This is the first in a series of Orders of Battle (OOB) posts, which will cover Japan, the neighboring and regional powers in East Asia, as well as the major global players, with a specific viewpoint on their military forces in East Asia and the Greater Indo-Pacific. The idea is to provide a catalog of forces and capabilities, but also to provide some analysis of how those forces are linked to the nation’s strategy.

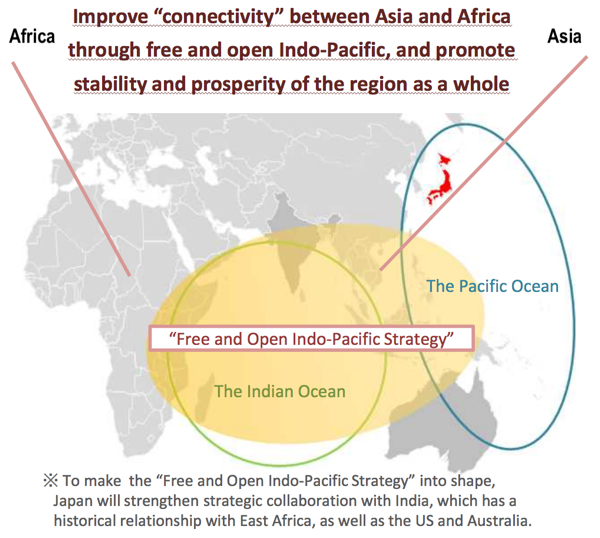

The geographic term “Indo-Pacific” is a relatively new one, and referred to by name in the grand strategy as detailed by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) in April 2017. It also aligns with the strategy and terminology used by US Defense Secretary James Mattis at the Shangri-La conference in June 2018. Dr. Michael J. Green has a good primer on the evolution of Japan’s grand strategy, along with a workable definition of the term:

What is “grand strategy”? It is the integration of all instruments of national power to shape a more favorable external environment for peace and prosperity. These comprehensive instruments of power are diplomatic, informational, military and economic. Successful grand strategies are most important in peacetime, since war may be considered the failure of strategy.

Nonetheless, the seminal speech by Vice President Pence regarding China policy on 4 October 2018, had an articulation of Chinese grand strategy: “Beijing is employing a whole-of-government approach, using political, economic, and military tools, as well as propaganda, to advance its influence and benefit its interests in the United States.” The concept of grand strategy is not new; Thucydides is often credited with the first discussion of this concept in History of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). It is fundamentally about the projection of power in all its forms.

With the Focus on the Indo-Pacific Strategy, What About the Home Islands?

The East Asian region has some long simmering conflicts, legacies from past wars, such as World War II (or Great Pacific War) (1937-1945), the Korean War (1950-1953), and the Chinese Civil War (1921-1947). These conflicts led to static and stable borders, across which a “military balance” is often referred to, and publications from think tanks often refer to this, for example the Institute for International and Strategic Studies (IISS) offers a publication with this title. The points emphasized by IISS in the 2018 edition are “new arms orders and deliveries graphics and essays on Chinese and Russian air-launched weapons, artificial intelligence and defence, and Russian strategic-force modernisation.”

So, the Japanese military has two challenges, maintain the balance of power at home, that is playing defense, with neighbors who are changing and deploying new capabilities that have a material effect on this balance. And, as seen above Japan is working to build an offense as part of the new grand strategy, and military forces play a role.

Given the size and capability of the Japanese military forces, it is possible to project power at great distances from the Japanese home waters. Yet, as a legacy from the Great Pacific War, the Japanese do not technically have armed forces. The constitution, imposed by Americans, officially renounces war as a sovereign right of the nation.

In July 2014, the constitution was officially ”re-interpreted” to allow collective self-defense. The meaning was that if the American military was under attack, for example in Guam, nearby Japanese military units could not legally engage with the forces attacking the Americans, even though they are allied nations, and conduct numerous training exercises together, that is, they train to fight together. This caused significant policy debate in Japan.

More recently, as was an item of debate in the national election in September 2018, the legal status of the SDF is viewed as requiring clarification, with some saying they are altogether illegal. “It’s time to tackle a constitutional revision,” Abe said in a victory speech.

The original defense plan was for the American military to defend Japan. The practical realities of the Cold War and the Soviet threat to Japan ended up creating what are technically “self-defense forces” (SDF) in three branches:

- Japan Ground Self-Defense Forces (JGSDF)

- Japan Maritime Self-Defense Forces (JGSDF)

- Japan Air Self-Defense Forces (JASDF)

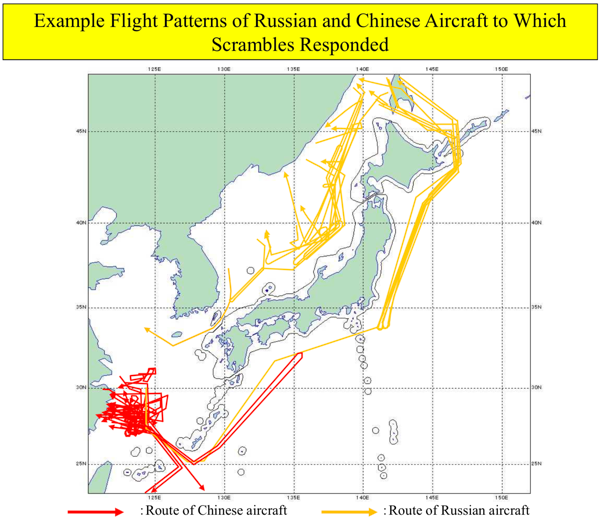

In the next post, these forces will be cataloged, with specific capabilities linked to Japanese strategy. As a quick preview, the map below illustrates the early warning radar sites, airborne early warning aircraft, and fighter-interceptor aircraft, charged with the mission to maintain a balance of power in the air, as Russian and Chinese air forces challenge the sovereignty of Japanese airspace. With the Russians, this is an old dance from the Cold War, but recently the Chinese have gotten into this game as well.