Trevor Dupuy considered intensity to be another combat phenomena influenced by human factors. The variation in the intensity of combat is an aspect of battle that is widely acknowledged but little studied.

No one who has paid any attention at all to historical combat statistics can have failed to notice that some battles have been very bloody and hard-fought, while others—often under circumstances superficially similar—have reached a conclusion with relatively light casualties on one or both sides. I don’t believe that it is terribly important to find a quantitative reason for such differences, mainly because I don’t think there is any quantitative reason. The differences are usually due to such things as the general circumstances existing when the battles are fought, the personalities of the commanders, and the natures of the missions or objectives of one or both of the hostile forces, and the interactions of these personalities and missions.

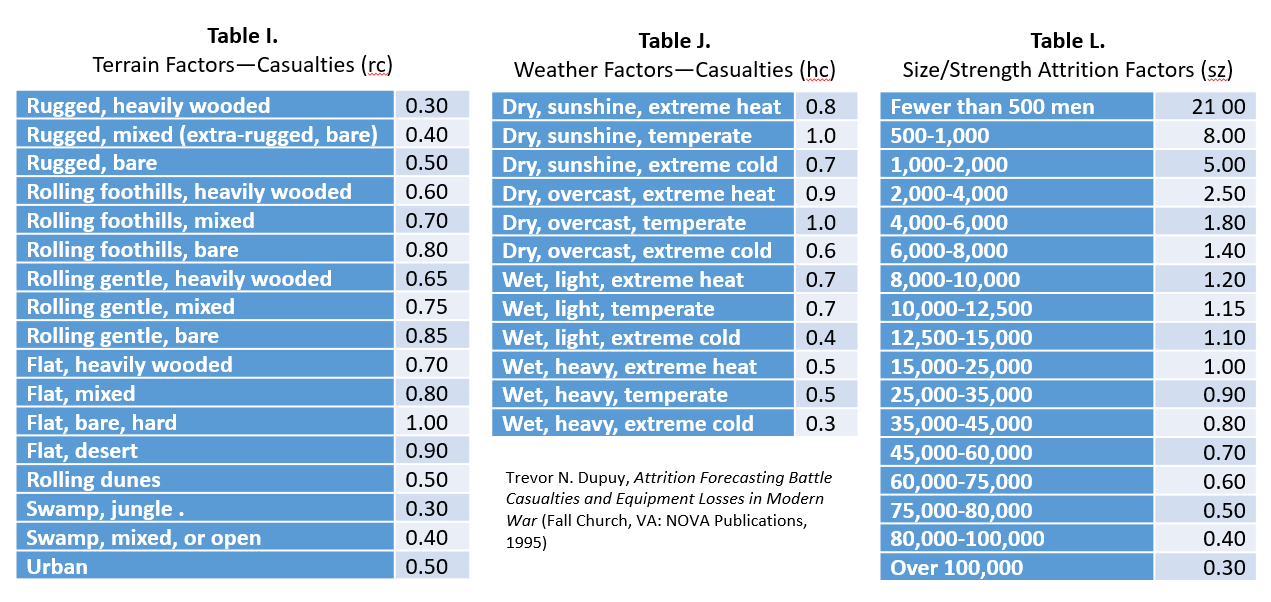

From my standpoint the principal reason for trying to quantify the intensity of a battle is for purposes of comparative analysis. Just because casualties are relatively low on one or both sides does not necessarily mean that the battle was not intensive. And if the casualty rates are misinterpreted, then the analysis of the outcome can be distorted. For instance, a battle fought on a flat plain between two military forces will almost invariably have higher casualty rates for both sides than will a battle between those same two forces in mountainous terrain. A battle between those two forces in a heavy downpour, or in cold, wintry weather, will have lower casualties than when the forces are opposed to each other, under otherwise identical circumstances, in good weather. Casualty rates for small forces in a given set of circumstances are invariably higher than the rates for larger forces under otherwise identical circumstances.

If all of these things are taken into consideration, then it is possible to assess combat intensity fairly consistently. The formula I use is as follows:

CI = CR / (sz’ x rc x hc)

When: CI = Combat Intensity Measure

CR = Casualty rate in percent per day

sz’ = Square root of sz, a factor reflecting the effect of size upon casualty rates, derived from historical experience

rc = The effect of terrain on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

hc = The effect of weather on casualty rates, derived from historical experience

I then (somewhat arbitrarily) identify seven levels of intensity:

0.00 to 0.49 Very low intensity (1)

0.50 to 0.99 Low intensity (56)

1.00 to 1.99 Normal intensity (213)

2.00 to 2.99 High intensity (101)

3.00 to 3.99 Very high intensity (30)

4.00 to 5.00 Extremely high intensity (17)

Over 5.00 Catastrophic outcome (20)

The numbers in parentheses show the distribution of intensity on each side in 219 battles in DMSi’s QJM data base. The catastrophic battles include: the Russians in the Battles of Tannenberg and Gorlice Tarnow on the Eastern Front in World War I; the Russians on the first day of the Battle of Kursk in July 1943; a British defeat in Malaya in December, 1941; and 16 Japanese defeats on Okinawa. Each of these catastrophic instances, quantitatively identified, is consistent with a qualitative assessment of the outcome.

[UPDATE]

As Clinton Reilly pointed out in the comments, this works better when the equation variables are provided. These are from Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Fall Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 146, 147, 149.

Where can the factors for sz, rc and hc be found?

Good question. Let me add them.

Hi Shawn, I had a question regarding this post and how it relates to the material in Col. Dupuy’s “Attrition: forecasting battle casualties and equipment losses in modern war.” Above, you show CR to be proportional to the square root of the size factor and combat intensity, while Eq. 1 on pg. 105 of “Attrition…” states CR is proportional to the size factor and does not include a combat intensity term. I’m interested in calculating CR as a function of unit size and was hoping you could help clarify the two approaches.

Thanks very much!

The equation above is a simple methodology Trevor Dupuy developed to calculate a measurement of combat intensity. It is not a method for calculating casualties.

The equation you cite from page 105 of Dupuy’s Attrition is his revised method for calculating average daily personnel casualties. As you mention, it does not include a factor for intensity. If you are employing his methodology to calculate casualty rates, this is the equation to use.

Dupuy used the same size/strength factors in both equations (Table L above) but termed the factor “sz” in the intensity equation, but changed it to “tz” in the casualty equation. I can’t explain the change in nomenclature but the factors are the same.

Does this answer you question?

Cheers,

–Shawn

Hi Shawn, I had a question regarding this post and how it relates to the material in Col. Dupuy’s “Attrition: forecasting battle casualties and equipment losses in modern war.” Above, you show CR to be proportional to the square root of the size factor and combat intensity, while Eq. 1 on pg. 105 of “Attrition…” states CR is proportional to the size factor and does not include a combat intensity term. I’m interested in estimating CR as a function of unit size, so was hoping you could provide some clarity on the two approaches.

Thanks very much!

It does — thanks again!

Let me just add to this discussion a little bit:

1. Intensity: In the TNDM there are three different types of attacks “Attack (normal)”, “Attack (Main Effort)” and “Attack (Secondary).” They do produce different levels of casualties and indicate differing levels of intensity.

There was also a modification made to the model after 1995 to address “casualty insensitive” systems (i.e. what is the casualty effects of facing the Japanese in WWII).

2. The unit size versus attrition rate tables (page 149 in Attrition) are extremely important. Battalion-level casualty rates are at a different order of magnitude (as far as % loss per day) than division-level casualty rates. We have seen studies and modeling efforts that bounce between division-level and battalion-level data without understanding the differences.