As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of what potential conflicts in the near future might be like, they see the distinct potential for large tank battles. Will technological advances change the character of armored warfare? Perhaps, but it seems more likely that the next big tank battles – if they occur – will likely resemble those from the past.

As the U.S. Army and the national security community seek a sense of what potential conflicts in the near future might be like, they see the distinct potential for large tank battles. Will technological advances change the character of armored warfare? Perhaps, but it seems more likely that the next big tank battles – if they occur – will likely resemble those from the past.

One aspect of future battle of great interest to military planners is probably going to tank loss rates in combat. In a previous post, I looked at the analysis done by Trevor Dupuy on the relationship between tank and personnel losses in the U.S. experience during World War II. Today, I will take a look at his analysis of historical tank loss rates.

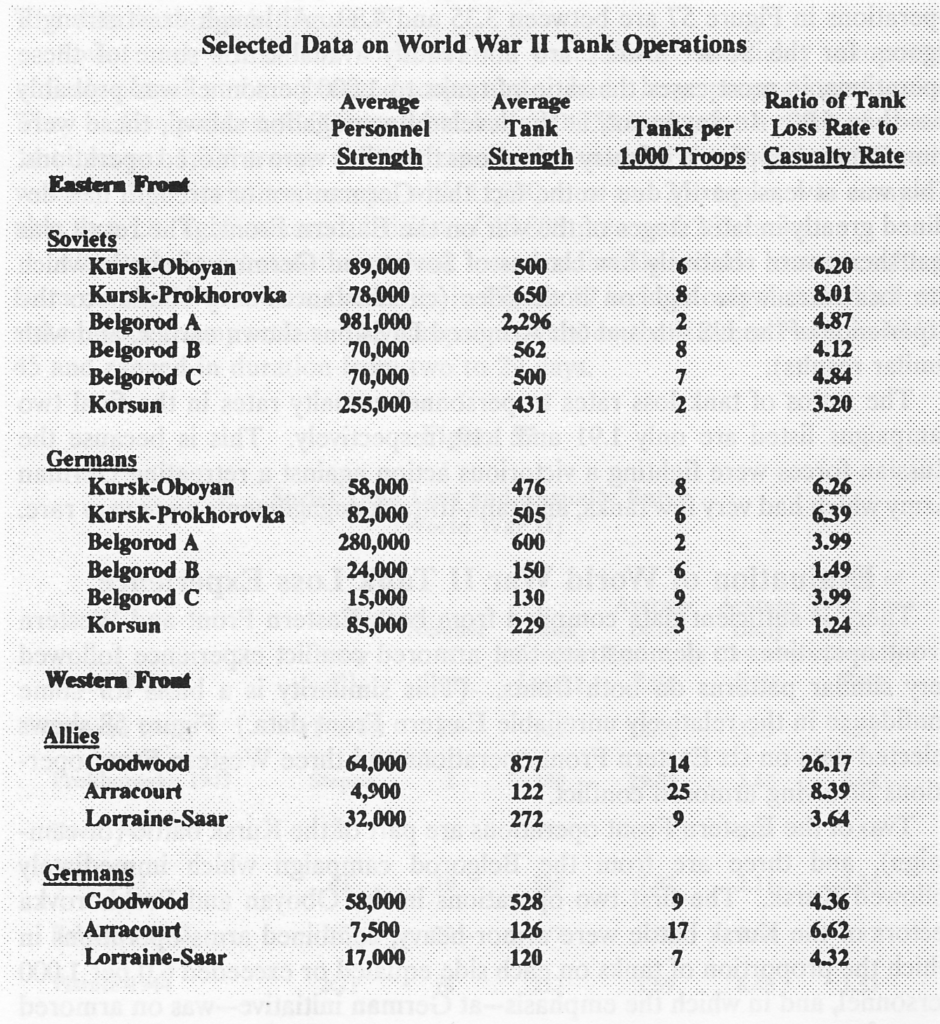

In general, Dupuy identified that a proportional relationship exists between personnel casualty rates in combat and losses in tanks, guns, trucks, and other equipment. (His combat attrition verities are discussed here.) Looking at World War II division and corps-level combat engagement data in 1943-1944 between U.S., British and German forces in the west, and German and Soviet forces in the east, Dupuy found similar patterns in tank loss rates.

In combat between two division/corps-sized, armor-heavy forces, Dupuy found that the tank loss rates were likely to be between five to seven times the personnel casualty rate for the winning side, and seven to 10 for the losing side. Additionally, defending units suffered lower loss rates than attackers; if an attacking force suffered a tank losses seven times the personnel rate, the defending forces tank losses would be around five times.

