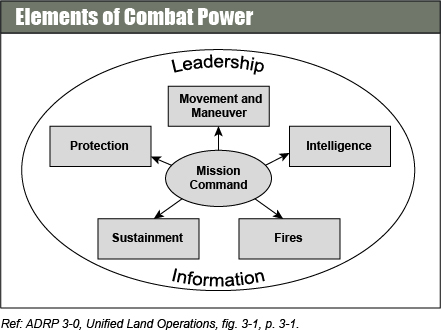

One of the fundamental concepts of U.S. warfighting doctrine is combat power. The current U.S. Army definition is “the total means of destructive, constructive, and information capabilities that a military unit or formation can apply at a given time. (ADRP 3-0).” It is the construct commanders and staffs are taught to use to assess the relative effectiveness of combat forces and is woven deeply throughout all aspects of U.S. operational thinking.

To execute operations, commanders conceptualize capabilities in terms of combat power. Combat power has eight elements: leadership, information, mission command, movement and maneuver, intelligence, fires, sustainment, and protection. The Army collectively describes the last six elements as the warfighting functions. Commanders apply combat power through the warfighting functions using leadership and information. [ADP 3-0, Operations]

Yet, there is no formal method in U.S. doctrine for estimating combat power. The existing process is intentionally subjective and largely left up to judgment. This is problematic, given that assessing the relative combat power of friendly and opposing forces on the battlefield is the first step in Course of Action (COA) development, which is at the heart of the U.S. Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP). Estimates of combat power also figure heavily in determining the outcomes of wargames evaluating proposed COAs.

The Existing Process

The Army’s current approach to combat power estimation is outlined in Field Manual (FM) 6-0 Commander and Staff Organization and Operations (2014). Planners are instructed to “make a rough estimate of force ratios of maneuver units two levels below their echelon.” They are then directed to “compare friendly strengths against enemy weaknesses, and vice versa, for each element of combat power.” It is “by analyzing force ratios and determining and comparing each force’s strengths and weaknesses as a function of combat power” that planners gain insight into tactical and operational capabilities, perspectives, vulnerabilities, and required resources.

That is it. Planners are told that “although the process uses some numerical relationships, the estimate is largely subjective. Assessing combat power requires assessing both tangible and intangible factors, such as morale and levels of training.” There is no guidance as to how to determine force ratios [numbers of troops or weapons systems?]. Nor is there any description of how to relate force calculations to combat power. Should force strengths be used somehow to determine a combat power value? Who knows? No additional doctrinal or planning references are provided.

Planners then use these subjective combat power assessments as they shape potential COAs and test them through wargaming. Although explicitly warned not to “develop and recommend COAs based solely on mathematical analysis of force ratios,” they are invited at this stage to consult a table of “minimum historical planning ratios as a starting point.” The table is clearly derived from the ubiquitous 3-1 rule of combat. Contrary to what FM 6-0 claims, neither the 3-1 rule nor the table have a clear historical provenance or any sort of empirical substantiation. There is no proven validity to any of the values cited. It is not even clear whether the “historical planning ratios” apply to manpower, firepower, or combat power.

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.

During this phase, planners are advised to account for “factors that are difficult to gauge, such as impact of past engagements, quality of leaders, morale, maintenance of equipment, and time in position. Levels of electronic warfare support, fire support, close air support, civilian support, and many other factors also affect arraying forces.” FM 6-0 offers no detail as to how these factors should be measured or applied, however.

FM 6-0 also addresses combat power assessment for stability and civil support operations through troop-to-task analysis. Force requirements are to be based on an estimate of troop density, a “ratio of security forces (including host-nation military and police forces as well as foreign counterinsurgents) to inhabitants.” The manual advises that most “most density recommendations fall within a range of 20 to 25 counterinsurgents for every 1,000 residents in an area of operations. A ratio of twenty counterinsurgents per 1,000 residents is often considered the minimum troop density required for effective counterinsurgency operations.”

While FM 6-0 acknowledges that “as with any fixed ratio, such calculations strongly depend on the situation,” it does not mention that any references to force level requirements, tie-down ratios, or troop density were stripped from both Joint and Army counterinsurgency manuals in 2013 and 2014. Yet, this construct lingers on in official staff planning doctrine. (Recent research challenged the validity of the troop density construct but the Defense Department has yet to fund any follow-on work on the subject.)

