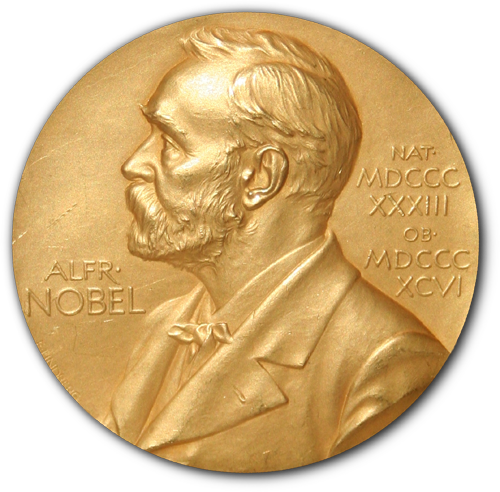

It is really hard to find a more distinguished award than the Nobel awards, created by Alfed Nobel, the Swedish “merchant of death” that invented dynamite and owned Bofors. But there have been a few prizes awarded that are a little odd to say the least. Earlier this month they awarded the Nobel peace prize to Juan Manuel Santos, for negotiating a peace agreement to end the 52 year war between the government of Colombia and the rebel group Fuerza Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC). But five days before the announcement of the prize, the peace deal was rejected by a referendum of Colombian voters. So, peace prize awarded, but no peace.

Just in case the Colombian War has not been on your horizon, not only is it the longest running hot conflict in the world, but it has resulted in the deaths of over 200,000 people. This makes it the second bloodiest war ever in the Western Hemisphere, behind the U.S. Civil War (1861-65) and ahead of the Chaco War (1932-1935).

The war has always operated at a fairly low level. The bloodiest year for the counterinsurgency forces was in 2002 with 1,207 deaths and an estimated 1,817 insurgent deaths. By 2005 these figures had dropped to 143 and 63 respectively. The peak U.S. involvement was in 2002 with 224 advisors. These figures are drawn from our Dupuy Insurgency Spread Sheets (DISS). We never assembled a total figure of deaths from the war so cannot confirm the often used figure of over 200,000 killed, but starting in 1988, the number of homicides in Colombia exceed 20,000 a year, and they were less than 10,000 a year only five years earlier. The war peaked in 2002 and is much, much quieter now.

There have been other strange prizes awarded over the years, like President Obama getting awarded one in 2009, when all he had done to date was get elected nine months earlier. There was a prize awarded in 1973 to Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho for the Paris agreement that brought a ceasefire in the Vietnam War. Le Duc Tho refused to accept the award. The war continued for another two years after the prize, culminating with North Vietnam overrunning South Vietnam. Certainly it was peace at that point, but hardly in the spirit of the prize.

There is one Nobel prize awarded recently that was not odd, this was the literature prize for Bob Dylan. About time! There is no question that Bob Dylan was the single most influential lyricist (and therefore poet) in world in the last 50 years. Before Bob Dylan, song lyrics were basically “she loves you, yea, yea, yea.” After Dylan, there wasn’t a whole lot of subjects not being addressed. Dylan came from a rich American folk and blues tradition very much developed by Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and Pete Seeger. He embraced it, enhanced it, and left an indelible mark on popular music. Just as Homer originally recited his poetic narratives to music, many modern poets are singers and songwriters. This prize just recognizes that obvious, but sometimes overlooked point. People don’t read or write a lot of poetry these days, but they do listen to a lot of music and lyrics. These lyrics are often bad poetry, but not all of them. Some published authors and poets have become song writers (Leonard Cohen and Rod McKuen come to mind, for example). They did not cease to be poets when they became song writers. Even the name of this blog is drawn from a “popular song,” just to drive home the point. Modern poetry often includes a backbeat, be it NWA or Bob Dylan.

A link to the lyrics of My Back Pages: My Back Pages

Last verse: