever support they had was probably inadequate.

I set up the battle with the following forces:

Russian: one mechanized BTG from the 74th Mech Brigade with support from half the guns of the 120th Artillery Brigade (the 41st CAA’s sole artillery brigade) and 30 Mi-24 attack helicopter sorties.

Ukrainian: one battalion from the 79th Air Assault Brigade plus a battalion slice of brigade assets (the brigade apparently was covering a large frontage and probably couldn’t afford to devote more to the battle). Assuming the Ukrainian Army productively used the warning time they had to bring up supporting fires, I gave the defenders an Urgan MRL battalion from the 27th Rocket Artillery Brigade. Just for fun, I also gave them ~10% of the Switchblade “kamikaze” UAS that the United States has sent (100 x Switchblade 300 anti-personnel drones and 20 x Switchblade 600 anti-tank drones).

The Siverskiy Donets is only about 50m wide at the crossing point, and the ground is heavily forested, though relatively flat. As best as can be determined from aerial video imagery, the battlefield is actually too small to support an attacking battalion. Soviet motorized rifle battalions attacked on a minimum frontage of 1 kilometer, while a Russian BTG is somewhat beefier organization. The Siverskiy Donets makes a partial loop at the point of attack and a kilometer attack zone would have taken the entire frontage of the loop such that Russian troops on one side might have been firing into the faces of their compatriots attacking at the other end of the line. This suggests that they probably attacked on no more than a single company frontage (400m), with four companies in echelon. This is not a formula for success in an opposed river crossing.

For the base case, I did not give the Ukrainian side a CEV advantage, nor surprise to either side.

Results:

After a full day of battle on 11 May, the Russians were decisively repulsed, having lost 27% of their personnel, 80% of their armored fighting vehicles, 50% of their attack helicopters and 38% of their overall combat power. This compares favorably to the ISW’s estimate of 458 casualties (the TNDM predicted 521) and 80 pieces of equipment, compared to the TNDM report of 89. 50% losses to the attack helicopter force is probably a bit overstated and could bear closer examination.

In contrast, the Ukrainians lost 6% of personnel (85 men), 2 AFVs and 6% of their combat power.

This disparity in the loss of combat power to the two sides would have undoubtedly made another attempt to cross the river on the 12th a non-starter, even though some sources have reported it as a two-day battle. If these losses are indeed indicative of what really happened, the second day’s attack could only have been carried out by the 35th Brigade’s BTG. This would imply that not one, but two BTGs may have been wrecked in the Siverskiy Donets operation.

Run #2: While the force-to-space ratios don’t really support at two-BTG attack, it is possible that when the 74th Mech’s BTG was rendered combat-ineffective, the 35th’s BTG was passed through the 74th to renew the attack. By including both BTG’s in the Russian Order of Battle and throwing in the balance of the 120th Artillery Brigade, we can see the impact of a rough 2:1 numerical advantage for the attacker’s side.

As it happens, even this reinforcement only yielded a combat power ratio of 1:1, which did not allow for a successful crossing of the river. Russian casualties were somewhat lower, but still higher than the defender’s losses. Both sides took about 7% personnel losses, but the Russian units had roughly double the personnel, so took 271 casualties as opposed to only 110 by the Ukrainians. The Russians lost 29 AFVs to the Ukrainians’ 3, but this is deceptive as the defenders had only a small number of tanks to lose — their 3 AFV losses represented 45% of their starting force. The bigger story is that the Russian’s lost 15% of their combat power, while the Ukrainians lost just 8%, thus ensuring the attackers would never make it across the river without significant reinforcement.

Run #3: Some sites have reported that the operation continued into a second day, so the third run was essentially the first run with a second day’s extension where the 35th Brigade’s BTG took over the fight. I also postulated that it would be too expensive for the Ukrainians to devote a second package of Switchblade drones to battle. Therefore, the defenders’ combat power was weakened in comparison to the first day’s battle, despite their low losses.

After extracting the losses to the defenders and not adding the Switchblade package back in, the fresh 35th Bde BTG replaced the broken 74th’s BTG with exactly the same combat power. Thus, we have a fresh second echelon committed to battle against a moderately depleted defender.

