In his new book, On Tactics: A Theory of Victory in Battle, Brett Friedman wrote:

[The] lack of strategic education has produced a United States military adrift. A cottage industry of shallow military thought attached itself to the Department of Defense like a parasite, selling “new” concepts that ranged from the specious (such as the RMA and effects-based operations), to the banal (like “hybrid” and “asymmetric” warfare), to the nonsensical (like 4th Generation Warfare and Gray Zone/Wars). An American officer corps, bereft of a solid understanding of strategic theory, seizes on concept after concept, seeking the next shiny silver bullet that it can fire to kill the specter of strategic disarray.

The U.S. military establishment’s general disregard and disinterest in theorizing about war and warfare is not new. Trevor Dupuy was also critical of the American approach to thinking about theory, especially its superficial appreciation for the value of military history. As he wrote in Understanding War: History and Theory of Combat (1987):

In general, and with only a few significant exceptions, until very recently American military theorists have shown little interest in the concept of a comprehensive theory or science of combat. While most Americans who think about such things are strong believers in the application of science to war, they seem not to believe, paradoxically, that waging war can be scientific, but that it is an art rather than a science. Even scientists concerned with and involved in military affairs, who perhaps overemphasize the role of science in war, also tend to believe that war is a random process conducted by unpredictable human beings, and thus not capable of being fitted into a scientific theoretical structure. [p. 51]

Like Friedman, Dupuy placed a good deal of the blame for this on the way U.S. military officers are instructed. He saw a distinct difference in the approach taken in the U.S. versus the way it was used by the (then) Soviet Union. In a 1989 conference paper, he contended that:

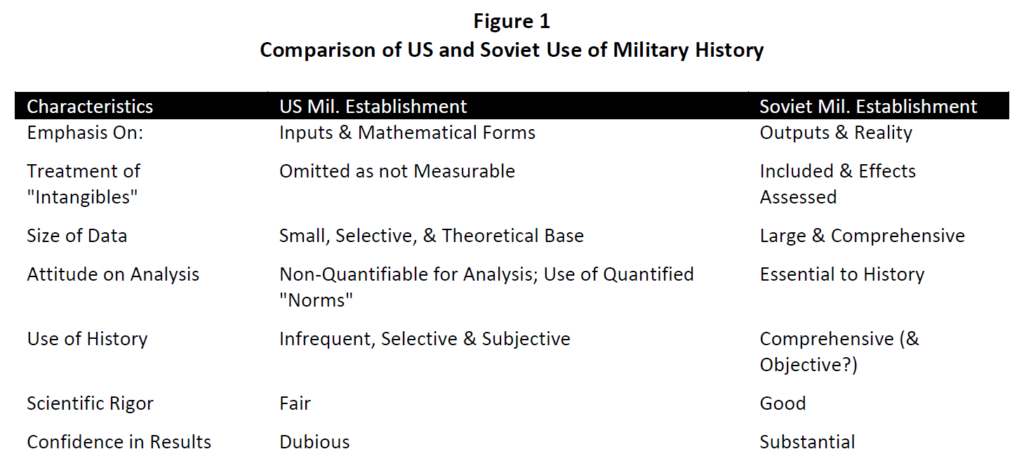

The United States Armed Forces pay lip service to the importance of military history. Officers are urged to read military history, but given little guidance on how military history can be really useful to them. The fundamental difference between the Soviet approach and the American approach, as I see it, is that the American officer is invited (but not really encouraged) to be a military history dilettante. The Soviets seriously study, and use military history. Figure 1 summarizes the differences in approaches of the U.S. and the Soviet armed forces to military history analysis.

Dupuy devoted an entire chapter of Understanding War to the Soviet scientific approach to the study and application of warfare. There was a time when the mention of Soviet/Russian military theory would have produced patronizing smirks from American commentators. In truth, Russian military theorizing has a long and robust tradition; much deeper than its American counterpart. Given the recent success Russia has had in leveraging its national security capabilities to influence favorable geopolitical outcomes, it might be that those theories are useful after all. One need not subscribe to the Soviet scientific approach to warfare to acknowledge the value of a scientific approach to studying warfare.

Dupuy devoted an entire chapter of Understanding War to the Soviet scientific approach to the study and application of warfare. There was a time when the mention of Soviet/Russian military theory would have produced patronizing smirks from American commentators. In truth, Russian military theorizing has a long and robust tradition; much deeper than its American counterpart. Given the recent success Russia has had in leveraging its national security capabilities to influence favorable geopolitical outcomes, it might be that those theories are useful after all. One need not subscribe to the Soviet scientific approach to warfare to acknowledge the value of a scientific approach to studying warfare.

I recall during the last decade of the Cold War (I was serving as a Navy officer) that we used to take a certain amount of pride in comparing our use of doctrine to the Soviets.

I suspect that we were only half kidding when claiming that our Soviet opponents 1) knew our doctrine better than we did and 2) expected that we would follow it.

Their supposed confusion would then be to our great advantage. Now that I’m a little older, I’m just as happy we didn’t test that theory in practice.

>Now that I’m a little older, I’m just as happy we didn’t test that theory in practice.

Roger that.

The link between doctrine and battlefield performance seems indistinct, shall we say. What a force’s doctrine says it should do and what it actually does can be two different things, as you point out. The best doctrine, in my opinion, offers useful ways to think about problems on the battlefield, as opposed to what to think.