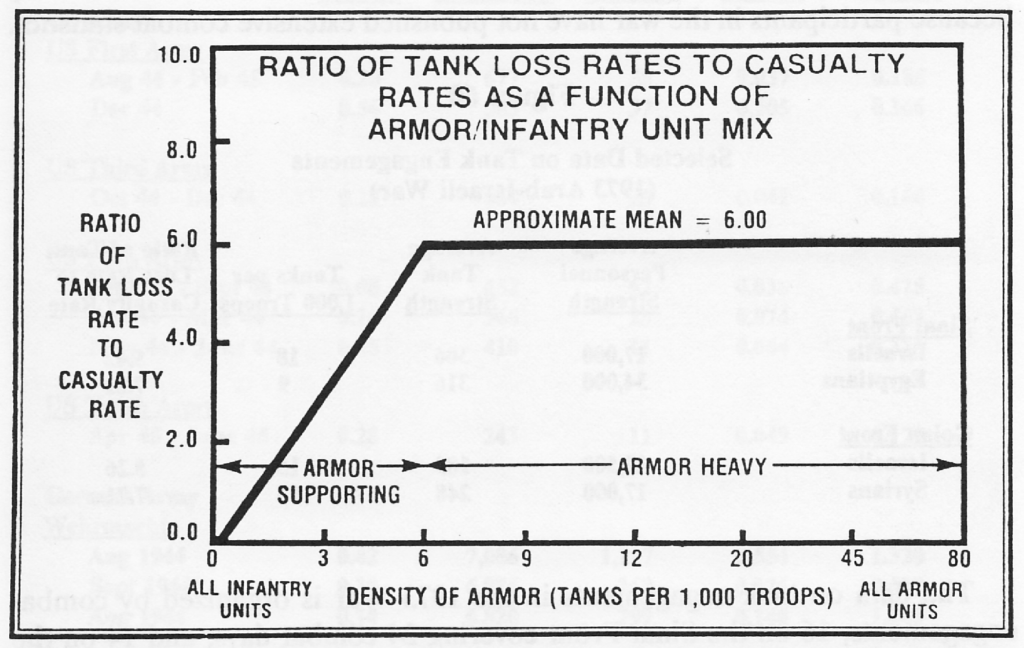

Dupuy also discovered the ratio of tank to personnel losses appeared to be a function of the proportion of tanks to infantry in a combat force. Units with fewer than six tanks per 1,000 troops could be considered armor supporting, while those with a density of more than six tanks per 1,000 troops were armor-heavy. Armor supporting units suffered lower tank casualty rates than armor heavy units.

Dupuy looked at tank loss rates in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and found that they were consistent with World War II experience.

What does this tell us about possible tank losses in future combat? That is a very good question. One guess that is reasonably certain is that future tank battles will probably not involve forces of World War II division or corps size. The opposing forces will be brigade combat teams, or more likely, battalion-sized elements.

