The same friend of TDI who asked about ‘Evett’s Rates,” the British casualty estimation methodology during World War II, also mentioned that the work of Albert G. Love III was now available on-line. Rick Atkinson also referenced “Love’s Tables” in The Guns At Last Light.

The same friend of TDI who asked about ‘Evett’s Rates,” the British casualty estimation methodology during World War II, also mentioned that the work of Albert G. Love III was now available on-line. Rick Atkinson also referenced “Love’s Tables” in The Guns At Last Light.

In 1931, Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier General) Love, then a Medical Corps physician in the U.S. Army Medical Field Services School, published a study of American casualty data in the recent Great War, titled “War Casualties.”[1] This study was likely the source for tables used for casualty estimation by the U.S. Army through 1944.[2]

Love, who had no advanced math or statistical training, undertook his study with the support of the Army Surgeon General, Merritte W. Ireland, and initial assistance from Dr. Lowell J. Reed, a professor of biostatistics at John Hopkins University. Love’s posting in the Surgeon General’s Office afforded him access to an array of casualty data collected from the records of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, as well as data from annual Surgeon General reports dating back to 1819, the official medical history of the U.S. Civil War, and U.S. general population statistics.

Love’s research was likely the basis for rate tables for calculating casualties that first appeared in the 1932 edition of the War Department’s Staff Officer’s Field Manual.[3]

The 1932 Staff Officer’s Field Manual estimation methodology reflected Love’s sophisticated understanding of the factors influencing combat casualty rates. It showed that both the resistance and combat strength (and all of the factors that comprised it) of the enemy, as well as the equipment and state of training and discipline of the friendly troops had to be taken into consideration. The text accompanying the tables pointed out that loss rates in small units could be quite high and variable over time, and that larger formations took fewer casualties as a fraction of overall strength, and that their rates tended to become more constant over time. Casualties were not distributed evenly, but concentrated most heavily among the combat arms, and in the front-line infantry in particular. Attackers usually suffered higher loss rates than defenders. Other factors to be accounted for included the character of the terrain, the relative amount of artillery on each side, and the employment of gas.

The 1941 iteration of the Staff Officer’s Field Manual, now designated Field Manual (FM) 101-10[4], provided two methods for estimating battle casualties. It included the original 1932 Battle Casualties table, but the associated text no longer included the section outlining factors to be considered in calculating loss rates. This passage was moved to a note appended to a new table showing the distribution of casualties among the combat arms.

Rather confusingly, FM 101-10 (1941) presented a second table, Estimated Daily Losses in Campaign of Personnel, Dead and Evacuated, Per 1,000 of Actual Strength. It included rates for front line regiments and divisions, corps and army units, reserves, and attached cavalry. The rates were broken down by posture and tactical mission.

The source for this table is unknown, nor the method by which it was derived. No explanatory text accompanied it, but a footnote stated that “this table is intended primarily for use in school work and in field exercises.” The rates in it were weighted toward the upper range of the figures provided in the 1932 Battle Casualties table.

The October 1943 edition of FM 101-10 contained no significant changes from the 1941 version, except for the caveat that the 1932 Battle Casualties table “may or may not prove correct when applied to the present conflict.”

The October 1944 version of FM 101-10 incorporated data obtained from World War II experience.[5] While it also noted that the 1932 Battle Casualties table might not be applicable, the experiences of the U.S. II Corps in North Africa and one division in Italy were found to be in agreement with the table’s division and corps loss rates.

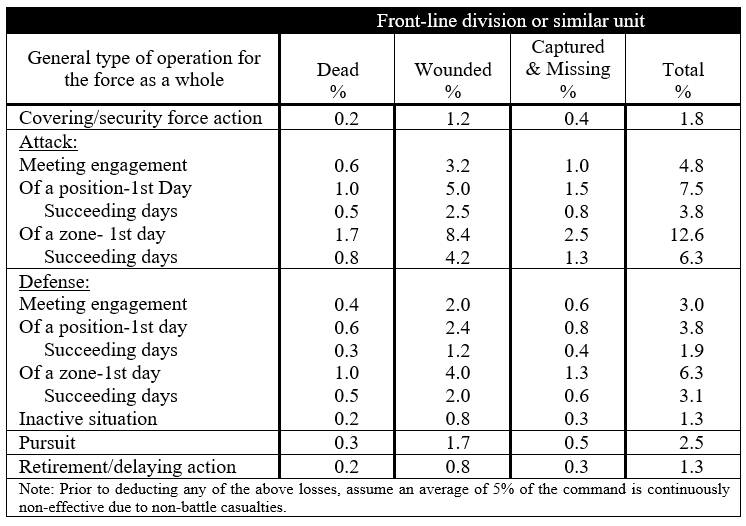

FM 101-10 (1944) included another new table, Estimate of Battle Losses for a Front-Line Division (in % of Actual Strength), meaning that it now provided three distinct methods for estimating battle casualties.

Like the 1941 Estimated Daily Losses in Campaign table, the sources for this new table were not provided, and the text contained no guidance as to how or when it should be used. The rates it contained fell roughly within the span for daily rates for severe (6-8%) to maximum (12%) combat listed in the 1932 Battle Casualty table, but would produce vastly higher overall rates if applied consistently, much higher than the 1932 table’s 1% daily average.

FM 101-10 (1944) included a table showing the distribution of losses by branch for the theater based on experience to that date, except for combat in the Philippine Islands. The new chart was used in conjunction with the 1944 Estimate of Battle Losses for a Front-Line Division table to determine daily casualty distribution.

The final World War II version of FM 101-10 issued in August 1945[6] contained no new casualty rate tables, nor any revisions to the existing figures. It did finally effectively invalidate the 1932 Battle Casualties table by noting that “the following table has been developed from American experience in active operations and, of course, may not be applicable to a particular situation.” (original emphasis)

NOTES

[1] Albert G. Love, War Casualties, The Army Medical Bulletin, No. 24, (Carlisle Barracks, PA: 1931)

[2] This post is adapted from TDI, Casualty Estimation Methodologies Study, Interim Report (May 2005) (Altarum) (pp. 314-317).

[3] U.S. War Department, Staff Officer’s Field Manual, Part Two: Technical and Logistical Data (Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1932)

[4] U.S. War Department, FM 101-10, Staff Officer’s Field Manual: Organization, Technical and Logistical Data (Washington, D.C., June 15, 1941)

[5] U.S. War Department, FM 101-10, Staff Officer’s Field Manual: Organization, Technical and Logistical Data (Washington, D.C., October 12, 1944)

[6] U.S. War Department, FM 101-10 Staff Officer’s Field Manual: Organization, Technical and Logistical Data (Washington, D.C., August 1, 1945)