The Army Has Known About The Problem For A Long Time

The Army has tried several solutions to the problem of combat power estimation over the years. In the early 1970s, the U.S. Army Center for Army Analysis (CAA; known then as the U.S. Army Concepts & Analysis Agency) developed the Weighted Equipment Indices/Weighted Unit Value (WEI/WUV or “wee‑wuv”) methodology for calculating the relative firepower of different combat units. While WEI/WUV’s were soon adopted throughout the Defense Department, the subjective nature of the method gradually led it to be abandoned for official use.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College (CGSC) published the ST 100-9 and ST 100-3 student workbooks that contained tables of planning factors that became the informal basis for calculating combat power in staff practice. The STs were revised regularly and then adapted into spreadsheet format in the late 1990s. The 1999 iteration employed WEI/WEVs as the basis for calculating firepower scores used to estimate force ratios. CGSC stopped updating the STs in the early 2000s, as the Army focused on irregular warfare.

With the recently renewed focus on conventional conflict, Army staff planners are starting to realize that their planning factors are out of date. In an attempt to fill this gap, CGSC developed a new spreadsheet tool in 2012 called the Correlation of Forces (COF) calculator. It apparently drew upon analysis done by the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command Analysis Center (TRAC) in 2004 to establish new combat unit firepower scores. (TRAC’s methodology is not clear, but if it is based on this 2007 ISMOR presentation, the scores are derived from runs by an unspecified combat model modified by factors derived from the Army’s unit readiness methodology. If described accurately, this would not be an improvement over WEI/WUVs.)

The COF calculator continues to use the 3-1 force ratio tables. It also incorporates a table for estimating combat losses based on force ratios (this despite ample empirical historical analysis showing that there is no correlation between force ratios and casualty rates).

While the COF calculator is not yet an official doctrinal product, CGSC plans to add Marine Corps forces to it for use as a joint planning tool and to incorporate it into the Army’s Command Post of the Future (CPOF). TRAC is developing a stand-alone version for use by force developers.

The incorporation of unsubstantiated and unvalidated concepts into Army doctrine has been a long standing problem. In 1976, Huba Wass de Czege, then an Army major, took both “loosely structured and unscientific analysis” based on intuition and experience and simple counts of gross numbers to task as insufficient “for a clear and rigorous understanding of combat power in a modern context.” He proposed replacing it with a analytical framework for analyzing combat power that accounted for both measurable and intangible factors. Adopting a scrupulous method and language would overcome the simplistic tactical analysis then being taught. While some of the essence of Wass de Czege’s approach has found its way into doctrinal thinking, his criticism of the lack of objective and thorough analysis continues to echo (here, here, and here, for example).

Despite dissatisfaction with the existing methods, little has changed. The problem with this should be self-evident, but I will give the U.S. Naval War College the final word here:

Fundamentally, all of our approaches to force-on-force analysis are underpinned by theories of combat that include both how combat works and what matters most in determining the outcomes of engagements, battles, campaigns, and wars. The various analytical methods we use can shed light on the performance of the force alternatives only to the extent our theories of combat are valid. If our theories are flawed, our analytical results are likely to be equally wrong.

Interesting. IMHO war-gaming is the only way to test relative combat power. The tactics used often neutralise a significant part of the combat force of one side. For example in the “Run South” in the battle of Jutland, Beatty has a much greater force but throws it away with poor tactics, misdirecting the 5th Battle Group so they are not involved in the battle to name but one mistake.

Force ratios have their place but only represent an ideal potential not a realised battle effectiveness.

What about Maj. Allen Raymond’s Monograph, “Assessing Combat Power: A Methodology for Tactical Battle Staffs”? If I recall correctly it included a list with the combat rating of individual NATO and Warsaw Pact weapon systems, while the methodology involved an assessement and summation of battalion, brigade and divisional fighting power.