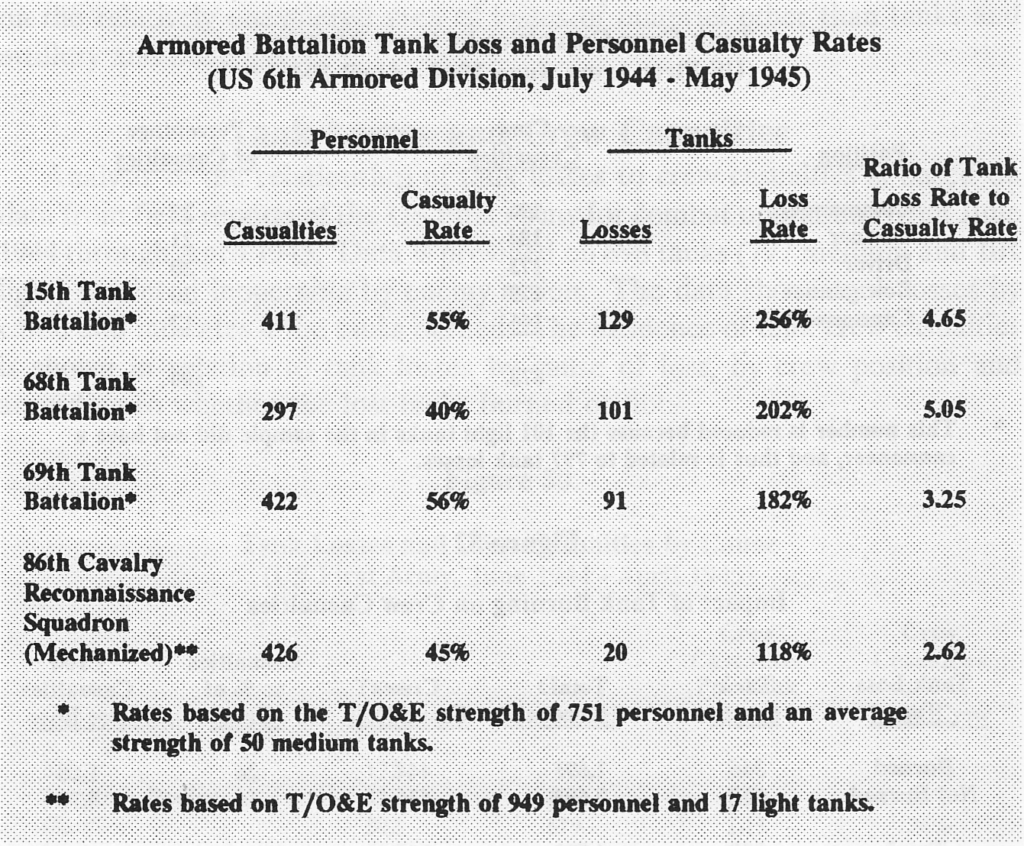

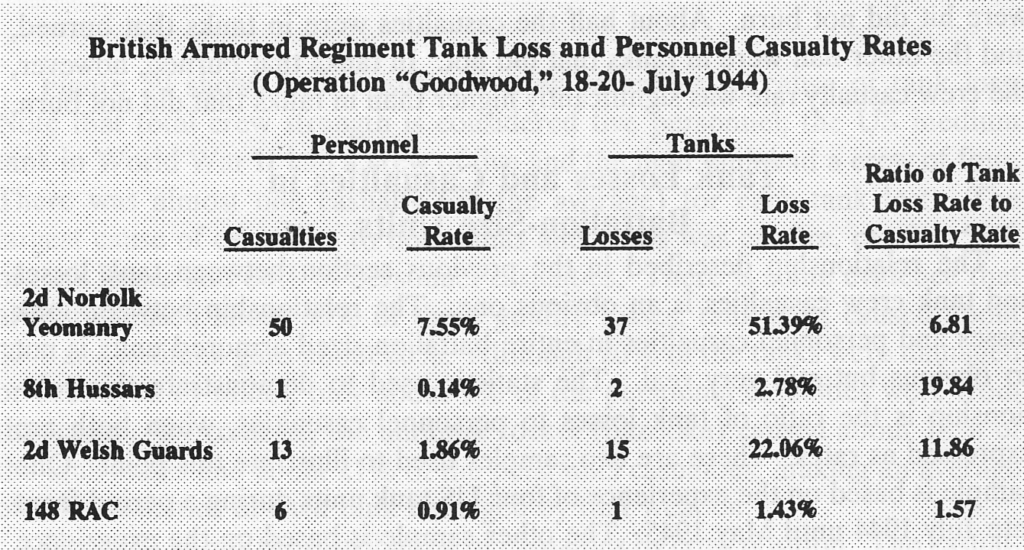

Dupuy did not have as much data on tank combat at this level, and what he did have indicated a great deal more variability in loss rates. Examples of this can be found in the tables below.

These data points showed some consistency, with a mean of 6.96 and a standard deviation of 6.10, which is comparable to that for division/corps loss rates. Personnel casualty rates are higher and much more variable than those at the division level, however. Dupuy stated that more research was necessary to establish a higher degree of confidence and relevance of the apparent battalion tank loss ratio. So one potentially fruitful area of research with regard to near future combat could very well be a renewed focus on historical experience.

NOTES

Trevor N. Dupuy, Attrition: Forecasting Battle Casualties and Equipment Losses in Modern War (Falls Church, VA: NOVA Publications, 1995), pp. 41-43; 81-90; 102-103

Can you advise on the units listed for Goodwood please. 2nd Norfolk Yeomanry, do you mean the 2nd Northamptonshire Yeomanry (reconnaissance). I asked because the only Norfolk Yeomanry unit I can identify is 65th Anti Tank Reg Norfolk Yeomanry associated with 7 Armour Division, The 8 King’s Royal Irish Hussars (reconnaissance), 148th Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps 33 Armoured Brigade and 2nd Battalion, Welsh Guards (Armoured reconnaissance) are all associated with the order of battle.

So questions, one, does potentially 3 of the 4 units as reconnaissance, impact the the analysis and secondly given General Dempsey strategy was to fight with Tanks only, basically not following armour warfare procedures because he had loads of them so holding back the infantry to protect them. What impact does that have given tactical the objectives were not achieved, but strategically it was a significant success in eliminating the German reserves, for the cobra breakthrough.

