My previous posts have discussed the Japanese Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) and the aircraft used to perform the Defensive Counter Air (DCA) mission. To accomplish this, the JASDF is supported by an extensive air defense system which closely mirrors U.S. Air Force (USAF) and U.S. Navy (USN) systems and has co-evolved as technology and threats have changed over time.

Japan’s integrated air defense network and the current challenges it faces are both rooted in the Cold War origins of the modern U.S. air defense network.

On June 25, 1950, North Korea launched an invasion of South Korea, drawing the United States into a war that would last for three years. Believing that the North Korean attack could represent the first phase of a Soviet-inspired general war, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered Air Force air defense forces to a special alert status. In the process of placing forces on heightened alert, the Air Force uncovered major weaknesses in the coordination of defensive units to defend the nation’s airspace. As a result, an air defense command and control structure began to develop and Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZ) were staked out along the nation’s frontiers. With the establishment of ADIZ, unidentified aircraft approaching North American airspace would be interrogated by radio. If the radio interrogation failed to identify the aircraft, the Air Force launched interceptor aircraft to identify the intruder visually. In addition, the Air Force received Army cooperation. The commander of the Army’s Antiaircraft Artillery Command allowed the Air Force to take operational control of the gun batteries as part of a coordinated defense in the event of attack.

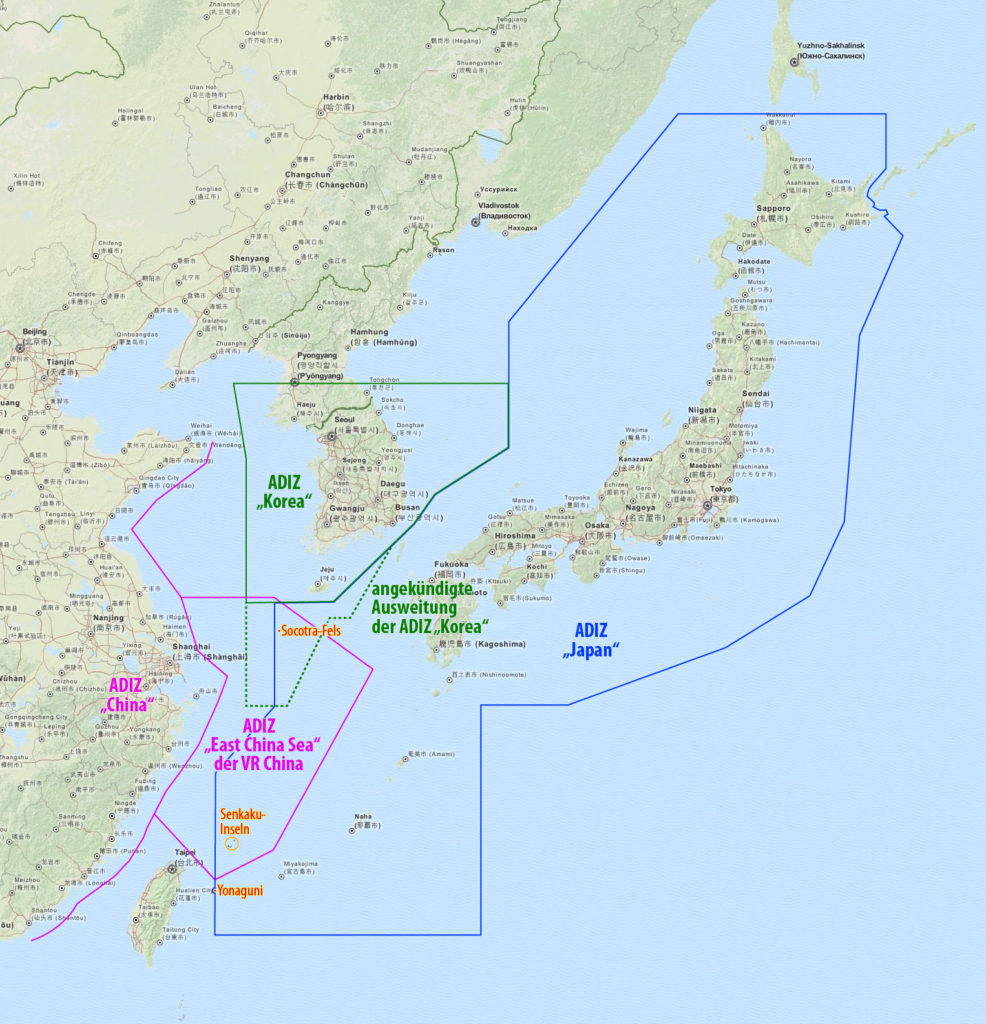

In addition to North America, the U.S. unilaterally declared ADIZs to protect Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Taiwan in 1950. This action had no explicit foundation in international law.

Under the Convention on International Civil Aviation (the Chicago Convention), each State has complete and exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above its territory. While national sovereignty cannot be delegated, the responsibility for the provision of air traffic services can be delegated.… [A] State which delegates to another State the responsibility for providing air traffic services within airspace over its territory does so without derogation of its sovereignty.

This precedent set the stage for China to unilaterally declare ADIZs its own in 2013 that overlap those of Japan in the East China Sea. China’s ADIZs have the same international legal validity as those of the U.S. and Japan, which has muted criticism of China’s actions by those countries.

Recent activity by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and nuclear and missile testing by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea) is prompting incremental upgrades and improvements to the Japanese air defense radar network.

In August 2018, six Chinese H-6 bombers passed between Okinawa’s main island and Miyako Island heading north to Kii Peninsula. “The activities by Chinese aircraft in surrounding areas of our country have become more active and expanding its area of operation,” the spokesman [of the Japanese Ministry of Defense] said.… “There were no units placed on the islands on the Pacific Ocean side, such as Ogasawara islands, which conducted monitoring of the area…and the area was without an air defense capability.”

Such actions by the PLAAF and People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) have provided significant rationale in the Japanese decision to purchase the F-35B and retrofit their Izumo-class helicopter carriers to operate them, as the Pacific Ocean side of Japan is relatively less developed for air defense and airfields for land-based aircraft.

My next post will look at the development of the U.S. air defense network and its eventual integration with those of Japan and NATO