Results:

Without their Switchblade drones, the 79th Air Assault Brigade defenders were unable to repulse the second echelon, though the attack was only able to make 350 meters beyond the river’s edge. In doing so, the Russians lost another 323 men, a third of their AFVs and 14% of their combat power. The defenders lost 130 men, 2 AFVs and 1% of their combat power. All told, in the two-day battle the Russians lost nearly 850 men, 45 AFVs, had one BTG rendered combat ineffective and barely gained a toehold on the south side of the Siverskiy Donets.

Run #4: Clearly, a CEV advantage to the Ukrainian side would merely make the Russian defeats in Runs #1 and #2 worse, so they needn’t be explored further. Run number 4 was run as run #3, but with a Ukrainian CEV of 1.2.

Results:

On day 1, the Russians lost 57% of their combat power and 124% of their AFVs, indicating they their armored vehicles wouldn’t have survived to the end of the day, thus the battle would have likely ceased less than 16 hours in. After such a slaughter, it is questionable if the Russians would have tried it again the next day with the second BTG.

On day 2, the Russian second echelon managed to take the crossing site to the same depth as run #3, but lost 50% of their AFVs and 20% of their combat power in doing so. The casualty list after two days would have totaled over a thousand Russian soldiers. Technically, this might be called a Russian “victory,” but without a substantial exploitation force behind them, it would surely be a pyrrhic one.

Run #5: The next few runs explored the idea that the Russians not only failed to achieve the needed surprise, but were, in fact, surprised by the resistance they ran into. Again, runs #1 & #2 were sufficiently adverse to the attacker that they needn’t be explored further. This is a re-run of run #3 with minor surprise by the defenders.

Results:

While the 74th’s BTG was thoroughly destroyed (41% personnel losses, 161% of AFVs and 71% of its combat power lost), interestingly, the 35th’s BTG made the same gains and losses were almost exactly what they were in run #4. This surprising result is because surprise degrades over time, and the second day of minor surprise essentially equates to the Ukrainian CEV of 1.2 from run #4.

Run #6: Given this, run #6 was done with substantial surprise. Not surprisingly, the 74th BTG was obliterated in short order, losing over 54% of its personnel, 271% of its AFVs and 115% of its combat power. It could be scratched out of the Russian OOB after half a day’s fight. The 35th BTG, however, still made it across the river, albeit at some cost.

Run #7: Run 7 was done with complete surprise — not a likely situation, but one explored for completeness. The results were much the same, with the 74th annihilated after just a few hours, while the 35th persisted in gaining the far bank of the Siverskiy Donets. However, at a cost of 1/3rd of its personnel, all of its AFVs and 35% of its combat power, the BTG would have been hors de combat until a rest and refit period were accomplished.

At this point, I ran several sensitivity exercises without using the Switchblade package from the first day of the battle, but including variations of surprise and CEV. No amount of surprise was capable of repulsing the attack and only a Ukrainian CEV of 1.5 proved sufficient to keep the Russians on their side of the river without the use of the kamikaze UAVs. As a large influx of combat power in some form was needed to rebuff the attack, I made a final run with the entire 79th Air Assault Brigade in place of the Switchblades. This did, indeed, defeat the single BTG on day 1 of the battle with losses comparable to those estimated to have actually been incurred by the Russian force. In other words, it took a force three times the size of our estimate to successfully defeat the river crossing without extraordinary support. This would, of course, have been advantageous for defending a day 2 attack by the 35th BTG had it occurred, since the entire brigade would remain in place, as opposed to the Switchblade package that we posited would be too expensive to recreate for the second day’s battle.

Conclusions:

Once again, the TNDM has demonstrated that the reported results of this battle are entirely consistent with historical outcomes — nothing too unusual or particularly remarkable happened here.

Also, Russian tactical incompetence is once again the key to interpreting the results of this battle. Had the Russians achieved the prerequisite surprise, things would have gone very differently. A final model run with the shoe on the other foot confirms this.

Finally, the impact of a single weapon system — in this case the Switchblade kamikaze UAS — proved pivotal. Essentially a round of ammunition, these killer drones significantly boosted the combat power of the defenders. However, once expended, the defending units went back to their organic firepower, which was insufficient to hold the line. This underscores the importance of a steady, sustainable supply of weapons and logistical support from NATO and other countries sympathetic to the Ukrainian cause.

How are you rating the switchblade systems ?

