[The article below is reprinted from October 1996 edition of The International TNDM Newsletter.]

Validation of the TNDM at Battalion Level

by Christopher A. Lawrence

The original QJM (Quantified Judgement Model) was created and validated using primarily division-level engagements from WWII and the 1967 and 1973 Mid-East Wars. For a number of reasons, we are now using the TNDM (Tactical Numerical Deterministic Model) for analyzing lower-level engagements. We expect, with the changed environment in the world, this trend to continue.

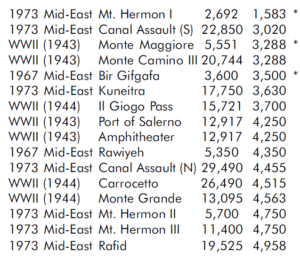

The model, while designed to handle battalion-level engagements, was never validated for those size engagements. There were only 16 engagements in the original QJM Database with less than 5,000 people on one side, and only one with less than 2,000 people on a side. The sixteen smallest engagements are:

While it is not unusual in the operations research community to use unvalidated models of combat, it is a very poor practice. As TDI is starting to use this model for battalion-level engagements, it is time it was formally validated for that use. A model that is validated at one level of combat is not validated to represent sizes, types and forms of combat to which it has not been tested. TDI is undertaking a battalion-level validation effort for the TNDM. We intend to publish the material used and the results of the validation in the International TNDM Newsletter. As part of this battalion-level validation we will also be looking at a number of company-level engagements. Right now, my intention is to simply just throw all the engagements into the same hopper and see what comes out.

While it is not unusual in the operations research community to use unvalidated models of combat, it is a very poor practice. As TDI is starting to use this model for battalion-level engagements, it is time it was formally validated for that use. A model that is validated at one level of combat is not validated to represent sizes, types and forms of combat to which it has not been tested. TDI is undertaking a battalion-level validation effort for the TNDM. We intend to publish the material used and the results of the validation in the International TNDM Newsletter. As part of this battalion-level validation we will also be looking at a number of company-level engagements. Right now, my intention is to simply just throw all the engagements into the same hopper and see what comes out.