There are about a dozen PME theses and monographs that directly address the question of combat power, and many others that deal with topics that include combat power. Raymond’s thesis appears to develop a variant of the WEI/WUV firepower scoring methodology. The problem as I see it is that firepower, however calculated, is at best an incomplete measure of combat power.

I concur that wargaming is a pretty indispensable part of military planning. There are two problems that I see with the Army’s approach, however. First, it has no method for calculating combat power. Firepower scores and force ratio estimates are an inadequate substitute. Second, without a clear measure of combat power, the outcomes of the wargames are basically determined by subjective judgement. That judgement may or may not be correct, but the ensuing military decision-making is dependent on it. This is what Wass de Czege was trying to get at with his criticism of the Army’s reliance on intuition and experience instead of clear and rigorous analysis.

I do not see why war-gaming outcomes need to be subjective. If the war-game is set up with tangible objectives and victory conditions (e.g. geographic area to be occupied and limits on the attackers acceptable loses as well as a time frame within which the objectives have to be achieved) then it should be apparent at the end of the time frame whether the attacker has won or lost. The position of the attackers and defender’s units on the table should leave the outcome beyond any reasonable doubt.

A wargame needs some method of adjudicating the results of combat in the battles being played. How else does one tell if an attacker wins or loses? My point is that neither force ratios nor subjective assessments of combat power are objective methods of determining combat outcomes. They are subjective guesses, which may or may not be accurate. That means the outcomes of wargames using subjective methods of adjudication are going to be subjective.

For example, the Japanese Navy wargamed their plan for the Midway operation in 1942. After U.S. forces in the game sank several Japanese aircraft carriers, referees determined that to be an invalid outcome and magically resurrected the Japanese ships, which went on to win the battle. Reality turned out to be different. Subjective methods produce subjective results.

But do the adjudication methods have to be subjective. For example, if we are using criteria such as geographic area to be occupied, limits on the attackers acceptable loses as well as a time frame within which the objectives have to be achieved would these not be objective?

What do you think are objective criteria for war-game victory?

I suspect we are talking about different things here, so let me clarify.

The staff of Brigade X is wargaming potential COAs for attacking an Red battalion defending a town. The first COA is a direct assault on the defending Red battalion with two Blue battalions. How does one determine the outcome of that planned assault? The Army’s approach is for the planners to determine the force ratios of the Red and Blue forces based on available intelligence information. The planners are then to make an assessment of the combat power of each side. They are then to consult the “historical minimum planning ratio” table and decide if the proper amount of force has been allocated. They are also supposed to account how “factors difficult to gauge” might affect the results. From this, for the purpose of facilitating the wargame of that COA, the planners are somehow supposed to determine whether or not the assault succeeds or not. What criteria are they supposed to use? Well, if they stick with the 3-1 rule, they will probably conclude that it will fail (which they probably will do, because time is short in battlefield planning and the brigade staff won’t have the luxury of extended research and debate).

That is what I mean when I refer to subjective adjudication based on guesswork. They might determine that the assault will fail, so the COA is a bad one. Or they might determine that the assault might succeed, which means the COA is a viable alternative. Either way, the planners will not be able to provide any sort of objective substantiation for why they think a particular outcome is valid, at least based on official doctrinal guidance.

My larger point is that if the planners cannot reliably determine who might win or lose individual battles within a wargame, then it doesn’t really matter what the overall COA wargame criteria might be.

In the staff wargaming sessions I took part in, there was no use of WEI/WEU methodology or any other model as we determined what courses of action we would recommend.

I would use a relatively simple method of combat adjudication to try to determine a more coherent outcome of an engagement. It is pretty well-known as “Battle Calculous) but it is just multiplication and division.

Its step’s were to evaluate the amount of time you had to engage the enemy. I do not claim this method as an invention, but I do forget who told me about it the first time.

In the best case, some vehicles are sent out to drive several routes through the engagement areas and observers time the amount of time they are visible. By some means (guessing) this is extrapolated to the rest of the unit sector.

Next you to determine the number of targets in the array and how much of them you can shoot at. For this I had a notional Motorized Rifle Regiment templates on a piece of acetate and attempted to determine the percent of the array would be visible.

We then took our forces and determined how much we could fire at the target by weapon system (e.g. an M60A1/3 could should 6 – 8 targets per minute). We then estimated the probability of hit (As a company commander, I used the hit rate from tank gunnery qualification using training ammunition which we knew to be less accurate than service ammunition), I used a probably too generous 0.9 and a much too generous 0.8 pk. Let’s say that we had 5 minutes of visibility of the array.

So, I would multiply 14 * 6 *.9*.8 * 5 = a maximum of 302 good shots. A reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion had about 100 targets, so from this I would deduce I could probably kill the battalion in the time allotted. My company would have had 14* 56 = 784 tank killing rounds available.

I would then subtract the number of my vehicles that would be killed (lets say 5 if we were fighting a BTR battalion or 7 if it was BMPs, because we were defending) and subtract those shots to see if I had enough power after losses to deal with the enemy.

If it turned out I didn’t have enough, then I would have several options (but I always planned to fight alone):

-Change my plan and reposition the force to decrease potential losses.

put some obstacles in to extend my engagement time.

-ask for some more attachments (say an Infantry Platoon or Anti-tank platoon or section from our sister battalion).

-priority of artillery fire

-priority of air support (Attack helicopters or CAS).

After I got a semi-good handle on this at the company level, I could extrapolate it at the battalion or brigade level.

Sometimes it even worked when using MILES.

Naturally my model suffered from my biases and any automated model I would develop would also suffer them, but in an automated model, at least the bias would be ‘standardized’ and could potentially be updated by others based on their own experience.

Now, how it usually worked in my experience is we looked at the rough force ratio (tanks to tanks, BMPs to BFV, etc), see if it met the 3:1 ratio, and then guessed. Sometimes the person doing the game would brief his estimate of the losses at each stage (determined by some unknown method (me included because you didn’t always have time to do all the math for the method above)..

Every course of action was always judged as doable, because if it is not doable, then you don’t recommend it.

(As a note, as a Brigade S-4, I would come up with potential losses and brief those during my part of the game or privately to my brigade commander afterwards.)

We never thought we were making a prediction, nor did I ever think to make notes of our predictions and compare them to the results from the After Action Review. Sadly, this thought never passed my mind until I had been out of the Army for way too long.

This method is somewhat subjective (PH/PK), friendly losses, but has some objective measures (time the target is visibile, percent of the target you can engage, some metrics for hit, range, etc.), but if it were placed in a standardized tool, at least at the company – brigade level it would consistent and allow for updates. Division or higher units might need a more aggregated method.

Your value and experience may vary.

OK. So what is the objective alternative?

That is an excellent question! I will seek to address it in some detail in forthcoming posts. In the meantime, I heartily recommend searching up Huba Wass de Czege’s 1976 CGSC monograph “Understanding and Developing Combat Power.” It will probably ring some familiar notes for folks familiar with Trevor Dupuy’s work.

Thank you. I am really looking forward to those posts as I do a lot of historical war-gaming and this may enable me to enhance the approach used. I will read up the references you mention.

I also recommend Vincent Tedesco’s SAMS monograph “Tactical Alchemy-Heavy Division Tactical Maneuver Planning Guides and the Army’s Neglect of the Science of War” (2000) http://tedescos.com/files/Tactical_Alchemy.pdf

I’m glad you found my monograph of some use.

I may have missed something but I have not yet seen these posts. Did I miss the posts or are they still in the pipeline and when would they be available?

[…] to seven subordinate battalions. The three infantry battalions form the core of the brigade’s combat power. This structure is the result of decisions made when the Army was downsized from four brigade […]

[…] to seven subordinate battalions. The three infantry battalions form the core of the brigade’s combat power. This structure is the result of decisions made when the Army was downsized from four brigade […]

[…] to seven subordinate battalions. The three infantry battalions form the core of the brigade’s combat power. This structure is the result of decisions made when the Army was downsized from four brigade […]

[…] to seven subordinate battalions. The three infantry battalions form the core of the brigade’s combat power. This structure is the result of decisions made when the Army was downsized from four brigade […]

[…] battalions. The three infantry battalions form the core of the brigade’s combat power. This structure is the result of decisions made when the Army was downsized from four brigade […]