Mad Dog

We did not do the analysis. Chip Sayers, a retired analyst, will have to get back to you this. I did post the following link on twitter related to a question about Switchblades: https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3027295/fact-sheet-on-us-security-assistance-for-ukraine/

I’ve been asked two questions about my blog post of June 8th. The first is, “How do you know the Ukrainians use the Switchblade UAS in the Siverskiy Donets river-crossing operation?” The second was, “How did you score the Switchblade?”

First off, we’re operating off of some very thin data and I don’t know what the Ukrainian forces employed. They had time to shift forces and that may have included some of their shiny new toys from the West, but at this point, we really don’t know. I decided that this would make an excellent test case for measuring not only the effectiveness of having a forewarned, competent force defending against a not-so-competent force in a river crossing operation, but also the impact of some of these new weapons.

The model doesn’t care (much) what kind of firepower that is used to generate a weapon’s lethality index as the entire point is to make them fungible. In reality, there are some minor differences in how different categories of weapons are treated, but for the most part, weapons scores are treated the same, regardless of type. I could have given the Ukrainian side the balance of the Urgan brigade, or even a conventional tube-artillery brigade and gotten much the same results, but I specifically chose to test something that is used as a round of ammunition so that I could take them out of the experiment for the second day’s fight to allow a direct compare & contrast. Besides, looking into Switchblade would be fun.

There are four different ways the Switchblade’s Operational Lethality Index (combat power score) can be calculated: as an infantry weapon, an ATGM, an artillery weapon, or as an aircraft. There is no clear-cut answer to how its score it. The Switchblade 300 is an anti-personnel/light-materiel weapon that could be considered a long-range mortar within the confines of the model. Scoring it this way, the Switchblade 300 has an OLI of 220, while the block 10C, with 2 ½ times the range, has an OLI of 319. This compares to an AKM assault rifle at .16, an M-2HB .50 cal heavy machinegun at 1.2, or an M-43 120mm mortar at an OLI of 145.

The larger Switchblade 600 is primarily an anti-tank weapon and scoring it as an ATGM yields an OLI of 409. This compares well with the Russian Konkurs (113), Kornet-E (175), US TOW-2B (136) and Javelin-C (246). This is primarily due to the Switchblades much greater range. Scored as an artillery system — much like an MRL rocket or SSM — the Switchblade 300 Block 10C has an OLI of 151. This compares to the 227mm HIMARS MLRS at 338, or a Russian 9K720 Iskander SSM at 184.

The obvious course is to score it as a fixed-wing aircraft, but this is a bit trickier than it appears at first blush. Fixed-wing aircraft carry weapons, but in the case of the Switchblade, the aircraft is the weapon. So, I scored the warhead as the weapon, and had the “aircraft” carry one of these weapons. Then I gave the “aircraft” the characteristics of the UAS. This isn’t as easy as it looks, as both the “weapon” and the “aircraft” must have a range (in the case of the weapon) or a radius (in the case of the “aircraft”). For the weapon range, I estimated the range at which the UAS would lock-on to the target and begin to make its terminal dive. For the radius of the aircraft, I simply used the cruise speed times the UAS’ endurance which yielded a maximum range without any time for loiter (it might go a bit farther by bumping up to max velocity at the end of the flight, but I ignored that). I felt that the UAS’ loiter time was one of its defining characteristics, but that the model did not give direct credit for that, so I translated it into range. I believe that using a range instead of radius figure is correct as it more accurately represents the spirit of what the model is trying to capture. Doing business this way yielded an OLI value of only .76 for the Switchblade 300 Block 10C (approximately halfway between a medium and a heavy machinegun) and 5.34 for the 600, which would be less than 1/2 the score of the one-shot, 60-year-old US 66mm LAW. By comparison, the MQ-1 Predator UAS has an OLI of 161, while a MQ-4 Reaper scores a 933 OLI. Clearly, this does not adequately reflect the contribution of this unique and versatile weapon. Consequently, I decided to use the ATGM value for the Switchblade 600 and the infantry OLI for the Switchblade 300. It so happens that these are the highest values for the UAS, but I believe I can justify their use.

An interesting dilemna. Who could of seen this 20 years ago ?

Would you penalize the OLI score for the Switchblade for it being a 1-shot weapon ? More like an AT-4 than a Carl Gustav ? Can you reload the Switchblade launcher ?

Can the SB software prevent multiple SB from attacking the same target ?