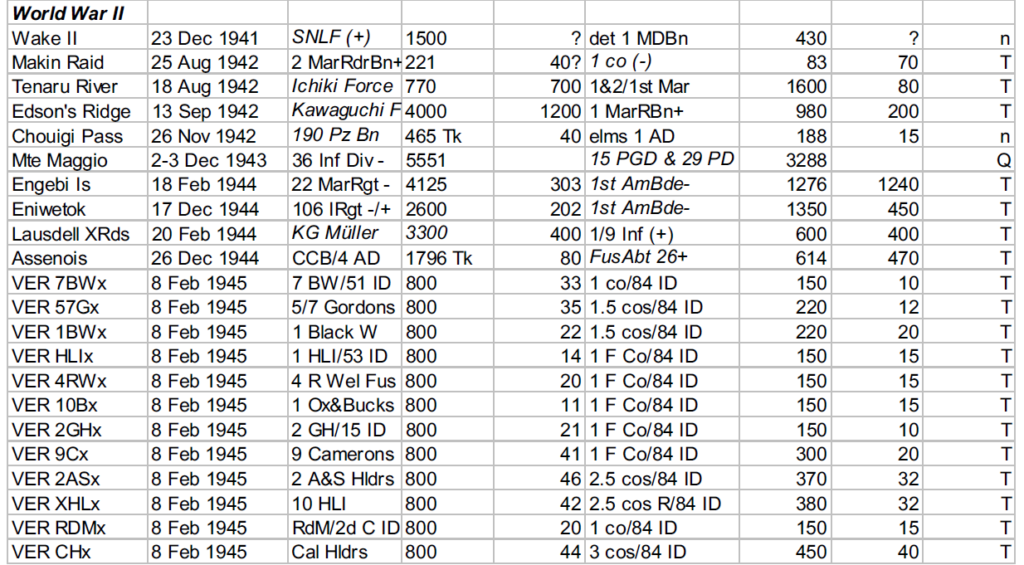

By battalion-level, I mean any operation consisting of the equivalent of two or less reinforced battalions on one side. Three or more battalions imply a regiment or brigade—level operation. A battalion in combat can range widely in strength, but that usually does not have an authorized strength in excess of 900. Therefore, the upper limit for a battalion—level engagement is 2,000 people, while its lower limit can easily go below 500 people. Only one engagement in the original OJM Database fits that definition of a battalion-level engagement. HERO, DMSI, TND & Associates, and TDI (all companies founded by Trevor N. Dupuy) examined a number of small engagements over the years. HERO assembled 23 WWI engagements for the Land Warfare Database (LWDB), TDI has done 15 WWII small unit actions for the Suppression contract and Dave Bongard has assembled four others from that period for the Pacific, DMSI did 14 battalion-level engagements from Vietnam for a study on low intensity conflict 10 years ago, and Dave Bongard has been independently looking into the Falkland Islands War and other post-WWII sources to locate 10 more engagements, and we have three engagements that Trevor N. Dupuy did for South Africa. We added two other World War II engagements and the three smallest engagements from the list to the left (those marked with an asterisk). This gives us a list of 74 additional engagements that can be used to test the TNDM.

The smallest of these engagements is 220 people on both sides (100 vs I20), while the largest engagement on this list is 5,336 versus 3,270 or 8,679 vs 725. These 74 engagements consist of 23 engagements from WWI, 22 from WWII, and 29 post-1945 engagements. There are three engagements where both sides have over 3,000 men and 3 more where both sides are above 2,000 men. In the other 68 engagements, at least one side is below 2,000, while in 50 of the engagements, both sides are below 2,000.

This leaves the following force sizes to be tested:

These engagements have been “randomly” selected in the sense that the researchers grabbed whatever had been done and whatever else was conveniently available. It is not a proper random selection, in the sense that every war in this century was analyzed and a representative number of engagements was taken from each conflict. This is not practical, so we settle for less than perfect data selection.

These engagements have been “randomly” selected in the sense that the researchers grabbed whatever had been done and whatever else was conveniently available. It is not a proper random selection, in the sense that every war in this century was analyzed and a representative number of engagements was taken from each conflict. This is not practical, so we settle for less than perfect data selection.

Furthermore, as many of these conflicts are with countries that do not have open archives (and in many cases limited unit records) some of the opposing forces strength and losses had to be estimated. This is especially true with the Viet Nam engagements. It is hoped that the errors in estimation deviate equally on both sides of the norm, but there is no way of knowing that until countries like the People’s Republic of China and Vietnam open up their archives for free independent research.

TDI intends to continue to look for battalion-level and smaller engagements for analysis, and may add to this data base over time. If some of our readers have any other data assembled, we would be interested in seeing it. In the next issue we will publish the preliminary results of our validation.

Note that in the above table, for World War II, German, Japanese, and Axis forces are listed in italics, while US, British, and Allied forces are listed in regular typeface, Also, in the VERITABLE engagements, the 5/7th Gordons’ action continues the assault of the 7th Black Watch, and that the 9th Cameronians assumed the attack begun by the 2d Gordon Highlanders.

Note that in the above table, for World War II, German, Japanese, and Axis forces are listed in italics, while US, British, and Allied forces are listed in regular typeface, Also, in the VERITABLE engagements, the 5/7th Gordons’ action continues the assault of the 7th Black Watch, and that the 9th Cameronians assumed the attack begun by the 2d Gordon Highlanders.

Tu-Vu is described in some detail in Fall’s Street Without Joy (pp. 51-53). The remaining Indochina/SE Asia engagements listed here are drawn from a QJM-based analysis of low-intensity operations (HERO Report 124, Feb 1988).

The coding for source and validation status, on the extreme right of each engagement line in the D Cas column, is as follows:

- n indicates an engagement which has not been employed for validation, but for which good data exists for both sides (35 total).

- Q indicates an engagement which was part of the original QJM database (3 total).

- Q+ indicates an engagement which was analyzed as part of the QJM low-intensity combat study in 1988 (14 total).

- T indicates an engagement analyzed with the TNDM (20 total).

Are they any similar for naval engagements? On some levels, they would seem to be more straightforward.

Russell,

Not sure I understand the question. We did put together a list of Naval Engagements for use in model development and model testing. It is on page 13 here:

http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/pdf/v2n2.pdf

Thanks, That is exactly what I was wondering. The article preceding the list highlights some of the issues well.

I have some modern naval simulations, but they tend toward balanced scenarios. Real life isn’t always so balanced.

Yea, I am not sure there have been any balanced naval fights since 1942.

Casualty figures for the PTO seem to be either missing or are often rather vague.