[NOTE: This post has been edited to more accurately characterize Trevor Dupuy’s public comments on TNDA’s estimates.]

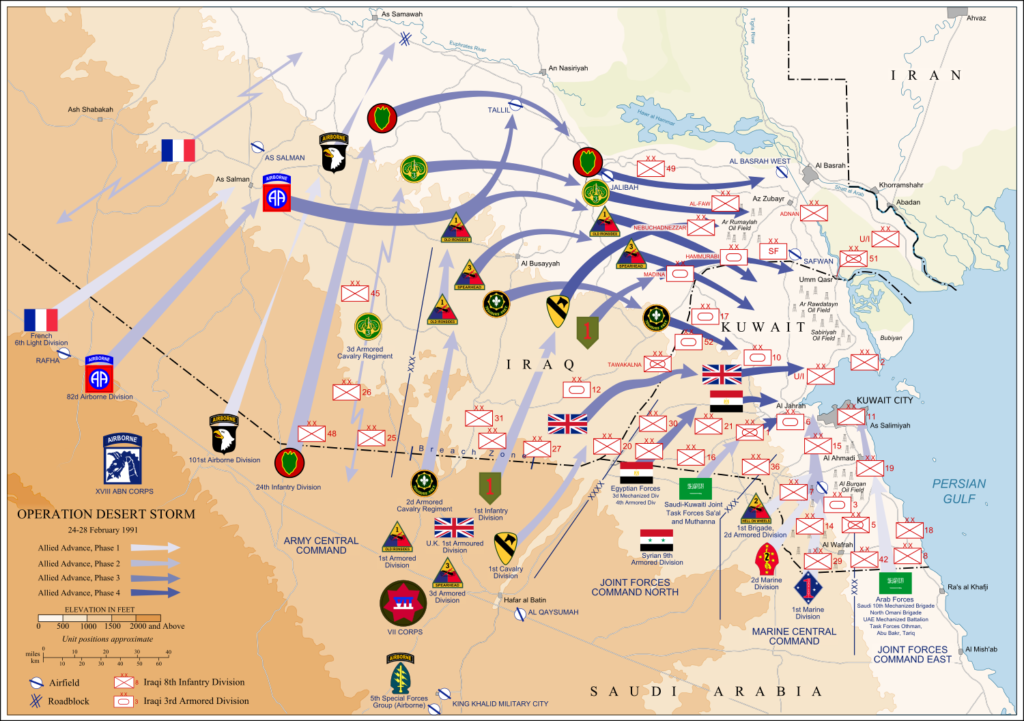

Operation DESERT STORM began on 17 January 1991 with an extended aerial campaign that lasted 38 days. Ground combat operations were initiated on 24 February and concluded after four days and four hours, with U.S. and Coalition forces having routed the Iraqi Army in Kuwait and in position to annihilate surviving elements rapidly retreating northward. According to official accounting, U.S. forces suffered 148 killed in action and 467 wounded in action, for a total of 614 combat casualties. An additional 235 were killed in non-hostile circumstances.[1]

In retrospect, TNDA’s casualty forecasts turned out to be high, with the actual number of casualties falling below the lowest +/- 50% range of estimates. Forecasts, of course, are sensitive to the initial assumptions they are based upon. In public comments made after the air campaign had started but before the ground phase began, Trevor Dupuy forthrightly stated that TNDA’s estimates were likely to be too high.[2]

In a post-mortem on the forecast in March 1991, Dupuy identified three factors which TNDA’s estimates miscalculated:

- an underestimation of the effects of the air campaign on Iraqi ground forces;

- the apparent surprise of Iraqi forces; and

- an underestimation of the combat effectiveness superiority of U.S. and Coalition forces.[3]

There were also factors that influenced the outcome that TNDA could not have known beforehand. Its estimates were based on an Iraqi Army force of 480,000, a figure derived from open source reports available at the time. However, the U.S. Air Force’s 1993 Gulf War Air Power Survey, using intelligence collected from U.S. government sources, calculated that there were only 336,000 Iraqi Army troops in and near Kuwait in January 1991 (out of a nominal 540,000) due to unit undermanning and troops on leave. The extended air campaign led a further 25-30% to desert and inflicted about 10% casualties, leaving only 200,000-220,000 depleted and demoralized Iraqi troops to face the U.S. and Coalition ground offensive.[4].

