“If we maintain our faith in God, love of freedom, and superior global airpower, the future [of the US] looks good.” — U.S. Air Force General Curtis E. LeMay (Commander, U.S. Strategic Command, 1948-1957)

“If we maintain our faith in God, love of freedom, and superior global airpower, the future [of the US] looks good.” — U.S. Air Force General Curtis E. LeMay (Commander, U.S. Strategic Command, 1948-1957)

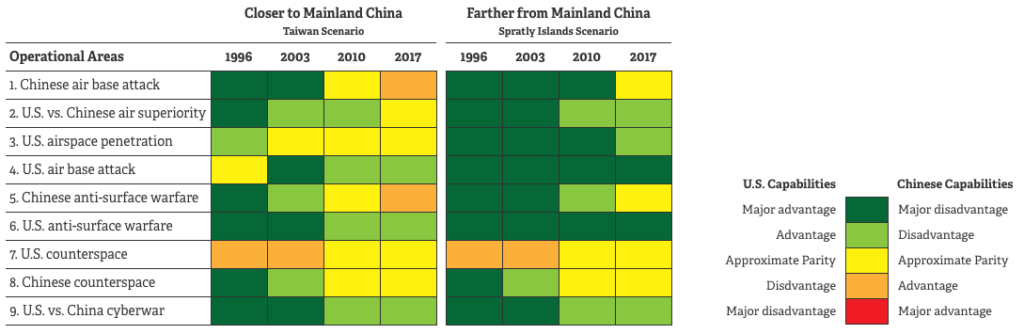

Curtis LeMay was involved in the formation of RAND Corporation after World War II. RAND created several models to measure the dynamics of the US-China military balance over time. Since 1996, this has been computed for two scenarios, differing by range from mainland China: one over Taiwan and the other over the Spratly Islands. The results of the model results for selected years can be seen in the graphic below.

The capabilities listed in the RAND study are interesting, notable in that the air superiority category, rough parity exists as of 2017. Also, the ability to attack air bases has given an advantage to the Chinese forces.

The capabilities listed in the RAND study are interesting, notable in that the air superiority category, rough parity exists as of 2017. Also, the ability to attack air bases has given an advantage to the Chinese forces.

Investigating the methodology used does not yield any precise quantitative modeling examples, as would be expected in a rigorous academic effort, although there is some mention of statistics, simulation and historical examples.

The analysis presented here necessarily simplifies a great number of conflict characteristics. The emphasis throughout is on developing and assessing metrics in each area that provide a sense of the level of difficulty faced by each side in achieving its objectives. Apart from practical limitations, selectivity is driven largely by the desire to make the work transparent and replicable. Moreover, given the complexities and uncertainties in modern warfare, one could make the case that it is better to capture a handful of important dynamics than to present the illusion of comprehensiveness and precision. All that said, the analysis is grounded in recognized conclusions from a variety of historical sources on modern warfare, from the air war over Korea and Vietnam to the naval conflict in the Falklands and SAM hunting in Kosovo and Iraq. [Emphasis added].

We coded most of the scorecards (nine out of ten) using a five-color stoplight scheme to denote major or minor U.S. advantage, a competitive situation, or major or minor Chinese advantage. Advantage, in this case, means that one side is able to achieve its primary objectives in an operationally relevant time frame while the other side would have trouble in doing so. [Footnote] For example, even if the U.S. military could clear the skies of Chinese escort fighters with minimal friendly losses, the air superiority scorecard could be coded as “Chinese advantage” if the United States cannot prevail while the invasion hangs in the balance. If U.S. forces cannot move on to focus on destroying attacking strike and bomber aircraft, they cannot contribute to the larger mission of protecting Taiwan.

All of the dynamic modeling methodology (which involved a mix of statistical analysis, Monte Carlo simulation, and modified Lanchester equations) is publicly available and widely used by specialists at U.S. and foreign civilian and military universities.” [Emphasis added].

As TDI has contended before, the problem with using Lanchester’s equations is that, despite numerous efforts, no one has been able to demonstrate that they accurately represent real-world combat. So, even with statistics and simulation, how good are the results if they have relied on factors or force ratios with no relation to actual combat?

What about new capabilities?

As previously posted, the Kratos Mako Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV), marketed as the “unmanned wingman,” has recently been cleared for export by the U.S. State Department. This vehicle is specifically oriented towards air-to-air combat, is stated to have unparalleled maneuverability, as it need not abide by limits imposed by human physiology. The Mako “offers fighter-like performance and is designed to function as a wingman to manned aircraft, as a force multiplier in contested airspace, or to be deployed independently or in groups of UASs. It is capable of carrying both weapons and sensor systems.” In addition, the Mako has the capability to be launched independently of a runway, as illustrated below. The price for these vehicles is three million each, dropping to two million each for an order of at least 100 units. Assuming a cost of $95 million for an F-35A, we can imagine a hypothetical combat scenario pitting two F-35As up against 100 of these Mako UCAVs in a drone swarm; a great example of the famous phrase, quantity has a quality all its own.

How to evaluate the effects of these possible UCAV drone swarms?

In building up towards the analysis of all of these capabilities in the full theater, campaign level conflict, some supplemental wargaming may be useful. One game that takes a good shot at modeling these dynamics is Asian Fleet. This is a part of the venerable Fleet Series, published by Victory Games, designed by Joseph Balkoski to model modern (that is Cold War) naval combat. This game system has been extended in recent years, originally by Command Magazine Japan, and then later by Technical Term Gaming Company.

More to follow on how this game transpires!