We know from resent analysis the numbers of kill claims by the German units are questionable. When, comparison are undertaken by an apple to apple basis, the total of written off tanks for Operation Goodwood is about 150 British tanks compared to the 83 German tanks and assault guns written off so 1.8:1. So far from the disaster which the narrative usually described, originally taken from German kill claims (now discredited by the latest research) which were often considered accurate because they match the British knocked out numbers.

Hi David,

Per the citation in Attrition on page 135, Trevor Dupuy cited his source for the British Goodwood regimental tank losses as: Department of the Scientific Advisor to the Army Council, Military Operational Research Unit, Report No. 23, Battle Study: Operation “Goodwood,” October 1946. I will have to ask Chris Lawrence if there is a copy of this in the TDI files.

UPDATE: It appears some kind soul actually posted a transcription of the report online in 2011: http://ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/battle-study-operation-goodwood.35848/

The tank losses are listed on the second page.

>does potentially 3 of the 4 units as reconnaissance, impact the the analysis

I would not think so. Dupuy was looking at the tank casualty loss rates relative to 1) the proportion of tanks to infantry in the unit as a whole; and 2) the variability of tank loss rates at the brigade/regiment/battalion level. The British Goodwood losses appear to be an outlier with respect to Dupuy’s conclusions about tank-to-infantry ratios. They do illustrate the variability in tank loss rates below the division level, although as mentioned in the post, this phenomenon needs to be looked at in more detail.

Dupuy did not do any battle analysis of the Goodwood battle, but he did suggest on pages 84-85 in Attrition that the British loss rates were probably affected by two factors. First, the British lost the battle. Personnel and material loss rates for losing forces are higher than winners, regardless of posture. The second factor was the high tank-to-infantry ratio employed by the British in the attack (about 14 tanks per 1,000 infantry). His analysis suggested that in combined arms combat, the ratio of tank loss rates to personnel rates increases proportionally, at least up to a certain point.

>We know from resent analysis the numbers of kill claims by the German units are questionable.

Chris has also noted this before, but I am not sure how this relates to Dupuy’s analysis. The losses cited in his tables were taken from statements of losses by the participants, not estimates of kills.

I hope this addresses your questions.

Cheers,

–Shawn

Shawn

Hi, yes thank you very informative. I obtained access to the WW2talk blog, which was very useful, particularly around the casualties for infantry and tank crews. It is known Dempsey’s strategy, was to protect his infantry at the expense of his tanks. WO 162/16 details the actual casualties with WO 205/152, details the forecast for 21st Army Group, whilst overall casualties were well within expectations, the infantry was a major concern, the July forecast was around 9100 whilst actually was 22,000. There was a lot of pressure on Montgomery from the U.K. and Canadian governments to limit casualties because of the WW1 experience.

You may find this of interest a PDF dissertation by Steven Hart, on Montgomery and 21 Army Group, with analysis of the casualty rates. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/2927568/283396.pdf

David

Very interesting. That would explain the unusual British tank-to-infantry ratio for Goodwood. This would make an interesting case study with regard to combined arms tactics/operations and personnel/material loss rates.

Shawn

Yes, I think that would be a worthwhile exercise. General Alexander was under the same pressure in Italy, again the U.K but also New Zealand and South Africa governments. The losses during WW1 weighed heavy on the all the Commonwealth senior officers so must have influenced how they conducted combat. It is driving a review of WW 2, by historians in light of resent experiences.

OK, now I am curious about the influence the concern about casualties had on British military performance. I quite liked Hart’s PhD thesis (thanks for the link). Do you have more suggestions on this recent historical re-evaluation of British WWII operations?

Shawn

Hi some additional information which may be of interest considering the YouTube presentations.

Dr Jonathan Fennell is a Senior Lecturer in Defence Studies at King’s College London. He joined the Defence Studies Department in 2009. His presentation is worth watching considering the analysis of the Italian campaign and the morale difficulty around the New Zealand and South African armoured divisions. Qualitatively, I think it aligns with Christopher’s work on the combat performance.

He also refers to Steven Harts Phd dissertation.

Kings College hold the papers of a number of WW 2 Generals plus Liddell Hart.

Kr

David.

David, thank you very much for the references. They will be very interesting reading.

