For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in an article in Joint Forces Quarterly. In order to move beyond the abstract, Hurst looked at how drone swarms “should be inserted into the tactical concepts of today—chiefly, the five forms of offensive maneuver recognized under Army doctrine.”

For a while now, military pundits have speculated about the role robotic drones and swarm tactics will play in future warfare. U.S. Army Captain Jules Hurst recently took a first crack at adapting drones and swarms into existing doctrine in an article in Joint Forces Quarterly. In order to move beyond the abstract, Hurst looked at how drone swarms “should be inserted into the tactical concepts of today—chiefly, the five forms of offensive maneuver recognized under Army doctrine.”

Hurst pointed out that while drone design currently remains in flux, “for assessment purposes, future swarm combatants will likely be severable into two broad categories: fire support swarms and maneuver swarms.”

In Hurst’s reckoning, the chief advantage of fire support swarms would be their capacity for overwhelming current air defense systems to deliver either human-targeted or semi-autonomous precision fires. Their long-range endurance of airborne drones also confers an ability to take and hold terrain that current manned systems do not possess.

The primary benefits of ground maneuver swarms, according to Hurst, would be their immunity from the human element of fear, giving them a resilient, persistent level of combat effectiveness. Their ability to collect real-time battlefield intelligence makes them ideal for enabling modern maneuver warfare concepts.

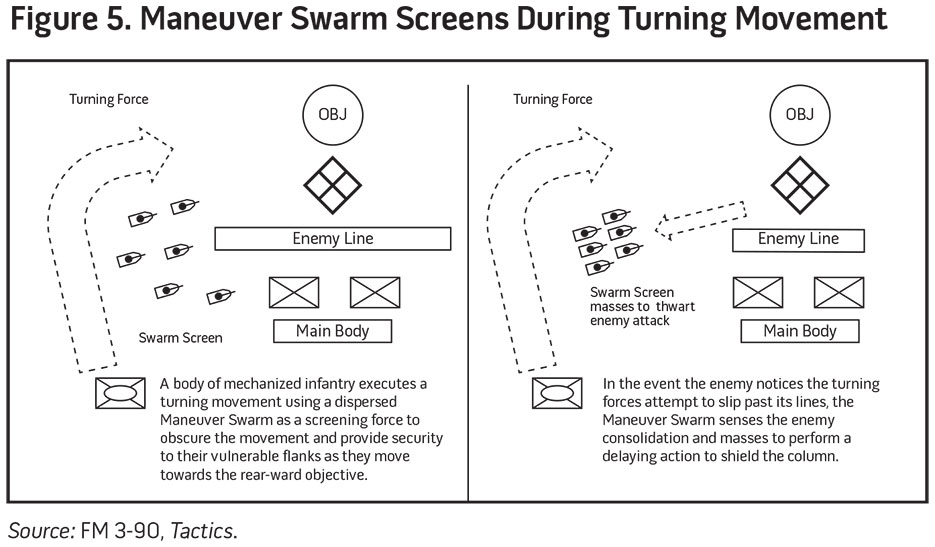

Hurst examines how these capabilities could be exploited through each of the Army’s current schemes of maneuver: infiltration, penetration, frontal attack, envelopment, and the turning maneuver. While concluding that “ultimately, the technological limitations and advantages of maneuver swarms and fire support swarms will determine their uses,” Hurst acknowledged the critical role Army institutional leadership must play in order to successfully utilize the new technology on the battlefield.

U.S. officers and noncommissioned officers can accelerate that comfort [with new weapons] by beginning to postulate about the use of swarms well before they hit the battlefield. In the vein of aviation visionaries Billy Mitchell and Giulio Douhet, members of the Department of Defense must look forward 10, 20, or even 30 years to when artificial intelligence allows the deployment of swarm combatants on a regular basis. It will take years of field maneuvers to perfect the employment of swarms in combat, and the concepts formed during these exercises may be shattered during the first few hours of war. Even so, the U.S. warfighting community must adopt a venture capital mindset and accept many failures for the few novel ideas that may produce game-changing results.

Trevor Dupuy would have agreed. He argued that the crucial factor in military innovation was not technology, but the organization approach to using it. Based on his assessment of historical patterns, Dupuy derived a set of preconditions necessary for the successful assimilation of new technology into warfare.

- An imaginative, knowledgeable leadership focused on military affairs, supported by extensive knowledge of, and competence in, the nature and background of the existing military system.

- Effective coordination of the nation’s economic, technological-scientific, and military resources.

- There must exist industrial or developmental research institutions, basic research institutions, military staffs and their supporting institutions, together with administrative arrangements for linking these with one another and with top decision-making echelons of government.

- These bodies must conduct their research, developmental, and testing activities according to mutually familiar methods so that their personnel can communicate, can be mutually supporting, and can evaluate each other’s results.

- The efforts of these institutions—in related matters—must be directed toward a common goal.

- Opportunity for battlefield experimentation as a basis for evaluation and analysis.

Is the U.S. Army up to the task?

I wonder if Captain Jules Hurst knows he is referencing a publication which no longer exists? Superseded by FM 3-90.1 in March 2013.

Dupey’s logic makes sense when you need an industrial base to advance a technology. But there is (IMO) a counter example. The use of naval mines (then called torpedoes) had an outsized effect on naval operations at the point when they were devices out of the tinkerers lab. The technology could be introduced at a relatively low cost by only a few individuals.

If you come forward to today, the potential for various home brewed weaponry weather it be electronic, cyber, biological, or something else seems to be very much where we are headed to.