TNDA also underestimated the number of U.S. and Coalition ground troops, crediting them with a total of 435,000, when the actual number was approximately 540,000.[5] Instead of the Iraqi Army slightly outnumbering its opponents in Kuwait as TNDA approximated (480,000 to 435,000), U.S. and Coalition forces probably possessed a manpower advantage approaching 2 to 1 or more at the outset of the ground campaign.

There were some aspects of TNDA’s estimate that were remarkably accurate. Although no one foresaw the 38-day air campaign or the four-day ground battle, TNDA did come quite close to anticipating the overall duration of 42 days.

DESERT STORM as planned and executed also bore a striking resemblance to TNDA’s recommended course of action. The opening air campaign, followed by the “left hook” into the western desert by armored and airmobile forces, coupled with holding attacks and penetration of the Iraqi lines on the Kuwaiti-Saudi border were much like a combination of TNDA’s “Colorado Springs,” “Leavenworth,” and “Siege” scenarios. The only substantive difference was the absence of border raids and the use of U.S. airborne/airmobile forces to extend the depth of the “left hook” rather than seal off Kuwait from Iraq. The extended air campaign served much the same intent as TNDA’s “Siege” concept. TNDA even anticipated the potential benefit of the unprecedented effectiveness of the DESERT STORM aerial attack.

How effective “Colorado Springs” will be in damaging and destroying the military effectiveness of the Iraqi ground forces is debatable….On the other hand, the circumstances of this operation are different from past efforts of air forces to “go it alone.” The terrain and vegetation (or lack thereof) favor air attacks to an exceptional degree. And the air forces will be operating with weapons of hitherto unsuspected accuracy and effectiveness against fortified targets. Given these new circumstances, and considering recent historical examples in the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli Wars, the possibility that airpower alone can cause such devastation, destruction, and demoralization as to destroy totally the effectiveness of the Iraqi ground forces cannot be ignored. [6]

In actuality, the U.S. Central Command air planners specifically targeted Saddam’s government in the belief that air power alone might force regime change, which would lead the Iraqi Army to withdraw from Kuwait. Another objective of the air campaign was to reduce the effectiveness of the Iraqi Army by 50% before initiating the ground offensive.[7]

Dupuy and his TNDA colleagues did anticipate that a combination of extended siege-like assault on Iraqi forces in Kuwait could enable the execution of a quick ground attack coup de grace with minimized losses.

The potential of success for such an operation, in the wake of both air and ground efforts made to reduce the Iraqi capacity for offensive along the lines of either Operation “Leavenworth’…or the more elaborate and somewhat riskier “RazzleDazzle”…would produce significant results within a short time. In such a case, losses for these follow-on ground operations would almost certainly be lower than if they had been launched shortly after the war began.[8]

Unfortunately, TNDA did not hazard a casualty estimate for a potential “Colorado Springs/ Siege/Leavenworth/RazzleDazzle” combination scenario, a forecast for which might very well have come closer to the actual outcome.

Dupuy took quite a risk in making such a prominently public forecast, opening his theories and methodology to criticism and judgement. In my next post, I will examine how it stacked up with other predictions and estimates made at the time.

NOTES

[1] Nese F. DeBruyne and Anne Leland, “American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics,” (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2 January 2015), pp. 3, 11

[2] Christopher A. Lawrence, America’s Modern Wars: Understanding Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam (Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2015) p. 52

[3] Trevor N. Dupuy, “Report on Pre-War Forecasting For Information and Comment: Accuracy of Pre-Kuwait War Forecasts by T.N. Dupuy and HERO-TNDA,” 18 March, 1991. This was published in the April 1991 edition of the online wargaming “fanzine” Simulations Online. The post-mortem also included a revised TNDM casualty calculation for U.S. forces in the ground war phase, using the revised assumptions, of 70 killed and 417 wounded, for a total of 496 casualties. The details used in this revised calculation were not provided in the post-mortem report, so its veracity cannot be currently assessed.

[4] Thomas A. Keaney and Eliot A. Cohen, Gulf War Airpower Survey Summary Report (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Air Force, 1993), pp. 7, 9-10, 107

[5] Keaney and Cohen, Gulf War Airpower Survey Summary Report, p. 7

[6] Trevor N. Dupuy, Curt Johnson, David L. Bongard, Arnold C. Dupuy, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein: Scenarios and Strategies for the Gulf War (New York: Warner Books, 1991), p. 58

[7] Gulf War Airpower Survey, Vol. I: Planning and Command and Control, Pt. 1 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Air Force, 1993), pp. 157, 162-165

[8] Dupuy, et al, How To Defeat Saddam Hussein, p. 114