I wrote about Jonathan Fennell’s work before; it is quite good: https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/2016/05/05/human-factors-in-warfare-measuring-morale/

You might also find this interesting: https://dupuyinstitute.dreamhosters.com/2017/11/21/command-and-combat-effectiveness-the-case-of-the-british-51st-highland-division/

There is another analysis of Goodwood you might find of interest in Stephen Biddle’s Military Power. It is pretty good, but his conclusions about it probably need to be revisited in light of the new historiography. He wants to take Goodwood as representative, but it looks like that battle is more of a tactical anomaly. The question is, did the British repeat the tank-heavy approach to limiting infantry casualties again after Goodwood, or did the heavy tank losses sustained there deter them from trying it again? For example, what was the tank-to-infantry ratio for the XXX Corps attack in Market-Garden?

UK overall losses did not reach WW1 levels because they engaged a smaller fraction of the German Army.

The losses per division in both conflicts were approximately the same: In 1918 the BEF suffered 852,861 casualties, that is 70,000 casualties monthly or 1,100 per Division. In 1944-45 you have 191,219 casualties, 17,000 monthly or 1,000 per division.

Casualties were already lowered, since the Soviets were absorbing most of the damage.

Other than that, it does not seem that Montgomery managed to keep them low. I would even argue that they still had the 1940 campaign in mind, the fear of operational failure.

Shawn and Stiltzkin

Hi

You may find of interest

1, British Armour in the Normandy Campaign 1944, professor John Buckley university of Wolverhampton, he does go into morale and motivation.

On YouTube he is associated with Defence Research, which have a few of his presentations to U.K. defence establishments

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLYJk_eJuuq2vK_KVmVBR-tFUnGpZBNPCJ

The work in progress, presentation has been published by Yale university press

Monty’s men : the British Army and the liberation of Europe, 1944-5.

I have yet to obtain a copy, the academic reviews highly recommend.

2, The Armoured Campaign in Normandy June-August 1944 Stephen Napier, this exceptionally well researched, it was recommended by Christian Ankerstjerne, who recommended Mythics & Statistics

Given the interest in Italy, these may be of interest, by New Zealand Phd students. General Freyberg lead the New Zealand forces and received instructions from the Prime Minister of New Zealand to limit casualties.

https://mro.massey.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10179/9869/02_whole.pdf

‘As a matter of fact I’ve just about had enough’;1 Battle weariness and the 2nd New Zealand Division during the Italian Campaign, 1943-45.

https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a463140.pdf

THE FALL OF CRETE 1941: WAS FREYBERG CULPABLE?

You may find the 1946 document “Notes on the Operations of 21 Army Group. 6 June 1944 – 5 May 1945” It is available digitally from the Army Command and General Staff College,100 Stimson Ave,Fort Leavenworth,KS,66027.

It covers all operations from landing in Normandy to Hamburg.

Finally this is an interview with Montgomery, it is worth a watch, as an insight to his thinking. https://youtu.be/H1dz3pqbRaw

David

I think its possible for all of these to be true, for the Soviet Army to have gutted the Wehrmacht in battle, for the British to have suffered fewer total battle casualties in WWII than WWI, and for the British government to be more politically sensitive to these losses in 1944-45 than in 1918. Without having yet read the new British historiography, I would agree that it might be difficult to support the argument that casualty sensitivity was a greater factor in British operational performance than avoiding failure. It is one thing to want to limit casualties in combat, but it is another to actually accomplish it. I am curious to see the supporting analysis before drawing a conclusion.

The argument applies to all sides: Germany never expected to end up in a war of attrition on the EF, yet WW1 kicked in again, this time in the East.

In 1944-45, the BEF faced on average, 15-20 Divisions. In 1918, over 60. That explains the casualty differential. 70,000/3,5 = 20,000.

In 1940, the BEF suffered 68,920 (10th may to evacuation) operational losses, or 2,760 casualties daily (700 in 1944), 1,700 casualties per Division.

Juxtaposed, just a crude calculation: The Soviets absorbed (1944), 40,000 casualties per Division (similar period). That would be 8,000 casualties “normalized” to Soviet levels (over 7x the total number of Divisions engaged). Adjusted for circumstantial factors and posture, yields 847,000 (for 11 months). Compare with 1918: 852,861 (12 months).

Quite late to the party here, but have long held the work of the Dupuy Institute in high esteem. First editions of “Numbers, Prediction and War” and “Atrittion” remain still in my reference library; they have stood the test of time very well.

Re British sensitivities about casualties, by late 1917 the British Army on the Western Front had slightly more personnel serving with the Artillery Arm than in the Infantry. In WW2, according to Michael Carver (“Alamein” IIRC), by 1942 the British Army was already disbanding formations in order to keep up with personnel shortages.

Any opinions yet on this new two volume history, “Bloody Verrieres”? (Volume 1 has just come out).